YOJANA June 2025

The following topics are covered in the YOJANA June 2025:

Chapter 1: Operation SINDOOR

Operation SINDOOR was launched by India in May 2025 as a direct response to the Pahalgam terror attack on April 22, 2025, where 26 Indian tourists were brutally killed, with the assailants reportedly segregating victims based on religion.

- The attack was claimed by The Resistance Front, a proxy of Lashkar-e-Taiba.

- In retaliation, India executed Operation SINDOOR — a swift, precise, and non-escalatory military campaign designed to dismantle cross-border terror infrastructure, without provoking a wider conventional war.

Key Achievements and Strategic Outcomes:

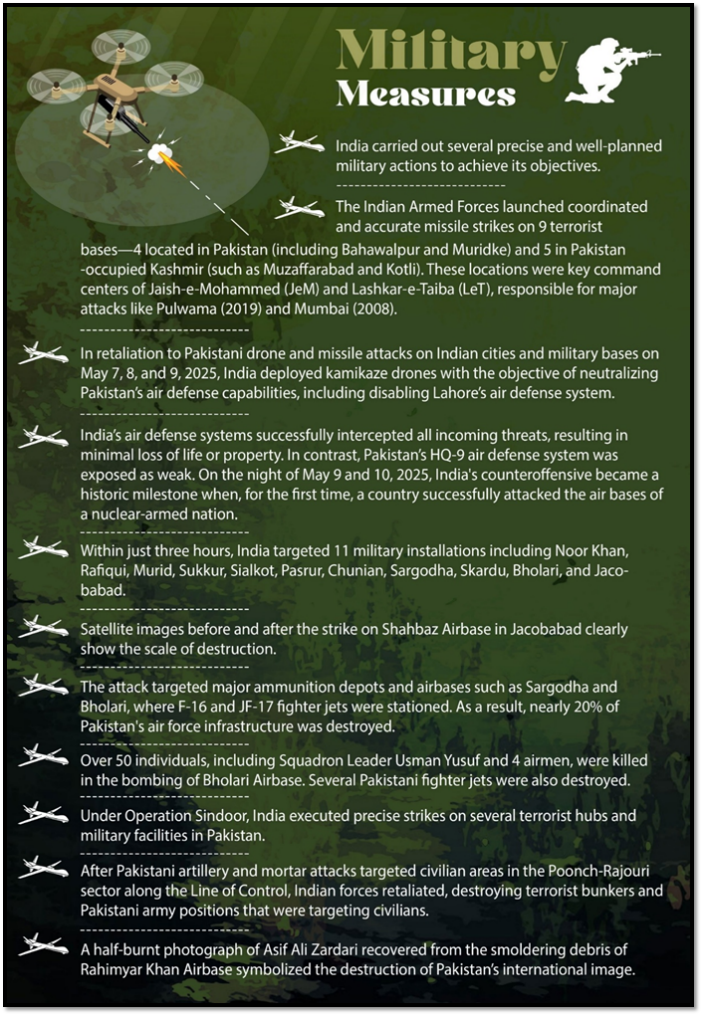

- Neutralisation of Terror Infrastructure:

- Nine major terror camps of Lashkar-e-Taiba, Jaish-e-Mohammed, and Hizbul Mujahideen in Pakistan and PoJK were destroyed.

- Over 100 terrorists were neutralised, including high-profile operatives linked to the IC-814 hijack and Pulwama attacks.

- Deep Cross-Border Precision Strikes:

- Strikes penetrated deep into Pakistani territory, including Bahawalpur and Punjab province, previously considered red zones.

- Signaled India’s intent to strike beyond the LoC if terrorism is state-sponsored.

- Technological Superiority Demonstrated:

- The Indian Air Force used Rafale jets, SCALP missiles, and HAMMER bombs with precision.

- Pakistan’s air defences, including Chinese-origin systems, were bypassed or jammed, exposing vulnerabilities.

- Air Defence Success and Indigenisation Push:

- India’s Akashteer system played a key role in intercepting hostile drones and missiles.

- The operation highlighted the strength of indigenous defence capabilities with potential for exports.

- Targeting Sponsors Alongside Terrorists:

- India deliberately eliminated support infrastructure and backers, breaking the long-standing distinction between terrorists and their enablers.

- Limited Escalation, Maximum Precision:

- Civilian casualties and collateral damage were avoided, showcasing India’s calibrated and ethical use of force.

- Avoided escalation into a wider war, maintaining regional stability.

- Airstrikes on Military Installations:

- On May 9–10, India targeted 11 Pakistani military airbases, destroying nearly 20% of Pakistan’s air assets, including strategic fighter jets at Bholari Air Base.

- Tri-Service Coordination:

- The operation saw seamless coordination between the Army, Navy, and Air Force, reflecting enhanced joint operational readiness and synergy.

- Strategic Messaging and Global Support:

- Operation SINDOOR sent a powerful diplomatic message: India will act decisively without seeking international approval.

- Gained unprecedented global support, with many nations endorsing India’s right to self-defence.

- Narrative Shift on Kashmir:

- India reframed the conflict as a counter-terrorism response, delinking it from the Kashmir political issue.

- Helped reshape international perception towards a security-driven understanding of the region.

Strategic Significance:

- Deterrence Reinforced: The operation demonstrated India’s zero-tolerance policy toward cross-border terrorism, and its readiness to retaliate with force without fear of nuclear escalation.

- Escalation Management: India avoided civilian casualties and military assets, preserving regional stability while asserting its security interests.

- Technological Independence: The deployment of indigenously developed systems like Akash, IACCS, and domestically integrated ISR networks reflects India’s growing self-reliance in defence.

- Integrated Warfare Capability: The operation showcased tri-service coordination, real-time intelligence sharing, and command integration, marking a shift towards network-centric warfare.

- Regional Security Messaging: Operation SINDOOR conveyed a strong warning to both state and nonstate actors that India will respond decisively to cross-border terror threats.

- Diplomatic Leverage: India’s growing global stature allowed it to manage international reactions, shaping the narrative on its own terms.

Conclusion:

Operation SINDOOR was not merely a military strike — it was a comprehensive assertion of India’s strategic autonomy, moral clarity, and operational capability. It represents a new doctrine in India’s national security playbook, where state-sponsored terrorism is countered with calibrated force and diplomatic finesse. The operation will likely serve as a benchmark for future counter-terror policies and reinforce India’s position as a responsible yet resolute regional power.

Chapter 2: Synergy of India’s Armed Forces

In response to the Pahalgam terror attack (April 22, 2025), which killed 26 civilians, India launched Operation SINDOOR on May 7, 2025. It marked a major tri-services military campaign aimed at dismantling terror infrastructure across the LoC and deep inside Pakistan.

Key Highlights:

- Tri-services Coordination: The Indian Army, Air Force, and Navy operated in full synergy, showcasing India’s capability for multi-domain warfare.

- Intelligence-led Strategy: Multi-agency intel confirmed and enabled targeted strikes on nine terror camps, minimizing collateral damage.

- Air Operations: IAF executed precision strikes on key air bases (e.g., Nur Khan, Rahim Yar Khan), maintained airspace integrity through layered air defense using systems like Akash, Pechora, and OSAAK.

- Army’s Role: Efficient in both defensive/offensive roles, the Army neutralized drone attacks with LLADs, MANPADS, and long-range SAMs.

- Navy’s Presence: Asserted maritime superiority using a Carrier Battle Group; enforced a maritime nogo zone near Pakistan’s Makran coast, preventing aerial incursions.

- BSF Action: Foiled infiltration at Samba sector, J&K, neutralizing terrorists and seizing weapons.

Technological Integration: Use of Integrated Command and Control Strategy (ICCS) and net-centric operations enabled real-time coordination and threat interception.

Major Government-Led Coordination Efforts among the Armed Forces

Chief of Defense Staff (CDS) & Department of Military Affairs (DMA): Created on 24 Dec 2019, the CDS is a 4-star General and principal military adviser to the defense minister.

Key Roles of the CDS:

- Leadership & Oversight: Heads the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Territorial Army; leads tri-service organisations including cyber and space commands.

- Jointness & Integration: Promotes jointness in procurement, training, staffing, and restructuring of commands; fosters integration for a unified and modern force.

- Strategic Planning & Advisory: Advises the Nuclear Command Authority; participates in defence planning; drives reforms to optimise resources and enhance combat efficiency.

- Acquisition & Resource Optimisation: Implements multi-year defence acquisition plans, aligns interService priorities, and reduces redundancy and waste.

Integrated Theatre Commands (ITCs): ITCs and Integrated Battle Groups (IBGs) aim to unify tri-service capabilities by geography/function, enhance jointness, and separate operational from Raise-Train-Sustain (RTS) roles.

- Proposed commands include Land, Maritime, and Air Defense domains. CDS Gen Anil Chauhan emphasized jointness for multi-domain, data-centric warfare.

Inter-Services Organizations Act, 2023: Empowers commanders of tri-service formations to exercise disciplinary control across services, enabling unified command, faster decisions, joint culture, and legal backing for ITCs, while retaining individual service identity.

Joint Logistics Nodes (JLNs): Operational since 2021 at Mumbai, Guwahati, Port Blair. Provide integrated logistics (ammunition, rations, fuel, engineering, etc.), saving manpower, resources, and costs.

Joint Training, Seminars & Exercises:

- Tri-Services Future Warfare Course: Initiated by CDS for Majors to Major Generals; 1st held in Sept 2024, 2nd in Apr–May 2025, focused on modern tech-based warfare.

- DSTSC (10 June 2024, MILIT Pune): 166 officers (Army, Navy, IAF, Coast Guard, foreign nations); first triservice joint training.

- Parivartan Chintan (8 Apr 2024): Brainstorming for joint structures.

- Seminar (25 Feb 2025): On Air-Naval synergy in IOR by HQ Southern Air Command & CAPS.

- Exercise Prachanda Prahar (25–27 Mar 2025): Tri-service high-altitude operation in Arunachal.

- Exercise Desert Hunt (24–28 Feb 2025): Joint SF drill with Para SF, MARCOS, Garud at Jodhpur.

Technology & Network-Centric Warfare:

- Defense Communication Network (DCN): Secure, indigenous tri-service network supporting voice/ data/video; a Make in India success.

- Integrated Air Command and Control System (IACCS): Enables real-time joint coordination; proved effective post-Operation SINDOOR.

- ‘Year of Defense Reforms’ – 2025: Declared by MoD to boost jointness, establish ITCs, improve inter-service cooperation, and enable multi-domain integrated operations.

Chapter 3: Rural Prosperity Through Warehousing

Despite the rapid expansion of Kisan Credit Cards (KCCs) in India, the post-harvest credit segment remains severely underutilized.

- In FY 2023–24, India’s total agricultural credit was approximately ₹25 lakh crore, of which short-term credit (mainly for crop cultivation) accounted for ₹14.8 lakh crore.

- However, post-harvest loans were just ₹0.35 lakh crore—a mere 1.4% of total agricultural credit. This low uptake is mainly due to:

- Banks’ reluctance to finance against stored produce (pledged loans),

- Risk of misappropriation or fraud in unregulated warehouses,

- Lack of proper legal recourse and enforcement mechanisms.

Mismatch in Production and Storage

According to NABARD (2024), India’s agricultural warehousing capacity is 239.70 MMT, while food grain production stood at 328.85 MMT, creating a gap of nearly 90 MMT.

- This mismatch limits farmers’ ability to store produce and wait for better prices, forcing distress sales at harvest time.

Economic Benefits of Warehousing

Warehousing offers much more than just storage:

- Scientific storage prevents post-harvest losses from pests, moisture, and handling.

- Electronic Negotiable Warehouse Receipts (e-NWRs) issued by WDRA-registered warehouses can be traded or used to secure bank loans.

- Warehousing supports price realization. Agmarknet data shows that deferring sale of crops like paddy (basmati), turmeric, chilli, and jeera by even a few months after harvest leads to significantly better prices.

- A study by IIM Bangalore found that a 1% increase in warehouse capacity reduces price volatility by 2.0% for wheat and 2.7% for masur, thus stabilising farmer incomes.

Warehouses also help reduce price spread between wholesale and retail, benefitting both producers and consumers. Given that food and beverages constitute 54.18% of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) basket, stabilising food prices has a major impact on inflation control.

India's Agricultural and Rural Profile

- 68.85% of India’s population lives in rural areas (Census 2011).

- 58.4% of the rural workforce is still engaged in agriculture.

- NITI Aayog projects that rural population will remain above 50% till 2045.

- India’s foodgrain production target for 2025–26 is 354.64 MMT.

- Final estimates for 2023–24 (Ministry of Agriculture):

- Foodgrains: 3322.98 LMT

- Oilseeds: 396.69 LMT

- Sugarcane: 4531.58 LMT

- Cotton: 325.22 lakh bales

- Jute & mesta: 96.92 lakh bales

Despite this high productivity, marketing, storage, and price realisation remain weak links in the agri-value chain.

Key Challenges in Agricultural Warehousing

- Storage Shortage: A significant gap (~90 MMT) exists between agri-production and available warehousing capacity.

- Small Warehouse Sizes: Over 68% of India’s 51,307 warehouses have capacities of less than 500 tonnes, making them unsuitable for professional management and scientific storage.

- Skewed Distribution: Most warehouses are concentrated in a few states. The Gangetic belt—a key production region—is underserved, affecting cereals, pulses, and oilseeds.

- Low Farmer Awareness: A MANAGE study revealed poor awareness among farmers regarding:

- Post-harvest pricing trends

- Pledge financing

- e-NWR benefits

- Government schemes

- Regulatory Gaps: As per the Warehousing (Development and Regulation) Act, 2007, only warehouses issuing e-NWRs must register with WDRA. This allows others to remain unregulated, reducing fiduciary trust among farmers and banks.

- Banking Hesitation: Due to past experiences of fraud and poor recovery, many public sector banks are wary of financing warehouse-stored produce.

Government Initiatives to Bridge the Gap

- Agriculture Infrastructure Fund (AIF)

- Outlay: ₹1 lakh crore

- Purpose: Build post-harvest infrastructure including cold chains, silos, and warehouses

- Special focus on farm-gate infrastructure

- World’s Largest Grain Storage Plan

- To be implemented via PACS (Primary Agricultural Credit Societies)

- Also backed by ₹1 lakh crore investment to build storage at the grassroots

- Credit Guarantee Scheme for e-NWR Pledge Finance (CGS-NPF)

- Outlay: ₹1000 crore

- Provides guarantee cover to banks lending against e-NWRs

- Focuses on small and marginal farmers, with higher coverage and lower fees

- Interest Subvention Scheme

- Offers 1.5% interest subvention on loans against e-NWRs for small/marginal farmers with KCCs

- Aims to reduce cost of borrowing

- e-Kisan Upaj Nidhi Portal

- Digital platform for quick loan approvals

- Integrated with banks, credit bureaus, WDRA, and e-NAM

- Enables farmers to select banks of their choice and receive in-principle loan approval rapidly

- Infrastructure Development Programs

- Private Entrepreneurs Guarantee Scheme (PEG)

- Construction of Silos under PPP

- Warehousing Infrastructure Fund

Conclusion and Way Forward

A robust, well-regulated warehousing ecosystem can transform India’s agricultural economy. It can:

- Help farmers avoid distress sales

- Provide post-harvest liquidity

- Stabilise prices and reduce inflation

- Promote rural income growth and food security

Key priorities moving forward:

- Expand scientific and scalable storage infrastructure in surplus zones.

- Mandate WDRA registration for all warehouses to ensure uniform regulation.

- Increase awareness among farmers about warehousing benefits, price trends, and credit instruments.

- Encourage bank participation in post-harvest finance by enhancing risk mitigation frameworks.

A multi-pronged policy approach can unlock the full potential of agri-warehousing and drive inclusive rural prosperity.

Chapter 4: Safe Food for a Healthy India

Food safety is an essential aspect of public health, economic development, and national food security. In India, where agriculture employs nearly half the population and food consumption is a daily concern for 1.4 billion people, ensuring food safety from farm to fork is both a challenge and necessity.

The Scope and Importance of Food Safety

- Definition: Food safety involves handling, preparing, storing, and distributing food in ways that prevent contamination and foodborne illnesses.

- Hazards addressed include:

- Biological: Bacteria (e.g., E. coli, Salmonella), viruses (e.g., Hepatitis A), fungi (e.g., aflatoxins), parasites

- Chemical: Pesticide residues, heavy metals (e.g., lead, arsenic), additives, toxins from poor storage.

- Physical: Glass, plastic, or metal fragments during processing.

Why it matters:

- According to WHO, unsafe food causes 600 million illnesses and 4.2 lakh deaths globally each year.

- In India, foodborne diseases like diarrhoea, cholera, and pesticide poisoning are rampant, especially affecting children.

- Food safety impacts:

- Public health

- Farmer livelihoods

- Trade competitiveness

- Consumer trust

- Environmental sustainability

Key Challenges in India’s Food Safety Ecosystem

A. Excessive Pesticide Use

- India ranks 4th globally in pesticide consumption.

- Pesticide residues above permissible limits are commonly found in fruits, vegetables, and grains.

- Banned pesticides like monocrotophos are still used in some regions.

- Consequences:

- Long-term health effects including cancer and neurological disorders.

- Soil and water contamination.

- Export rejections due to residue levels exceeding Codex/European Union norms.

Solution: Promote Integrated Pest Management (IPM), organic farming, stricter regulation enforcement, and farmer training.

B. Post-Harvest Handling and Infrastructure Deficit

- India loses nearly 30% of food produce annually due to poor storage and transport.

- Grains stored in open areas often develop aflatoxins, a carcinogenic fungus.

- Lack of cold chains, hygienic processing, and scientific storage affect food quality and safety

- Small and marginal farmers lack access to post-harvest technologies.

Solution: Invest in:

- Modern warehouses and cold chains (e.g., under Agriculture Infrastructure Fund).

- Training for farmers on safe storage and handling.

- Digitisation and traceability tools (e.g., blockchain).

C. Widespread Food Adulteration

- According to FSSAI (2018), 68% of milk samples in India were found adulterated.

- Common adulterants include:

- Urea, starch, and detergents in milk.

- Metanil yellow in turmeric.

- Argemone oil in mustard oil.

- Artificial colours and low-quality oils in spices and sweets.

- Such adulteration can cause organ damage, cancer, and food poisoning.

Solution:

- Strengthen food testing laboratories (especially at the district level).

- Enforce stricter penalties under FSS Act, 2006.

- Promote citizen reporting, use of QR codes and mobile-based testing tools.

D. Weak Implementation of Food Safety Laws

- The Food Safety and Standards Act (FSSA), 2006, is poorly implemented in rural and informal markets.

- FSSAI lacks manpower and infrastructure to monitor millions of food vendors, especially in Tier-II and Tier-III cities.

Solution:

- Decentralise food safety enforcement through panchayats and municipal bodies.

- Increase recruitment and training of food safety officers.

- Ensure registration/licensing of all food business operators (FBOs).

E. Lack of Awareness and Hygiene Practices:

- Many small farmers and street food vendors are unaware of hygiene protocols, such as washing produce, sanitising tools, or wearing gloves.

- Street food is often prepared in unsanitary conditions, increasing disease transmission risks.

- Consumers are also not educated enough to distinguish safe from unsafe food.

Solution:

- Launch mass awareness campaigns like Eat Right India.

- Introduce food safety curriculum in schools and agricultural training institutes.

- Encourage self-regulation models, hygiene ratings, and consumer feedback systems.

Economic and Global Trade Impacts

- Food safety is critical for India’s agro-export potential.

- High-value exports like spices, seafood, and basmati rice face frequent rejections due to contamination.

- These result in billions in losses and damage India’s global brand reputation.

- Safe food opens up access to premium international markets, helping farmers earn better prices and incomes.

Government Interventions

- FSSAI Initiatives:

- Eat Right India campaign

- Safe and Nutritious Food (SNF) awareness drives

- Clean Street Food Hubs

- Policy Reforms:

- Strengthening Food Recall Mechanisms

- Launch of Food Safety Compliance System (FoSCoS) portal

- Schemes Promoting Safety & Hygiene:

- PM Formalisation of Micro Food Processing Enterprises (PM-FME)

- Agri-Infra Fund for better storage

- Kisan Rail and Kisan Udan to speed up farm-to-market access

Key Challenges in Ensuring Food Safety

- Fragmented Supply Chains: India’s agricultural supply chain involves multiple intermediaries, leading to higher risks of contamination and lack of traceability. Traditional mandis are poorly equipped to track the origin of spoilage or adulteration.

- Economic Constraints of Farmers: Small and marginal farmers often lack access to safe storage, quality inputs, and affordable technologies. Financial constraints and dependence on middlemen hinder adoption of food safety measures.

- Infrastructure Gaps: India has fewer than 200 accredited food testing labs against a requirement of over 500. Less than 10% of perishable goods have access to cold storage, resulting in high post-harvest losses and food contamination.

- Adulteration and Pesticide Residues: Rampant use of chemical pesticides and banned substances like monocrotophos has led to harmful residues in produce. Food adulteration—especially in milk, oils, and spices—poses a major public health threat.

- Export Rejections: Indian agro-exports, particularly basmati rice and spices, often face rejections in global markets due to pesticide residues, causing estimated losses of $15–20 billion annually.

Way Forward

- Farmer Education and Good Agricultural Practices (GAP): Training programs through Krishi Vigyan Kendras (KVKs) and NGOs can promote safe pesticide use, hygienic harvesting, and awareness on residue limits.

- Promotion of Organic and Natural Farming: Expanding schemes like Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana (PKVY) and Bhartiya Prakritik Krishi Padhati (BPKP), along with subsidies for organic inputs and certification, can encourage a shift to sustainable agriculture.

- Strengthening Infrastructure: Investments are needed in cold chain logistics, food testing laboratories, and modernised storage and processing facilities. Upgrading APMCs with integrated food safety checks is also vital.

- Technology for Transparency: Use of blockchain for farm-to-fork traceability and AI-based advisory tools can reduce risks and improve decision-making at the farm level.

- Policy Reform and Regulatory Enforcement: Expanding FSSAI’s outreach in rural areas, imposing strict penalties for violations, and conducting regular inspections can ensure compliance with food safety standards.

- Consumer Awareness: Campaigns like ‘Eat Right India’ must be scaled up, along with mandatory food safety labelling, to promote informed consumer choices and create demand for safer food.

Conclusion:

Food safety is integral to India’s sustainable development goals. A comprehensive strategy involving policy reform, technological innovation, farmer empowerment, and consumer participation is essential to build a resilient and trustworthy food system. By ensuring safety from farm to fork, India can protect public health, enhance farmer incomes, and strengthen its position in global agricultural trade—paving the way for a healthier, more prosperous future.

Chapter 5: Opportunities and Challenges in India’s Food Export Sector

India’s food export sector plays a crucial role in its foreign exchange earnings and rural development. As one of the world’s largest producers of agricultural products, India holds untapped potential in expanding its global market share.

- While recent trends point to increasing exports of processed foods and diversification into high-value products, multiple structural and policy-related challenges continue to constrain the full realization of this sector’s potential.

Significance of the Food Export Sector

Agriculture is the primary source of livelihood for a significant proportion of India’s population. India is among the top producers of rice, wheat, pulses, fruits, vegetables, and dairy. Food exports contribute in several key areas:

- Foreign Exchange Earnings: Major source of export revenue, reducing the trade deficit.

- Employment Generation: Especially in rural areas, through agriculture, food processing, and allied sectors.

- Rural Development: Enhanced income, infrastructure development, and access to education and health services.

- Poverty Alleviation: Direct impact on farmer incomes and local economies.

Despite these advantages, India’s share in global agricultural exports remains modest at around 2.4%, indicating a vast untapped potential.

Current Export Scenario and Decline

India was aiming for $60 billion in agri-exports by 2022 under the Agriculture Export Policy (AEP) 2018, but actual exports in 2023-24 stood at $48.8 billion, down from $53.2 billion in the previous fiscal year.

- This 8% decline underscores the need for strategic policy realignment and infrastructural improvement.

Government Initiatives and Institutional Framework

Several key policy and institutional frameworks support food exports:

- Agriculture Export Policy (AEP) 2018: Aims to diversify the export basket, promote high-value and organic produce, and integrate Indian farmers into global value chains.

- APEDA: Facilitates agricultural exports with quality certifications, infrastructure support, and market intelligence.

- Financial Assistance Scheme (FAS) and Trade Infrastructure for Export Scheme (TIES): Promote investment in export-related infrastructure and market development.

- Market Access Initiative (MAI): Supports exporters in discovering and penetrating new markets.

Key Challenges Hindering Growth

India’s agricultural export sector faces multiple challenges:

- Export Uncertainty: Frequent bans (e.g., on rice, sugar) create global unreliability.

- Concentration on Few Commodities: Overdependence on rice and sugar makes exports vulnerable to price and demand shocks.

- Infrastructure Deficit: Lack of cold chains, storage, and transport reduces efficiency.

- Quality Standards: Many exports fail to meet international hygiene and phytosanitary norms.

- Global Competition: Nations like Vietnam (rice), Brazil (sugar), and Thailand (processed foods) offer stiff competition.

Opportunities and Strategic Directions

Despite these hurdles, India’s food export potential remains robust:

- Diversification: Emphasis on high-value products like spices, ready-to-eat meals, millets, organic produce, and fruit concentrates.

- Sustainability: Pulses and oilseeds, which require less water, align with global eco-trends.

- New Markets: Rising demand in Middle East, Africa, East Asia, and EU for Indian staples and specialty products.

- Technological Integration:

- Blockchain for traceability and compliance

- Precision Farming to enhance productivity

- Digital platforms to streamline logistics and document management

- Brand Building: Positioning Indian products like Basmati rice, spices, and organic items as premium global brands.

Advantages of Processed Food Exports

Processed food exports offer significant economic and logistical benefits:

- Longer Shelf Life: Reduces post-harvest loss and increases export feasibility.

- Value Addition: Enhances profitability and marketability.

- Branding and Market Expansion: Allows product customization for different regions and culinary preferences.

- MSME Participation: Boosts employment and rural entrepreneurship.

In 2023–24, processed food exports reached USD 7.7 billion, with strong growth in categories like mango pulp, cereal preparations, and processed vegetables.

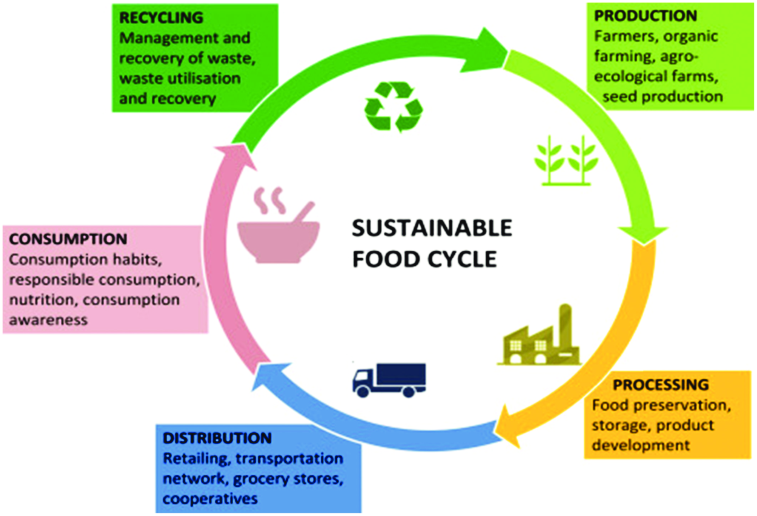

The Circular Economy: A Sustainable Approach to Food Exports

India must align its food processing and export sectors with Circular Economy (CE) principles to ensure longterm sustainability and global competitiveness. CE practices can:

- Reduce Wastage: Through sustainable farming and improved logistics.

- Utilise By-products: Creating new revenue streams from agricultural residue.

- Enhance Packaging: Use biodegradable and eco-friendly materials.

- Optimize Supply Chains: Reduce energy use and enhance transport efficiency.

- Meet Global Norms: Tapping into markets with strict environmental regulations.

Government support through incentives, capacity building, and regulatory frameworks will be essential for CE integration.

Way Forward and Conclusion

India’s food export sector, if nurtured through strategic reforms, infrastructure development, and sustainability practices, can emerge as a global leader. The government must focus on:

- Stable Export Policies

- Investment in R&D and Infrastructure

- Skill and Quality Development

- Encouragement for Food Processing and Innovation

Incorporating Circular Economy principles will not only make Indian products more sustainable but also more attractive to environmentally conscious global consumers. With the right interventions, India’s food export can contribute significantly to inclusive economic growth, rural development, and global food security.

UPSC Mains Practice Question

Q1. How can India leverage food processing and circular economy principles to transform its food export sector? Evaluate the impact of these strategies on sustainability, rural development, and foreign trade.

Q2. “Ensuring food safety is not just a public health imperative but also an economic and strategic necessity for India.” In this context, discuss the major challenges in India’s food safety ecosystem and suggest a multi-pronged strategy to address them

QUICK LINKS