Syllabus: GS3/ Economy

In Context

- A recent report by Crisil projects revenue growth of 7–9% in FY26 for India’s 18 largest states (covering 90% of GSDP), slightly up from 6.6% in FY25. This signals a degree of stability, with revenues expected to touch ₹40 trillion, aided by robust GST collections and excise on liquor.

- However, beneath the surface lies a concerning reality like rising debt burdens, increased dependence on the Union, and narrowing state autonomy.

Revenue Composition of States

- State revenues comprise:

- Own tax revenue (OTR): GST, state excise, stamps & registration.

- Own non-tax revenue (ONTR): User charges, interest receipts, dividends.

- Transfers from the Centre: Share in Union taxes + grants-in-aid.

- Key Trends (as per PRS Legislative Research and Crisil):

- In 2024–25, 42% of states’ revenues were estimated to come from the Centre.

- Central transfers accounted for 23–30% of state revenues (2015–25), up from 20–24% (2000s).

- 65–70% of states’ non-tax revenue was from Union grants, indicating dependency.

- OTR and ONTR together formed only 58% of total revenue receipts.

This reflects a decline in fiscal autonomy, making state budgets vulnerable to Central policy and political shifts.

Debt and Fiscal Deficit Trends

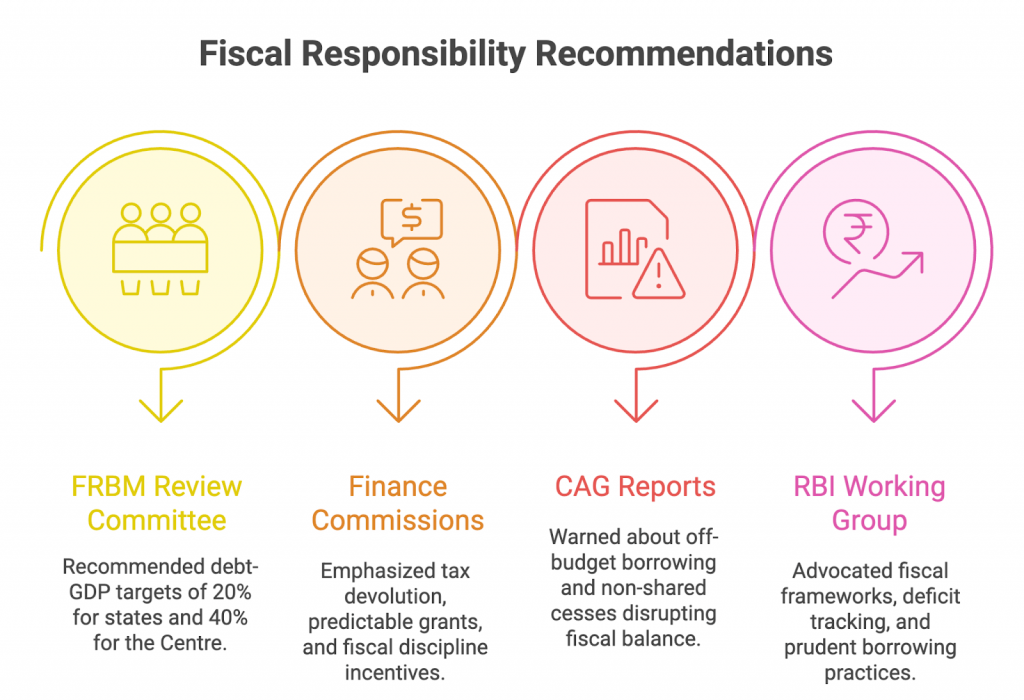

- The aggregate debt-to-GSDP ratio of states stood at 28.5% in 2023-24, breaching the FRBM target of 20%, with 12 states exceeding 35% debt-GSDP, raising concerns about sustainability.

- Despite higher debt burdens, states have improved fiscal discipline by keeping gross fiscal deficits around 2.7% of GDP (2004–24 average) and largely adhering to the FRBM-mandated 3% of GSDP deficit ceiling.

- This indicates tight expenditure control but risks underinvestment in critical areas like health, education, and infrastructure.

Structural and Institutional Challenges

- Revenue growth below decade average (7-9% vs 10%) due to stagnation in petroleum taxes and GST compliance issues, plus inefficiency in property tax and user charges.

- GST reduced states’ indirect tax autonomy; compensation cess ended in 2022, leaving some states struggling to meet revenues.

- Reliance on cesses and surcharges by Centre has grown from 10% (2011-12) to over 25% (2024), not shared with states, increasing vertical fiscal imbalance and uncertainty in transfers.

- Delays and arbitrary reductions in Finance Commission grants hurt equitable distribution and fiscal planning, especially in poorer states.

Reform Measures and Policy Suggestions

- States: Enhance GST compliance through digital invoicing and fraud detection; modernize property tax and user charge collections; use AI and analytics for tax intelligence; adopt dynamic debt management focusing on capital-link loans.

- Centre: Commit to timely, predictable transfers per Finance Commission recommendations; rationalize cesses and surcharges possibly by capping or sharing; foster cooperative federalism by supporting tailored state-specific fiscal policies rather than imposing uniform mandates.

Conclusion

- The fiscal outlook for states is cautiously optimistic with stabilized revenue growth and improved discipline. However, rising debts, high Central dependence, GST-related revenue limitations, and increasing cesses/surcharges challenge fiscal autonomy and sustainability.

- Addressing structural revenue concerns and refining Centre–State transfer mechanisms are crucial for the long-term robustness of India’s federal fiscal architecture.

| Daily Mains Practice Question [Q] India’s states are witnessing rising debt burdens despite maintaining fiscal discipline. Analyze the reasons behind this trend and evaluate the implications for long-term economic growth and development. |

Source: BS

Previous article

Data Exchanges Can Boost Digital Public Infrastructure