Syllabus: GS3/Economy

Context

- Over the last decade, India has built one of the largest skilling ecosystems in the world, yet skilling has not become a first-choice pathway for most young Indians.

About

- The India Skills Report 2025 shows that only about 2% of graduates pursue additional skilling certifications after completing degrees.

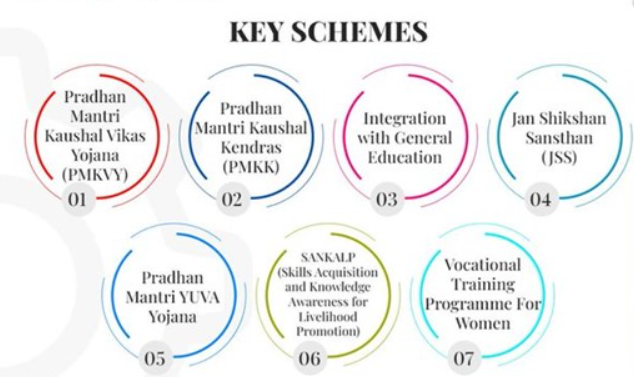

- Between 2015 and 2025, India’s flagship skilling programme, Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana (PMKVY), has trained and certified around 1.40 crore candidates, reflecting serious public investment and policy intent.

- PLFS data show that wage gains from vocational training are modest and inconsistent, offering limited recognition for certified skills and little visible improvement in quality of life.

- In contrast, vocational participation exceeds 70% in Germany and Japan and crosses 90% in South Korea (OECD).

Reasons for not Preferring Skilling

- Legitimacy of Degrees: Degrees indicate long-term mobility, social recognition, and economic credibility.

- Skilling does not lead to recognised qualifications and progressive employment thus, participation becomes unaspirational.

- Limited reliance on public certifications: Most employers do not treat government skilling certifications as credible hiring benchmarks, preferring internal training systems, referrals, or private platforms.

- Uneven impact of apprenticeships: While the National Apprenticeship Promotion Scheme (NAPS) has expanded industry participation, benefits are concentrated among large firms, with MSMEs remaining marginal.

- Demand–supply mismatch persists: Skilling remains something industry consumes rather than co-designs, resulting in training that often lags behind evolving labour-market needs.

Key Challenges in the Ecosystem

- Sector skill councils: SSCs are industry-led bodies under the National Skill Development Corporation (NSDC), mandated to define skill standards, ensure industry relevance, and enhance employability; however, this mandate has not been fully realised.

- Certifications from AWS, Google Cloud, or Microsoft work because the certifier’s credibility is at stake.

- Until SSCs are held accountable for employability, certification will remain symbolic rather than economic.

- Responsibility is Fragmented: Unlike Higher Education or Technical Institutions where reputational risk enforces accountability, the skilling system diffuses responsibility without consequence which has eroded trust.

- Weak industry role in curriculum design: Industry faces neither strong incentives nor binding obligations to participate in curriculum development, certification standards, or assessment frameworks.

- Without deeper industry ownership, skilling programmes struggle to remain relevant, credible, and scalable.

Way Ahead

- Workplace-embedded skilling as a fast lever: Expanding NAPS and deepening industry integration can rapidly improve job readiness by shifting skill acquisition into real work environments.

- Integrating skills with formal education: Embedding skills within degree and diploma pathways enhances credibility, aspiration, and labour-market alignment.

- Industry as co-owner, not end-user: Treating industry as a co-designer and co-owner of skilling programmes ensures curriculum relevance and hiring alignment.

- Outcome accountability for SSCs: Making Sector Skill Councils answerable for placement and employability outcomes can restore certification credibility.

Conclusion

- India’s Gross Enrolment Ratio (GER) stands at 28%, but the National Education Policy 2020 aims for it to touch the 50% mark by 2035.

- For skilling to scale credibly and inclusively, it must be integrated with formal education systems, not run parallel to them.

- Industry-linked, education-embedded skill is essential for converting India’s demographic strength into sustained economic growth and productivity gains.

Source: TH

Previous article

News In Short 06-01-2026

Next article

CAG Flags States’ Fiscal Stress