Down To Earth (16-31 January 2026)

The following topics are covered in the Down To Earth (16-31 January, 2026)

From Clean Cities to Contaminated Water: Hidden Crisis Beneath Indore’s Tragedy

Context

- Indore, India’s cleanest-ranked city, recently faced deaths caused by contaminated drinking water.

Water Supply and Sewage

- Every litre of water supplied to households eventually returns as wastewater by 80%. But, most urban governance focuses on providing water, not managing what flows back.

- India’s flagship urban mission, the Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT), acknowledges the importance of water and sewage management. But, the spending pattern reveals misplaced priorities:

- 62% of funds directed to water supply;

- 34% to sewerage projects;

- Only 3% to rejuvenating waterbodies;

- The majority has gone into expanding supply, not managing waste out of ₹1.93 lakh crore spent on 3,500 projects.

- This imbalance needs to change, not by spending more, but by redesigning smarter, affordable systems.

A Sewage-First Approach: Affordable, Inclusive, and Circular

- Use Onsite Systems as the Foundation: Onsite systems need not be a liability, they can be a sustainable solution if properly managed.

- Toilets need to be regularly desludged, and excreta needs to be transported to treatment sites where water and solid waste are recycled as usable resources (for irrigation or manure).

- Redesign AMRUT for Sewage Priority: AMRUT guidelines should shift from water-centric to sewage-first frameworks, emphasizing:

- Full interception of household excreta;

- Use of existing septic tanks and tanker-based transport to treatment sites

- Performance-based financing tied to the volume of wastewater and sludge reused

- Integrate Water Projects with Local Sources: Reconnecting water supply to local waterbodies is essential.

- It reduces dependence on distant sources, cuts energy use, and promotes groundwater recharge.

- However, this is only possible if local lakes and reservoirs remain free from sewage pollution, making wastewater treatment a prerequisite for water security.

Madhav Gadgil: Ecologist Who Made Kerala Rethink Development

Context

- Recently, Madhav Gadgil, celebrated ecologist, academic, and founder of the Centre for Ecological Sciences at the Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru, passed away at the age of 83.

Madhav Gadgil (1943–2026): Architect of Ecological Thinking in India

- Early Life and Academic Journey:

- Born in Pune, Maharashtra, Graduated from the University of Pune and PhD in Zoology from Harvard University.

- Later founded and led the Centre for Ecological Sciences (CES) at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc), Bengaluru.

Key Contributions and Ideas

- Chairman of Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel (WGEEP), set up by India’s Ministry of Environment and Forests in 2010.

- The Gadgil Report (2011) provided a landmark scientific framework for conserving the ecologically sensitive Western Ghats, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

- Key Recommendations:

- Classifying the Ghats into Ecologically Sensitive Zones (ESZs) based on environmental fragility.

- Promoting decentralized governance through local bodies (gram sabhas).

- Restricting mining, quarrying, and large-scale construction.

- Advocating sustainable livelihoods rather than blanket bans.

- People’s Biodiversity Registers (PBRs): Gadgil pioneered the concept of People’s Biodiversity Registers, a system for documenting local ecological knowledge, species diversity, and community practices.

- These registers empowered local communities to take part in managing their biological resources, laying the groundwork for India’s Biological Diversity Act (2002) and subsequent Biodiversity Management Committees (BMCs) across the country.

- Linking Science, Democracy, and Ecology: Gadgil consistently argued that ecological science must be democratic, accessible to ordinary people and accountable to their realities.

- He believed that conservation should not come at the cost of livelihoods, but should integrate community wisdom with scientific understanding.

- His approach contrasted with top-down models of conservation, often led by bureaucracies disconnected from ground realities.

- Work on Ecological History and Human-Nature Relationships: Gadgil’s research extended beyond environmental policy into human ecology, studying how societies interact with ecosystems over time.

- Silent Valley Movement and Early Environmental Advocacy: Gadgil questioned the proposed hydropower dam in Kerala’s rainforest during the Silent Valley controversy of the 1970s–1980s.

- He put scientific legitimacy to grassroots environmental activism, influencing public perception that development projects must pass ecological scrutiny.

- Advisory and Global Roles: Served on the Scientific Advisory Council to the Prime Minister of India.

- Member of several international panels on biodiversity, conservation, and sustainable development, including for the UNESCO Man and Biosphere Programme.

- Recipient of prestigious honors such as the Padma Bhushan (2006) for his contributions to environmental science and policy.

US Seizure of Venezuela: Oil, Power, and Global Repercussions

Context

- Recently, US forces entered Venezuela and abducted President Nicolás Maduro and his wife, and later Trump promised a US-led overhaul of Venezuela’s oil sector, declaring that American energy firms would ‘go in, spend billions of dollars, fix the badly broken infrastructure’.

Venezuela : World’s Largest Oil Reserves

- Venezuela holds 303 billion barrels of crude oil, around 18% of global proven reserves, yet it produces barely 1 million barrels per day (bpd), a fraction of its 1990s peak of 3.5 million bpd.

- The heavy crude from Venezuela makes up about two-thirds of national production and roughly 4.5% of global heavy oil supply.

- Such crude is particularly suited to U.S., Chinese, and Indian refineries designed for dense, sulfur-rich oil.

- Years of economic mismanagement, sanctions, and infrastructure decay have reduced output to historic lows.

Impact on Oil Markets

- Brent crude briefly rose above $60 per barrel, while West Texas Intermediate (WTI) hovered around $55, before easing when Trump imposed a blockade on Venezuelan shipping in mid-December 2025.

- Following Maduro’s capture, prices firmed slightly, Brent between $60–61 and WTI between $56–58.

Winners and Losers

- US Diversion Strategy: More Venezuelan crude redirected to US refineries, reducing availability in Asia.

- Instability Scenario: Political and security chaos that disrupts exports entirely.

- Both scenarios threaten Asian importers, especially China and India, which rely on heavy crude.

- In the long term, even if Venezuela stabilizes under US control, most new production will likely flow to American refineries, which hold the world’s largest heavy oil refining capacity.

India’s Limited Exposure

- Past sanctions had already curtailed imports of Venezuelan crude.

- However, Indian public-sector firms such as ONGC Videsh, IOC, and Oil India hold stakes in Venezuelan projects worth hundreds of millions in unrepatriated dividends, about $536 million since 2014.

Reviving the Petrodollar Debate

- Beyond oil flows, the intervention revives discussion around the petrodollar system, the global practice of trading oil in US dollars, which anchors America’s financial dominance.

Petrodollar System

- Origins and Mechanics of the Petrodollar: Nearly all crude oil has been priced and traded in US dollars, regardless of its origin or destination since the 1970s.

- It compels oil-importing nations to maintain large dollar reserves to secure energy imports, reinforcing global demand for the greenback.

- Meanwhile, oil-exporting countries accumulate vast dollar revenues, which are frequently recycled into US Treasury Bonds and financial markets.

- It finances America’s budget deficits and cements the dollar’s role as the world’s dominant reserve currency.

Attempts to Challenge the System

- Venezuela earlier sought to sell oil in Euros, Yuan, and even digital assets to sidestep US sanctions.

- However, these initiatives were constrained by limited export volumes and restricted access to international financial networks.

- Venezuela managed to sustain oil production near 900,000 barrels per day, with China emerging as its principal buyer despite sanctions.

- China supported Venezuela through currency swap arrangements and investments in Venezuelan oil fields, signaling a potential long-term shift toward de-dollarized trade.

Strategic Implications for the United States

- The dollar-based oil trade provides the U.S. with crucial economic advantages:

- It lowers borrowing costs by ensuring continuous demand for US debt.

- It supports large-scale government spending without triggering capital flight.

- It enhances the power of U.S. financial sanctions, enabling asset freezes and trade restrictions that can cripple targeted economies.

India’s Nuclear Power Reforms Under the SHANTI Act, 2025

Context

- A new comprehensive law opens up the nuclear sector to private players, while diluting disaster liability and safety provisions

About SHANTI Act, 2025

- The Sustainable Harnessing and Advancement of Nuclear Energy for Transforming India (SHANTI) Act, 2025 repeals the Atomic Energy Act, 1962 and the Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage Act, 2010, ending the government’s monopoly over nuclear power generation.

- It opens the sector to private and foreign participation in areas including uranium mining, reactor construction, operation, and manufacturing, subject to licensing and regulatory oversight.

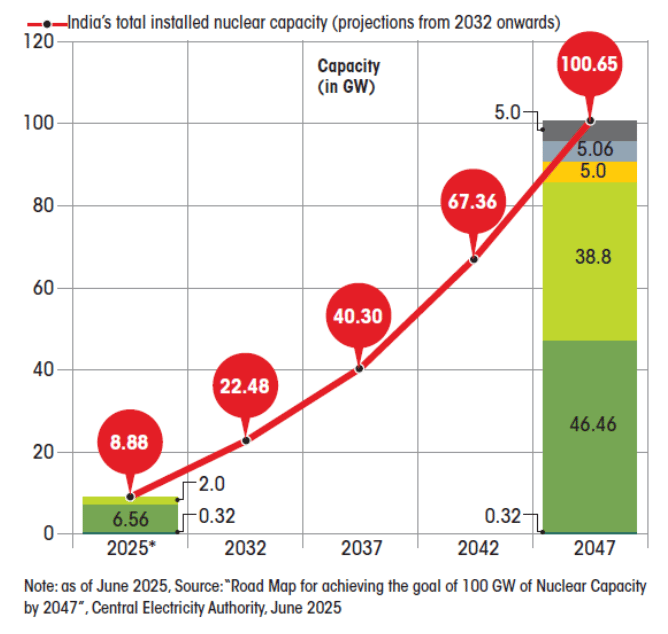

- India’s Nuclear Energy Mission targets 100 GW of installed nuclear capacity by 2047.

- Boiling Water Reactor: Generates electricity by boiling water in reactor vessel;

- Fast Breeder Reactor: Uses a liquid sodium coolant and converts fertile uranium-238 or thorium-232 into usable fuel, crucial for India that has large thorium reserves;

- Pressurised Heavy Water Reactor (PHWR): Uses deuterium oxide as both coolant and moderator, allowing use of natural, unenriched uranium as fuel;

- Light Water Reactor: Uses ordinary water as both coolant and moderator, using low-enriched uranium as fuel. Pressurised Water Reactor (PWR) is a common variant of this technology, using pressure to keep the water from boiling;

- Bharat Small Reactor: Compact 220 MW PHWRs being developed with private sector participation;

- Bharat Small Modular Reactor: Compact reactors (around 200 MWe) being developed using PWR technology;

Private and Foreign Entry into Nuclear Power

- Foreign direct investment (FDI) up to 49% is permitted, enabling private partnerships and joint ventures under the Act.

- The move marks a major structural shift in India’s nuclear governance while NTPC and other public entities like NPCIL will retain control over sensitive parts of the fuel cycle.

- As of mid-2025, India’s installed nuclear capacity stands at 8.8 GW, contributing around 3% of total electricity generation, a 71% rise since 2014.

- Another 10 reactors (8 GW) are under construction, with 10 more in pre-project stages, potentially taking capacity to 22.5 GW by 2031–32.

Pursuit of Small Modular Reactors

- India is emphasizing indigenous technology, notably the 200-MW Bharat Small Modular Reactor (BSMR) under development at the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (BARC).

- Nuclear power has historically hovered between 2–4% of India’s electricity mix.

Concerns Over Safety and Control

- Weaken Regulatory Safeguards: Granting operational control of fissile material to private entities increases the risk of catastrophic accidents.

- The Act introduces composite licenses, allowing a single entity to operate across multiple stages of the fuel cycle, potentially concentrating systemic risk.

- Capped Liability and the Moral Hazard Debate: Section 13 of the Act caps nuclear liability at 300 million Special Drawing Rights (SDRs).

- The government assumes liability beyond this amount.

- The Act removes the operator’s right of recourse against suppliers, effectively shielding foreign equipment providers.

- Regulatory Oversight and Exemptions: The SHANTI Act allows the Union government to appoint board members of Atomic Energy Regulatory Board (AERB), and Section 44 empowers it to exempt any facility or technology from licensing or liability if deemed of ‘insignificant’ risk, a term left undefined.

- Further, Section 39 enables the government to restrict publication of nuclear information, overriding the Right to Information Act.

- Economic Viability and Investment Challenges: Nuclear plants are capital-intensive with long gestation periods.

- The success depends on predictable tariffs, power purchase agreements, and dispute resolution frameworks.

- Operational Reality and Resource Allocation: According to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and the World Nuclear Industry Status Report 2025, seven Indian reactors are in ‘suspended operation’ or ‘long-term outage’ due to ageing and technical issues.

- These reactors are still counted in capacity statistics, masking operational shortfalls.

Dismantling of MGNREGA & Critical Look at the VB-G RAM G Act, 2025

Context

- The Union government repealed the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, 2005 (MGNREGA) and replaced it with the Viksit Bharat–Guarantee for Rozgar and Ajeevika Mission (Gramin) Act, 2025, or VB-G RAM G Act.

About the MGNREGA (2005)

- It was the world’s largest social security programme, guaranteed 100 days of wage employment to every registered rural household.

- Its rights-based, demand-driven design made it revolutionary, the State was legally obliged to provide work or pay an unemployment allowance.

- Over a decade, the programme:

- Increased rural employment from 21 million to 55 million person-days.

- Helped 69% of households avoid hunger and reduced migration by 57%.

- Supported coping during illness and prevented hazardous labour.

- Created durable rural assets like roads, water bodies, and afforestation projects.

VB-G RAM G Act, 2025

- From Rights to Allocations: MGNREGA’s legal guarantee of work has been replaced by a centrally sponsored scheme where employment depends on annual allocations decided by the Centre.

- It effectively converts a demand-driven entitlement into a supply-constrained scheme.

- Curtailing State Autonomy: Under Sections 4(6) and 22(5), states can only expand guarantees within procedures defined by the Centre.

- It undermines fiscal federalism and limits states’ ability to respond to local needs.

- Reduced Fiscal Support: Funding has shifted from a 90:10 Centre-State ratio to 60:40, placing heavier burdens on fiscally weaker states.

- Estimates suggest that states collectively would have borne an additional ₹31,000 crore under this formula in FY 2025.

- ‘Switch-Off’ Clause: The Act allows work to be suspended for 60 days during peak agricultural seasons to ensure labour availability for farmers.

- It weakens workers’ bargaining power and may push them back into exploitative labour arrangements.

Significances & Key Justifications

- Raising the guaranteed days from 100 to 125 per household.

- Rationalising permissible works into four themes ie water security, infrastructure, livelihoods, and climate resilience.

- Introducing digital monitoring and concurrent evaluations to curb leakages.

- Ensuring tighter timelines for wage payments and unemployment allowances.

- However, the average employment under MGNREGA has historically been 46–50 days, far below the statutory limit. Thus, merely extending the ceiling does little to enhance actual employment levels.

Related Concerns

- Erosion of Universal Coverage: The new law allows the Centre to notify which rural areas are covered, opening space for arbitrary exclusions.

- Centralised Power: The Centre gains unprecedented control over budget allocations and implementation norms.

- Weakened Federalism: The higher state cost share risks punishing opposition-ruled or financially weak states.

- Supply-Limited Design: Normative allocations replace the open-ended, demand-driven guarantee that made MGNREGA unique.

Did MGNREGA Need Reform?

- Uneven state performance and low capacity in poorer states.

- Delays in wage payments.

- Quality concerns over created assets.

- Leakages and corruption through fake job cards.

- While the new Act attempts to address some of these, particularly through digital tools and normative allocations, most reforms merely formalise existing guidelines rather than innovate.

- Without administrative strengthening, these changes may not improve outcomes.

India’s Tryst With Rural Wage Employment Guarantee

- Rural Manpower Programme 1960: First wage employment programme that aims to provide 100 days of employment to 2.5 million people

- Crash Scheme for Rural Employment, 1971: Three-year programme to provide employment to 1,000 persons per annum in each district, via development projects such as road construction, infrastructure for irrigation, soil conservation, afforestation, land reclamation and other works

- Pilot Intensive Rural Employment Project, 1972: Three-year action-research project offering work to 1,000 people a district for 10 months annually

- Maharashtra Employment Guarantee Act, 1977: State programme guaranteeing employment to all adults who volunteer to do unskilled manual work in rural areas

- Food for Work Programme, 1977: Launched with the intention to reduce rural unemployment and improve nutritional status, with wages partially or fully in foodgrains for people employed in construction and development projects

- Integrated Rural Development Programme, 1978-79: Launched to cater to needs of farmers, workers and families living below the poverty line (BPL), by giving them access to income-generating assets, access to credit and other inputs

- National Rural Employment Programme, 1980: Revised and revamped version of FWP, aiming to generate additional gainful employment for unemployed and underemployed persons in rural areas for 300-400 million human days per year

- Rural Landless Employment Guarantee Programme, 1983: Aims to provide 100 days’ employment to at least one member of each landless rural household

- Jawahar Rozgar Yojana, 1989-90: Merging the provisions of NREP and RLEGP, the programme targets BPL populations, prioritising Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and freed bonded labour. Only unskilled labour work provided, instead of mechanised work, to increase employment

- Employment Assurance Scheme, 1993: Merged with the second stream of JRY, the programme is introduced in 1,775 backward blocks for 100 days of unskilled work during lean agriculture season, for minimum wage

- Swarnajayanti Gram Swarozgar Yojana, 1999: A merger of six programmes, including IRDP, that covers all aspects of self-employment such as organisation of self-help groups, training, credit, technology, infrastructure and marketing

- Jawahar Gram Samridhi Yojana, 1999: Revised JRY, focusing on planned development of village infrastructure assets

- Sampoorna Grameen Rozgar Yojana, 2001: Merger of JGSY and EAS, the programme aims to provide additional and supplementary wage employment, food security and improve nutritional levels in all rural areas

- National Food for Work Programme, 2004: Launched to provide supplementary wage employment in the 150 most backward districts of the country where rural unemployment is high

- MGNREGA (2005): Launched with the provision of mandatory guaranteed wage employment for a minimum of 100 days each year for unskilled labour. The first to recognise work as a right of people

- VB-G RAM G (2025): Replaces MGNREGA, with provisions including 125 days of employment, weekly wage payment, cost sharing between Centre and states

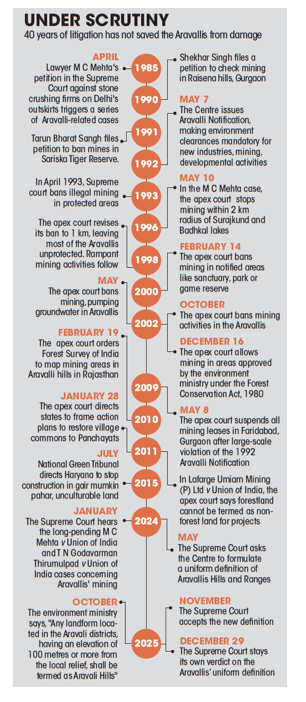

Aravalli Mountain & Supreme Court of India

Context

- Recently, the Supreme Court of India stayed its own judgment that had accepted a ‘uniform definition’ for the Aravalli hills and ranges.

- The earlier ruling had classified Aravalli ‘hills’ as landforms with a minimum elevation of 100 metres above local relief and defined a ‘range’ where two or more such hills lay within 500 metres of each other.

Aravallis Range

- It represents a complex geological history stretching over billions of years. Formed in phases, it includes:

- Bhilwara gneiss (≈3 billion years old)

- Quartzites from mountain-building between 2–1.8 billion years ago

- Post-Delhi magmatic rocks (850–750 million years ago)

- Recent studies reveal that the Aravallis do not end near Delhi but continue underground to Haridwar, forming a buried spine dividing the Ganga and Indus river basins.

- Though the Aravallis appear stable, their Delhi Fold Belt is seismically restless, a zone where ancient faults still react to distant tectonic stresses.

Why the 100-Metre Rule Fails the Aravallis?

- The Aravallis’ ecological functions like sand-barrier formation, aquifer recharge, grassland habitats, and wildlife corridors depend on the continuity of the entire range, not just prominent peaks.

- Analysis using NASA’s Shuttle Radar Topography Mission data found that, under the Supreme Court’s definition, only 9% of the 12,081 mapped hills meet the 100-metre requirement.

- Consequently, over 90% of the Aravalli terrain would be exposed to mining and urbanization.

- Public protests and petitions followed, prompting the Supreme Court to stay its own order and appoint a high-powered committee to re-examine the scientific validity and ecological implications of the 100-metre elevation rule.

Genesis of a Flawed Definition

- In May 2024, the Court directed the Centre to create a uniform definition of the Aravalli hills to avoid conflicting judgments across states.

- The resulting committee, led by MoEFCC, adopted Rajasthan’s 2002 landform classification, which relied on Richard Murphy’s 1968 model defining hills as landforms rising over 100 metres above local relief.

- However, as the committee’s own report noted, the Aravalli terrain shows wide internal variation and cannot be uniformly defined by elevation or slope alone, and it retained the 100-metre threshold, contradicting its findings.

Scientific and Conceptual Critiques

- Applying Murphy’s academic classification to determine land use is scientifically unsound.

- The 100-metre threshold has no universal or ecological basis, as hills vary regionally by relief and environmental context.

- Haryana’s fragile forest cover (just 3.6%) would shrink further if low-elevation areas lost legal protection.

- According to the Geological Survey of India (GSI), the data used to justify the definition was never ground-verified, relying on unverified elevation datasets.

Flawed Process, Legal Ambiguity

- The committee and the Court’s earlier acceptance of its report, arguing that adopting Rajasthan’s mining criteria does not equate to defining the Aravallis.

- There are several procedural inconsistencies like missing signatures from GSI and FSI officials, and the conflation of ‘operational’ and ‘uniform’ definitions.

- The Court itself admitted that public dissent stemmed from ‘ambiguity and lack of clarity’, leading it to pause implementation until further review.

Mining Interests and Policy Loopholes

- The MoEFCC committee identified critical minerals such as lithium, nickel, graphite, and rare earth elements in the Aravalli-Delhi belt, recommending limited mining for ‘strategic and atomic minerals’.

- It could become a loophole for renewed mining, as the line between ‘strategic’ and ‘commercial’ extraction often blurs.

- It is a case of ‘administrative opportunism’, arguing that the ecological impact of lithium drilling is no different from granite quarrying.

- Historical evidence backs his concern: a 2018 Central Empowered Committee (CEC) report found that 25% of the Aravallis in Rajasthan had already been lost to illegal mining since 1967–68.

Environmental Fallout

- The loss of 5,772.7 sq km of forest cover already marks a 32% reduction in the Aravalli’s green cover.

- Further mining could accelerate desertification in Haryana and Rajasthan.

- The Delhi-NCR region faces the threat of deteriorating air quality, depleted groundwater, and loss of climate resilience.

- The forest policy target i.e. 33% forest cover in plains and 66% in hills becomes unattainable under the current height-based classification.

Need for Coherent Judicial and Ecological Policy

- The Court’s order appointing a High-Level Committee to define the Aravallis continues on the flawed premise of facilitating mining rather than ensuring conservation.

- Before drafting any mining plan, the Supreme Court needs to ensure:

- Full compliance with the Ashok Sharma and Godavarman orders.

- Comprehensive GIS-based mapping of all forest categories.

- Protection of PLPA lands, and wildlife corridors.

Groundwater and the Hidden Labour Crisis

Context

- Field and academic evidence shows sharp falls in casual agricultural employment at places where groundwater access declines.

Scale of the Decline

- According to the Central Ground Water Board (CGWB) report Dynamic Ground Water Resources of India 2024, India’s annual groundwater recharge stands at 448.5 billion cubic metres (bcm), with an extractable resource of 407.8 bcm.

- About 247.2 bcm is extracted each year of this..

- In the CGWB’s 2023 block-level assessment, 736 of 6,553 units (11%) were classified as over-exploited, drawing more water than they replenish.

- Hundreds more are critical or semi-critical. These regions are now the epicentres of both hydrological and employment stress.

Linkage of Falling Water Table & Employment

- Casual agricultural labour remains a major source of rural income—roughly one in four rural workers are casual labourers, as per the 2022–23 Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS).

- Groundwater irrigation has historically enabled multiple cropping seasons and higher labour demand.

- When wells dry or pumping costs rise, farmers respond by cutting irrigation, shifting to less labour-intensive crops, or reducing cropped area.

- Each of these decisions means fewer hiring days for casual workers, triggering out-migration, underemployment, and wage decline.

Field Evidences

- Purulia and drought-prone districts: Household surveys published in Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change (2024) report sharp declines in casual farm work following groundwater depletion.

- Long-run irrigation data (1996–2020): Research in Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2023) shows that reduced groundwater access significantly lowers agricultural labour demand.

- Marathwada, Vidarbha, Bundelkhand: Multiple studies across Beed, Latur, Dharashiv, Dongargaon, and Jhansi reveal parallel declines in irrigation-based employment.

- At the national level, past gains in rural employment and poverty reduction, once driven by groundwater expansion are being reversed.

- Women face the brunt, with limited non-farm alternatives and rising unpaid water-fetching duties.

- The outcome is deepening food insecurity, debt, and distress migration.

Emerging Solutions: Managing Water, Reviving Work

- Community-Based Groundwater Management: Under the Atal Bhujal Yojana, community-led monitoring, recharge structures, and IoT-enabled piezometers have successfully restored local aquifers.

- These projects not only raise water levels but also create short-term employment, demonstrating a dual win for ecology and livelihoods.

- Smarter Subsidies: Electricity subsidies for pumps encourage over-extraction. Replacing blanket subsidies with metered power and targeted direct transfers would balance conservation with equity, ensuring smallholders are protected without promoting waste.

- Job-Linked Recharge Works: State rural employment programmes can prioritize watershed development and recharge structures in over-exploited blocks.

- Such public works create immediate jobs while improving aquifer health, a direct bridge between water recovery and rural employment.

- Labour-Aware Water Governance: District administrations should integrate groundwater data into employment planning and social protection systems.

- When a block turns ‘critical’, safety nets such as work guarantees, food transfers, and skill programmes need to automatically expand to cushion job losses.

From Hydrology to Human Livelihoods

- Treating groundwater merely as a hydrological statistic blinds policymakers to its social and economic role.

- It is a form of shared capital that sustains millions of informal rural jobs.

- If India aims for resilient rural livelihoods, groundwater must be managed not as a private commodity but as a collective labour asset. The policy choice is clear:

- Act now to revive the invisible employer—or watch rural precarity deepen as wells run dry.

India’s First National Household Income Sample Survey

Context

- India is set to launch its first-ever National Household Income Sample Survey, marking a pivotal shift in how the nation measures poverty and prosperity.

- It aims to present a comprehensive financial balance sheet for Indian households, encompassing all income and expenditure streams.

What the Survey Will Measure

- The survey will collect detailed information on:

- Household incomes and expenditures, across all occupations and community groups.

- Input and output costs of farmers.

- Tax payments, loan burdens, and investment earnings of taxpayers.

- Irregular and multiple income sources for informal workers.

- Monetary valuation of welfare benefits and household assets such as land, homes, and farms.

- By combining these data points, the survey seeks to compute household ‘profits’ and provide a realistic picture of economic well-being at the micro level.

Need for an Income-Based Survey

- India has long relied on household expenditure surveys by the National Statistics Office (NSO) to estimate poverty.

- Expenditure served as a proxy for income, with the last official poverty estimate released in 2012 and the national poverty line updated in 2014.

- Although two more consumption surveys were carried out after 2014, their results were never used to update poverty figures.

- As a result, India currently lacks an official poverty estimate, despite running numerous poverty alleviation schemes.

Data Deficit and Its Implications

- The Household Consumption Expenditure Survey (2022–23) raised expectations for new poverty figures, but none were published officially.

- In the vacuum, independent economists have made their own poverty assessments, findings that remain highly contested.

- Meanwhile, the government has cited a decline in multidimensional poverty, which measures deprivation across areas like health, education, and living standards.

- However, multidimensional poverty is not a substitute for income-based poverty, and it is not recognized in global poverty monitoring standards.

Challenges of Measuring Income

- Income surveys are notoriously difficult to execute while conceptually sound.

- Across countries like the US, China, and Bangladesh, challenges often arise from the sensitivity around income disclosure and the complexity of informal sector earnings.

- India’s earlier attempts from 1955 to 1970 and again in 1983–84 suffered from:

- Underreporting of income due to reluctance and recall errors.

- Difficulty in quantifying non-cash earnings and irregular work patterns.

- Inability to account for returns on investments, rents, or savings interest.

Lessons from the Pre-Test

- The NSO conducted a pre-test in August 2025 before the nationwide rollout. The findings reaffirmed earlier concerns:

- 95% of respondents hesitated to disclose income from various sources.

- A similar proportion of taxpayers refused to reveal their tax information.

- Expenditures were overstated while incomes were understated, often because respondents were unaware of small or irregular earnings like interest and dividends.

- These findings highlight the cultural and methodological barriers to accurate income measurement in India.

Looking Ahead

- India’s decision to pursue a direct income survey in 2024 signals a strong intent to modernize poverty assessment despite repeated setbacks.

- If successful, the initiative could transform policymaking, offering a clearer and more equitable basis for welfare planning.

- However, data reliability remains the key challenge. Unless respondents are encouraged and assured to report truthfully and data collection methods evolve accordingly the survey risks replicating past failures.

Pink Water Lilies in Kuttanad, Kerala

Context

- Surge of vibrant pink water lilies (Omarana Water Lily; Nymphaea × Omarana Bisset) in Kuttanad, Kerala, provides socio-economic benefits, but the plant’s ecological impacts need to be understood.

About Kerala’s Kuttanad Region

- It is often called the ‘Rice Bowl of Kerala’, lies 1–2 meters below sea level, making it India’s lowest altitude region.

- It is spread across Alappuzha, Kottayam, and Pathanamthitta districts, it forms a vital part of the Vembanad Kole Wetland Ecosystem, a Ramsar site.

- It is famous for its ‘below sea level farming’ and recognized by the UN FAO as a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System in 2013.

Ecological Roots of the Bloom of Pink Water Lilies

- The 2018 floods in Kuttanad drastically damaged paddy crops but surprisingly enhanced soil fertility.

- The floodwaters washed away acidic residues and heavy metals, replenished the soil with nutrient-rich silt, and reduced pest populations, creating ideal conditions for both paddy and water lilies.

- Additionally, the Thanneermukkam saltwater barrage, built in the mid-20th century, plays a crucial role.

- It prevents saltwater intrusion into paddy fields, and its delayed opening in recent years has limited the natural ‘salt cleanse’.

- It has allowed aquatic weeds, including water lilies, to flourish unchecked.

Dual Nature of the Water Lily

- Economic and Agronomic Benefits:

- Improving soil quality and nutrient cycling.

- Aiding in phytoremediation, removing heavy metals.

- Controlling noxious weeds such as weedy rice.

- Reducing dependence on broad-spectrum herbicides.

- Environmental Risks (Invasive nature of Nymphaea × omarana):

- Hinders water navigation and blocks sunlight.

- Reduces water quality, affecting fish populations.

- Decomposition releases methane, a potent greenhouse gas.

- Alters biodiversity by attracting new animal species, increasing chemical use for pest control.

- Potential pollination interference with land crops due to increased insect activity.

Towards Sustainable Balance

- To sustain both economic and ecological health, integrated management strategies are essential:

- Eco-friendly control: Mechanical removal during land preparation can help manage overgrowth.

- Biological solutions: A moth caterpillar species that feeds on water lilies shows promise for natural control.

- Optimized barrage operation: Timely opening of the Thanneermukkam barrage to allow periodic saltwater entry could naturally limit proliferation.

- Community engagement: Collaborative governance among farmers, local bodies, and scientists can ensure a balanced approach.

- Continuous monitoring: Long-term studies are needed to assess ecological impacts and prevent outcomes similar to water hyacinth or giant salvinia invasions.

Asian Waterbird Census 2026

Context

- The Asian Waterbird Census (AWC) 2026 has recorded around 9,000 birds belonging to 131 species along the Yamuna floodplains in Delhi.

About the Asian Waterbird Census (AWC)

- It is a long-running, citizen-science–based waterbird monitoring programme conducted annually across Asia and parts of Australasia.

- It focuses on counting waterbirds in wetlands such as rivers, lakes, marshes, floodplains, estuaries, and coastal areas.

Timing & Locations

- The AWC is held every January, coinciding with the peak wintering period for migratory waterbirds.

- Surveys are carried out across South Asia, Southeast Asia, East Asia, and parts of the Middle East, covering thousands of wetlands.

Coordinating Agencies

- The AWC is coordinated internationally by Wetlands International, a global non-profit working on wetland conservation.

- In India, the census is coordinated by the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS), with support from state forest departments, research institutions, and volunteers.

Why is the AWC Important?

- The Asian Waterbird Census plays a critical role in conservation by:

- Tracking long-term population trends of waterbirds;

- Identifying declining species and threatened wetlands;

- Supporting the designation of Ramsar sites (wetlands of international importance);

- Providing data for policy decisions, environmental impact assessments, and conservation planning;

Siau Tagulandang Biaro Islands Regency

Context

- According to Indonesia’s National Disaster Mitigation Agency, the floods in North Sulawesi severely impacted the Siau Tagulandang Biaro Islands Regency.

About Siau Tagulandang Biaro Islands Regency

- It is an island regency located in North Sulawesi, eastern Indonesia.

- It consists primarily of three main islands i.e Siau, Tagulandang, and Biaro, along with several smaller surrounding islands.

- Mount Karangetang, one of Indonesia’s most active volcanoes, is located on Siau Island, making the area geologically vulnerable to natural disasters such as volcanic eruptions, landslides, and flash floods.

- It is particularly prone to natural disasters due to its island geography, limited infrastructure, and high rainfall.

Stingless Bees

Context

- In a landmark move, stingless bees native to the Peruvian Amazon have become the world’s first insects to be granted legal rights.

About Stingless Bees

- They are small, social bees belonging to the tribe Meliponini, primarily in tropical and subtropical regions.

- India hosts more than 30 species of Stingless Bees.

- They are among the most important pollinators in tropical and subtropical ecosystems.

Forever Chemicals: Per and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)

Context

- Recently, France's ban on use of ‘forever chemicals’ in cosmetics and clothing industries came into force.

What are Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)?

- PFAS, aka forever chemicals, are a large family of man-made chemicals that have been used since the 1940s.

- They do not break down easily in the environment or in the human body.

- Their defining feature is a strong carbon–fluorine bond, one of the strongest chemical bonds known. It makes PFAS:

- Highly resistant to heat, oil, stains, and water;

- Extremely persistent in soil, water, wildlife, and people;

Where are PFAS found?

- PFAS have been widely used in everyday and industrial products, such as:

- Non-stick cookware (e.g., older Teflon coatings);

- Water- and stain-resistant fabrics (rain jackets, carpets);

- Food packaging (grease-resistant wrappers, pizza boxes);

- Firefighting foams (especially AFFF used at airports and military bases);

- Cosmetics and personal care products;

- Industrial processes (electronics, metal plating)

Why are PFAS a concern?

- Potential health effects: Increased cholesterol levels, Thyroid disease, Liver damage, Reduced vaccine response in children, Hormonal and immune system disruption, and Increased risk of certain cancers (e.g., kidney, testicular).

- Environmental effects: Long-term contamination of water sources, Bioaccumulation in fish and wildlife, Difficulty and high cost of cleanup.

- Even very low concentrations (parts per trillion) can be concerning.

Can PFAS be removed?

- Activated Carbon (GAC): effective for many PFAS

- Reverse Osmosis (RO): very effective but expensive

- Ion Exchange Resins: increasingly used by utilities

India’s First Urban Night Safari Proposed in Lucknow

Context

- Recently, the Government of Uttar Pradesh unveiled a proposal to establish India’s first urban night safari at the Kukrail Reserve Forest in Lucknow.

Overview of the Night Safari Project

- A First-of-Its-Kind Urban Initiative: The Kukrail night safari aims to promote tourism while offering educational and recreational opportunities to the public.

- It is expected to be developed in multiple phases, expanding gradually while maintaining a balance between tourism and conservation.

- Proposed Features:

- Boosting Eco-Tourism and Employment

- Animal enclosures designed for nocturnal species

- Walking trails and safari routes

- Environmental Concerns:

- Threat to Kukrail’s Ecological Balance: The Kukrail Reserve Forest is a protected green zone and home to diverse flora and fauna, including endangered species of reptiles and birds.

- Construction of enclosures and trails may lead to mass felling of trees

- Artificial lighting and human activity could disturb nocturnal wildlife

- Balancing Development and Conservation:

- Limiting construction to non-core forest zones

- Implementing eco-friendly infrastructure

- Ensuring continuous monitoring of wildlife health and behavior

- Engaging independent environmental experts in the planning process

H5N1 Avian Influenza

Context

- Recently, Kerala confirmed 11 outbreaks of the highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza, leading to the death of 54,100 birds, predominantly ducks.

- The World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) issued an international alert, notifying other member countries about the confirmed outbreaks in Kerala.

Understanding H5N1 Avian Influenza

- H5N1 avian influenza, commonly known as bird flu, is a highly pathogenic viral disease that primarily affects birds.

- It is caused by a strain of the Influenza A virus, belonging to the Orthomyxoviridae family.

Origins and Global Spread

- The H5N1 strain was first identified in 1996 in Geese in China and subsequently spread across Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and Africa.

- Major outbreaks in the early 2000s caused significant losses in the poultry industry, with millions of birds culled to control transmission.

- Periodic resurgences, including recent ones in India, Japan, and parts of Europe, highlight the virus’s persistent threat to both agriculture and public health.

Transmission

- Among Birds: The virus spreads mainly through direct contact with infected birds’ secretions like saliva, nasal fluids, and feces.

- Contaminated feed, water, and equipment can serve as indirect transmission routes.

- Migratory wild birds act as natural reservoirs, facilitating cross-border spread.

- To Humans: Human infections occur rarely, typically through close contact with infected birds or contaminated environments.

- Human-to-human transmission is extremely limited and has not resulted in sustained outbreaks.

Symptoms

- In Birds: Sudden death without prior symptoms; Swelling of the head, comb, and wattles; Drop in egg production; Respiratory distress and loss of appetite;

- In Humans: High fever, cough, sore throat; Conjunctivitis (eye infection); In severe cases, pneumonia and multi-organ failure

- The mortality rate among confirmed human cases exceeds 50%, according to the WHO.

Impact on Economy and Food Security

- H5N1 outbreaks cause mass culling of infected and at-risk birds, leading to:

- Heavy economic losses for poultry farmers

- Disruptions in food supply chains, especially in developing regions

- Reduced consumer confidence in poultry products

- In states like Kerala, India, where duck farming is an important livelihood, outbreaks can significantly affect rural economies and employment.

Prevention and Control

- Biosecurity measures: Regular cleaning, disinfection, and restricted access to poultry farms.

- Vaccination: Used in some countries to limit viral spread.

- Surveillance programs: Early detection and rapid response to suspected cases.

- Public awareness: Educating farmers and handlers about hygiene and early symptom reporting.

Subjective Questions for Practise

Q1. Critically examine India’s Nuclear Power Reforms under the SHANTI Act, 2025. Discuss the objectives of the Act, the key structural and regulatory changes introduced.

Q2. Analyse the provisions of the VB-G RAM G Act, 2025 and assess whether it represents a paradigm shift in rural employment and social security or a dilution of the state’s welfare responsibility.

Q3. Critically analyze the role played by the Supreme Court of India in protecting the Aravalli region through its judgments and directives.

Q4. Discuss how overexploitation of groundwater contributes to a hidden labour crisis. Analyze its social, economic, and environmental impacts.

QUICK LINKS