Syllabus: GS2/Social Justice; Governance

Context

- The ‘Juvenile Justice and Children in Conflict with the Law: A Study of Capacity at the Frontlines’, released by the India Justice Report (IJR) revealed alarming gaps in India’s juvenile justice system.

Key Findings of Study

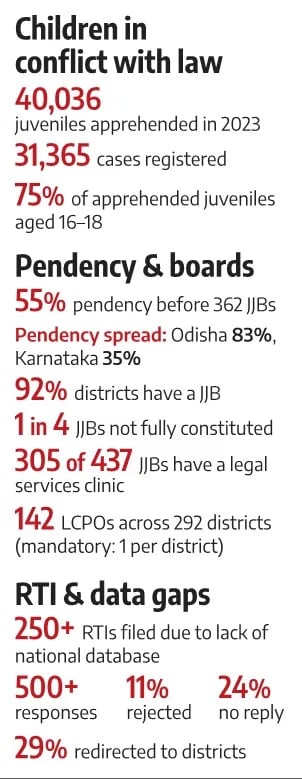

- High Pendency Across Juvenile Justice Boards (JJBs): About 55% of the cases before 362 Juvenile Justice Boards (JJBs) across the country remained pending.

- Pendency rates vary significantly — from 83% in Odisha to 35% in Karnataka, although 92% of India’s 765 districts have constituted JJBs (as on October 2023).

- The findings highlight serious inefficiencies in case management and delivery of justice for Children in Conflict with the Law (CCL).

- Lack of Centralized Data and Transparency: There is no centralized public database for JJBs, unlike the National Judicial Data Grid (NJDG) for regular courts.

- RTI responses from 21 states, filed by IJR, revealed that JJBs had disposed of fewer than half of the 1,00,904 cases registered nationwide.

- Out of 500 RTI responses from 28 states and two Union Territories, 11% were rejected, 24% received no reply, 29% were transferred to district offices, and only 36% were provided by state-level nodal agencies.

- It reflects a weak culture of data sharing and transparency across the system.

- Vacancies and Resource Constraints: The study noted that 24% of JJBs were not fully constituted, and 30% lacked an attached legal services clinic, limiting access to legal aid.

- On average, each JJB was managing 154 pending cases annually, placing immense strain on existing personnel.

- It is attributed to the backlog to staff shortages, inadequate funding, and poor data monitoring, all of which undermine the implementation of the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015.

- Systemic Weaknesses: The IJR study highlights persistent systemic and structural weaknesses, even after a decade of the JJ Act, 2015, that includes:

- Poor inter-agency coordination;

- Absence of integrated data systems;

- Limited oversight and supervision mechanisms;

- Weak accountability structures;

- The decentralized framework intended to deliver child-centric services often suffers from fragmented implementation and lack of standardization across states.

| Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015 – It provides a comprehensive legal framework for the care, protection, development, and rehabilitation of children in need, including those in conflict with the law. – It replaced the earlier 2000 legislation to address emerging challenges in juvenile justice. Two Categories of Children – Children in Conflict with Law (CCL): Those alleged or found to have committed an offence under the law and are below 18 years of age. – Children in Need of Care and Protection (CNCP): Those who are vulnerable or at risk, including orphans, abandoned children, and victims of abuse. Key Features – The JJA allows children aged 16–18 to be tried as adults for heinous crimes, subject to assessment by the Juvenile Justice Boards (JJBs). – It emphasizes reformation and social reintegration through child care institutions, foster care, and adoption. – Amendment in 2021 put greater authority to District Magistrates to ensure effective implementation of the Act, including oversight of Child Welfare Committees (CWCs) and JJBs. Role and Structure of Juvenile Justice Boards (JJBs) – JJBs are quasi-judicial bodies established in every district to handle cases involving children in conflict with the law. – Composition: 1. One Metropolitan Magistrate or Judicial Magistrate First Class (serves as Chairperson); 2. Two social worker members, including at least one woman; – Key Functions: 1. Conduct inquiries and trials for offences committed by juveniles; 2. Assess whether a child aged 16–18 should be tried as an adult for heinous offences; 3. Ensure legal aid, psychological support, and child-friendly procedures during proceedings; 4. Refer children to rehabilitation programs and monitor their progress; – Child-Centric Approach: 1. Proceedings are conducted in a non-adversarial, informal setting; 2. Emphasis on the child’s best interests, privacy, and dignity; 3. Rehabilitation and reintegration prioritized over punitive measures. |

Suggestions Made in Study

- Probation and Rehabilitation Should Be Central: India Justice Report (IJR) emphasized that probation should be the cornerstone of juvenile justice, focusing on rehabilitation rather than punishment.

- According to Crime in India 2023 data, 40,036 juveniles were apprehended in 31,365 cases under the Indian Penal Code and special laws, with three out of four aged between 16 and 18 years — underscoring the need for reformative rather than punitive approaches.

- Fill Vacancies Promptly: Expedite the appointment of social worker members to ensure all JJBs function with the full three-member panel.

- Standardize Training and Capacity Building: Implement regular, structured training for JJB members, police, and probation officers on child rights, trauma-informed care, and the Juvenile Justice Act.

- Improve Infrastructure and Support Services: Ensure JJBs have child-friendly spaces, dedicated courtrooms, and access to counselors, translators, and legal aid providers.

- Strengthen Monitoring and Data Systems: Develop real-time digital dashboards to track case pendency, board composition, and service delivery metrics.

- Enhance Inter-agency Coordination: Foster collaboration between JJBs, Child Welfare Committees (CWCs), District Child Protection Units (DCPUs), and police to streamline rehabilitation and reintegration.

Conclusion

- The IJR study exposes critical gaps in capacity, coordination, and transparency within India’s juvenile justice framework.

- The system will continue to fall short of serving the best interests of children, undermining the very essence of juvenile justice, until a National Data Grid is established and regular data publication becomes mandatory.

Previous article

SC States it cannot Impose Timelines on President and Governors

Next article

India-U.S. Defence Deal