Down To Earth (01–15 July, 2025)

The following topics are covered in the Down To Earth (01–15 July, 2025):

Debt’s Climate Link: Who Gains From Ballooning Debt?

Context

- As the world grapples with escalating climate crises, a parallel emergency is unfolding in the form of ballooning sovereign debt — especially in developing nations.

About the Debt Trap and Climate Vulnerability

- Developing countries are increasingly caught in a vicious cycle: climate disasters force them to borrow for recovery, and the resulting debt repayments drain resources that could otherwise fund climate resilience.

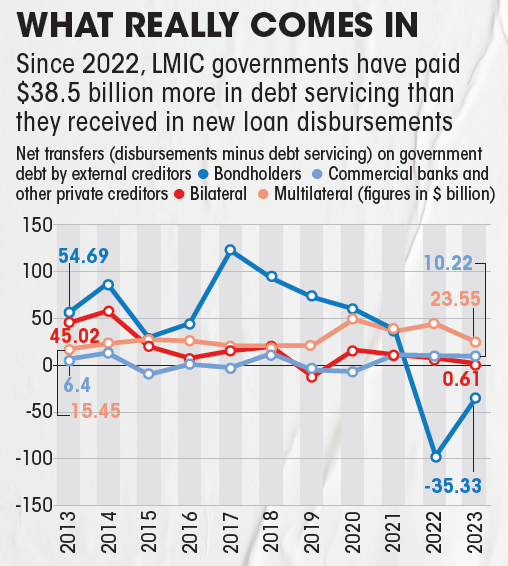

- In 2022–2023 alone, these nations paid $38.5 billion more to external creditors than they received in fresh loans, resulting in a negative net resource transfer.

- This reverse flow of capital — where money moves from the Global South to the Global North — undermines the notion of developed nations as benefactors, and exposes a system where natural resource revenues, such as oil and copper, are tied to debt servicing, perpetuating environmental degradation and economic dependency.

- Chad owes $1.45 billion to Swiss oil giant Glencore, with repayments tied to oil exports.

- Zambia defaulted in 2020 and now channels copper revenues to repay a $1.5 billion debt to Glencore.

How large is sovereign debt?

Climate Finance or Financial Colonialism

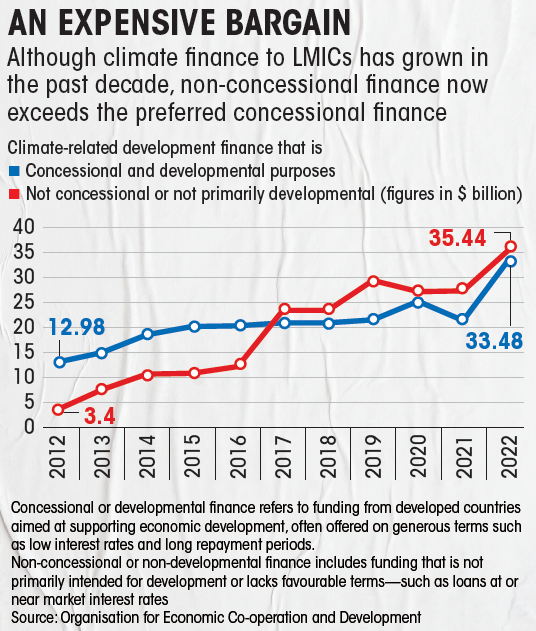

- While climate finance is touted as a solution, over 70% of public climate finance is debt-based, primarily focused on mitigation rather than adaptation.

- It burdens vulnerable nations with loans instead of grants, limiting their fiscal space and deepening inequality.

- The Fourth International Conference on Financing for Development (FfD4) in Seville spotlighted these issues, but critics argue that without structural reform of the global financial architecture, climate finance risks becoming a tool of financial colonialism.

Call for Justice and Reform

- Debt-for-nature swaps that prioritize conservation over extraction;

- Multilateral frameworks for sovereign debt restructuring;

- Grant-based climate finance tailored to the needs of low-income countries

Rising Sovereign Debt in Developing World

Context

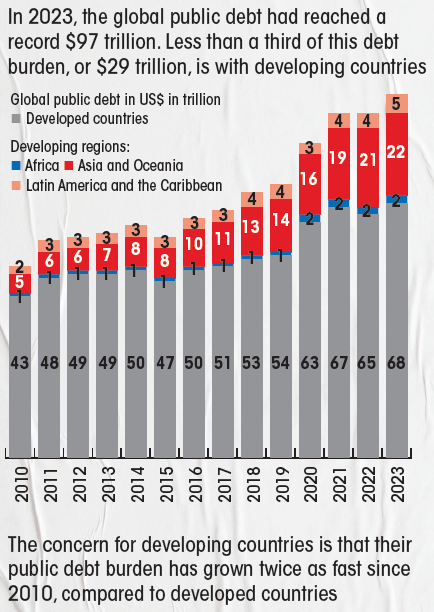

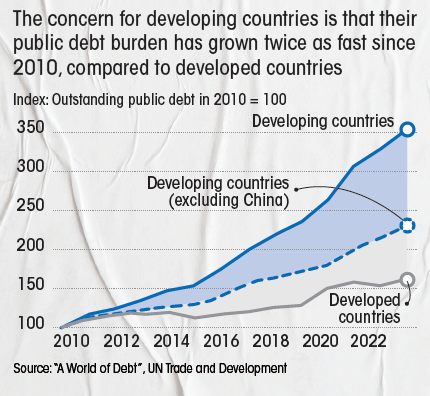

- As climate disasters intensify and global financial systems remain skewed, sovereign debt in developing countries is surging — posing a grave threat to both economic stability and climate resilience.

Historical Debt Trap

- The origins of today’s debt crisis trace back to the 1970s oil shocks, when oil-importing developing nations faced soaring energy bills. Western banks, flush with ‘petrodollars’, began lending aggressively to these countries.

- By 1982, private banks were disbursing $63 billion annually, nearly double the amount from official sources.

- Countries like Brazil paid $176 billion in interest on a $124 billion debt between 1972 and 1988— highlighting how debt servicing outpaced economic growth.

Modern-Day Drivers of Debt

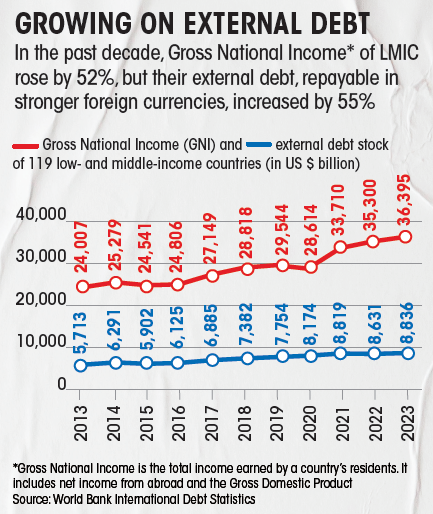

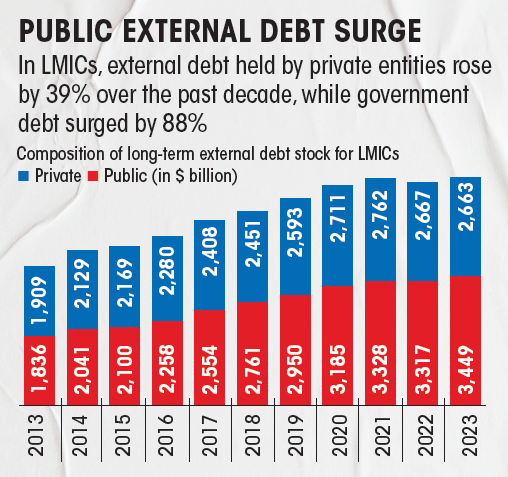

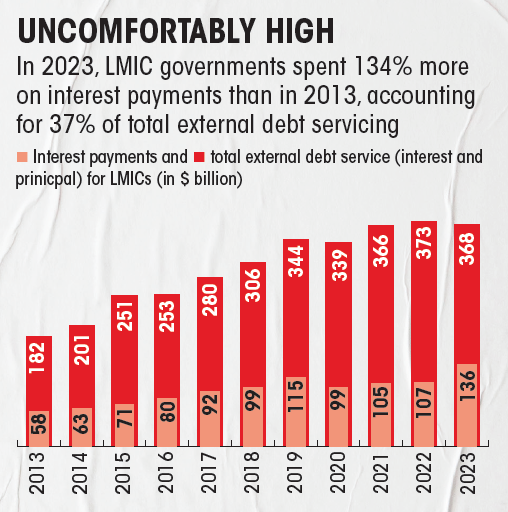

- Developing nations spent $1.4 trillion on foreign debt servicing in 2023—an all-time high.

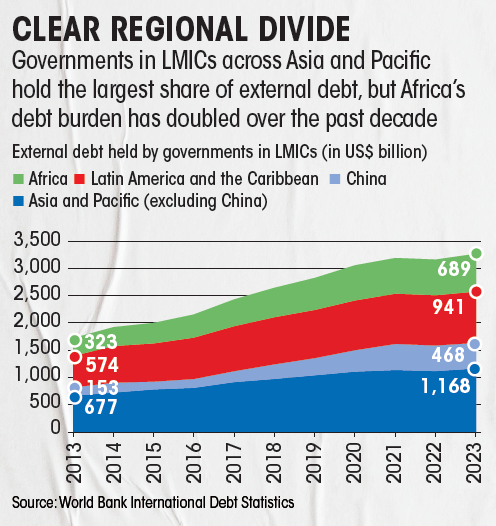

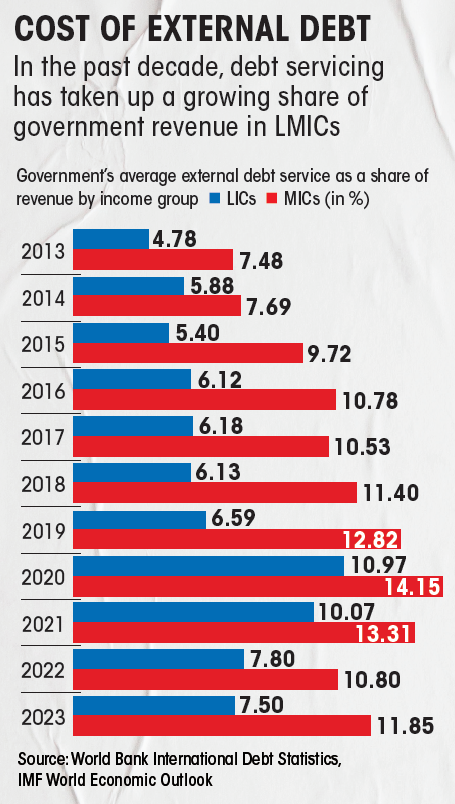

- Over 54 countries allocated 10% or more of government revenues to interest payments, with nearly half in Africa.

- For every dollar of gross national income (GNI), developing economies spent 2.5 cents on external debt servicing in 2023, up from 1.6 cents in 2013.

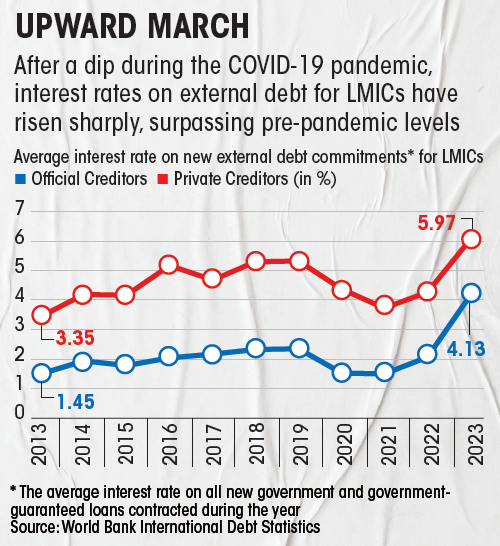

- It is fueled by climate disasters, pandemic recovery costs, and rising global interest rates, which have made borrowing more expensive and repayment more difficult.

Biased Credit Ratings and Unfair Interest Rates

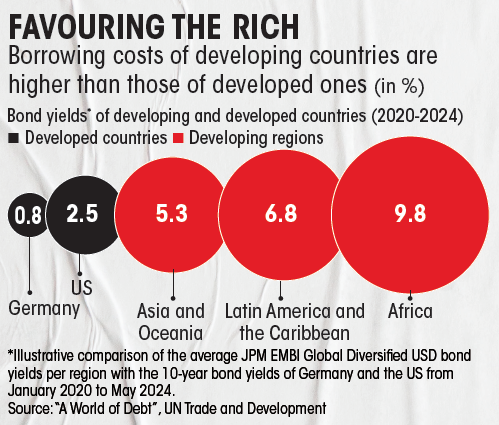

- Developing countries face interest rates 2–12 times higher than those of wealthy nations like the U.S. and Germany.

- Sovereign credit ratings — meant to assess repayment ability—are often negatively biased against the Global South.

- Cameroon and Ethiopia saw their ratings downgraded after seeking relief under the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), increasing their borrowing costs.

- A UNDP report estimated that Africa lost $24 billion in excess interest and $46 billion in forgone lending due to unfair ratings.

Why is sovereign debt rising in developing countries?

- According to the World Bank’s ‘International Debt Report’, developing countries spent a record $1.4 trillion to service their foreign debt as their interest costs climbed to a 20-year high in 2023.

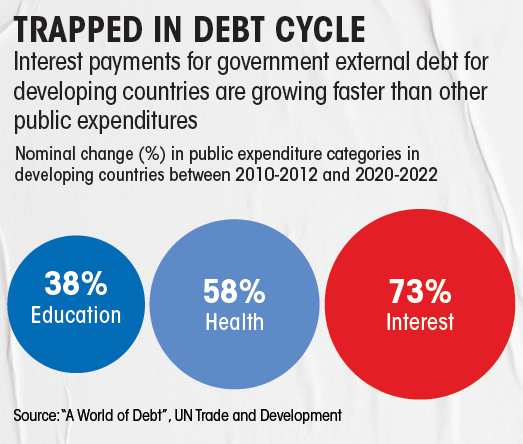

- According to the UNCTAD’s ‘A World of Debt’ Report, the rising pressure of interest payments is substantial across regions, particularly in Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean.

What are the spillover impacts of external debt?

Climate Finance vs. Debt Burden

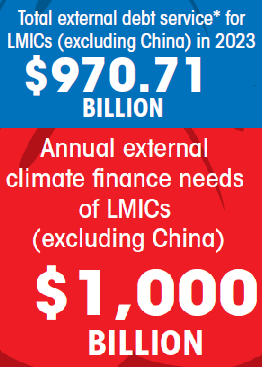

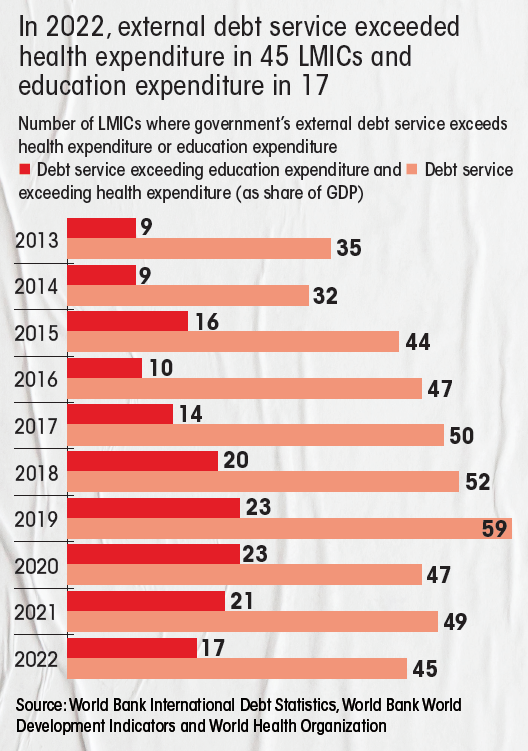

- Ironically, many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) now spend more on debt payments than on climate goals.

- In 2023, LMICs paid $368 billion in external debt service—double the amount from a decade earlier.

- It undermines global climate targets, as countries cannot invest in adaptation or mitigation while servicing ballooning debts.

Way Forward

- Debt restructuring and debt-for-nature swaps;

- Grant-based climate finance instead of loans;

- Reforming the global financial architecture to ensure fair access and ratings.

National Character of Indian Science

Context

- The national character of Indian science is marked by a curious contradiction: a deep pride in rising patent numbers and global ambitions, juxtaposed with a lack of cutting-edge innovation and introspection.

Patent Fever vs. Innovation Drought

- India has celebrated a dramatic rise in patent applications — over 100,000 patents granted in 2023–24, nearly triple the previous year. It is hailed as proof of scientific prowess.

Historical Echoes: Al-Biruni’s Critique

- A striking parallel comes from the 11th-century scholar Al-Biruni, who spent 13 years studying Indian science. He praised Indian mathematicians and astronomers but also noted a tendency toward intellectual insularity.

- In his Kitab al-Hind, he wrote, ‘The Hindus believe that there is no country but theirs, no science like theirs… If they travelled and mixed with other nations, they would soon change their mind’.

- It resonates today, as India’s scientific narrative often leans toward nationalistic pride rather than global collaboration or critical self-assessment.

Global Leadership Aspirations

- The Bharat 6G Alliance even aims to contribute 10% of global 6G patents.

- India’s ambition to lead in 6G technology — despite lagging in 5G deployment — is emblematic of this paradox.

- While China has already established key 6G standards through the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), India is still catching up.

Science and Secularism

- Indian science has historically coexisted with religiosity.

- Institutions like the Indian Institute of Astrophysics (IIA) and CSIR’s Central Building Research Institute (CBRI) have contributed to projects like the Surya Tilak in Ayodhya, blending optics and astronomy with religious symbolism.

Way Forward

- Evaluate the impact of patents beyond numbers

- Invest in basic research and institutional capacity

- Foster global collaboration and critical thinking

- Balance pride with humility, as Al-Biruni suggested

Strengthening Wildlife Protection Laws in India

Context

- Despite being a signatory to international conventions and having robust domestic laws like the Wild Life (Protection) Act (WLPA), 1972, enforcement gaps and legal loopholes persist in India.

Illegal Wildlife Trade: A Rising Crisis

- Wildlife hunting in India has transformed from a traditional subsistence activity into a commercialized black market driven by demand for exotic pets, meat, medicine, and ornaments.

- Recent incidents, such as the smuggling of over 50 reptiles including spider-tailed horned vipers and Asian leaf turtles at Mumbai airport, underscore the sophistication of trafficking networks.

- These species are protected under Schedule IV of WLPA and Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES).

Case Study: Pangolin Plight

- Indian pangolins, listed in Schedule I of WLPA and Appendix I of CITES, face severe threats due to illegal demand for their meat and scales.

- TRAFFIC India reported the seizure of 5,772 pangolins between 2009 and 2017, despite a blanket ban.

- The IUCN estimates up to a 90% population decline over three generations—a sharp warning of impending extinction.

Vulnerable Species in the Trade Web

- Species frequently targeted include:

- Mammals: Slender loris, macaques, bats

- Birds: Parakeets, grey parrots

- Reptiles: Spiny-tailed lizards, Indian softshell turtles

- This illegal trade not only threatens biodiversity but also heightens the risk of zoonotic spillovers, as seen in outbreaks of Ebola, M-pox, and possibly COVID-19.

Existing Legal Frameworks

- India’s wildlife protection relies primarily on:

- Wild Life (Protection) Act, 1972

- Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980

- Environmental (Protection) Act, 1986

- Of these, only the WLPA directly addresses hunting and trade. Amendments in 2022 have aligned WLPA with CITES, regulating trade in endangered species.

Recommendations: Strengthening Legal Frameworks

- Integrate Wildlife Crimes Across Laws:

- Customs Act, 1962: Should clearly define ‘exhaustible natural resources’ and include specific references to WLPA species.

- Biological Diversity Act, 2002 & Foreign Trade (Development Regulation) Act, 1992: Must explicitly ban the import/export of WLPA- and CITES-listed species, including vectors of zoonoses.

- Ban Exotic Pets and Wildlife in Shops:

- Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, 1960 & Pet Shop Rules, 2018: Should prohibit trade or display of WLPA/CITES/IUCN-listed species.

- Exotic animals like Aldabra tortoises, African pythons, and capuchin monkeys have been found in pet shops, revealing gaps in the current rules.

- Regulate Wild Meat Sales:

- Food Safety and Standards Act (FSSA), 2006: Should ban sale and consumption of wild animal meat, a key driver of poaching.

- The Arms Act, 1959 should be revised to mention wildlife and ban the use of firearms and weapons in hunting.

- Include Wildlife Protection in Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita: The new penal code must incorporate offences like trapping, baiting, or maiming wildlife with tools and weapons as punishable crimes.

Community-Based Conservation Measures

- Monitor Rural Wildlife Trade: Village haats and weekly markets often host the sale of illegally hunted animals and derivatives. Local communities can serve as the first line of defense through:

- Monitoring and reporting illegal sales

- Assisting forest officials in market surveillance

- Provide Livelihood Alternatives: Creating sustainable employment—such as eco-tourism, forest produce marketing, or handicrafts—can disincentivize hunting among forest-dwelling communities.

- Enforce Market Regulations: Animal Markets Rules, 2018 should be extended to include wild animals.

- Imposing strict penalties on the sale of bushmeat and wildlife products in these markets is crucial.

Conclusion

- India needs to act decisively to integrate, update, and enforce wildlife protection laws while simultaneously investing in community partnerships.

- By closing legislative loopholes and addressing ground realities, the country can better safeguard its invaluable biodiversity and prevent future ecological and health crises.

Supreme Court Recognises Oran Lands as Forests

Context

- Recently, the Supreme Court of India , in the case T N Godavarman Thirumulpad vs Union of India, recognized Oran lands — sacred groves traditionally protected by communities in Rajasthan — as ‘forests’ under the Forest Conservation Act (FCA), 1980.

What Are Orans?

- Orans are community-managed sacred groves, often dating back to pre-agrarian societies, representing a spiritual and ecological heritage.

- In Rajasthan, approximately 25,000 Orans span 0.6 million hectares, serving not only as spiritual sites but also as critical ecosystems.

- They support grazing, natural water filtration, livelihood generation, and biodiversity preservation.

Cultural and Ecological Importance

- Cultural Roots: Orans reflect the deep-rooted symbiotic relationships between communities and nature.

- Ecological Services: They help recharge aquifers, sustain natural springs, and act as buffers against climate shocks.

- Livelihoods: Orans support livestock-based economies and provide forest produce vital to local livelihoods.

Legal Misclassification and Recent Threats

- Historically, Orans were misclassified as wastelands in revenue records. This allowed for their diversion to developmental projects, including renewable energy installations in eastern Rajasthan.

New Directions Under Wildlife and Forest Rights Laws

- Declaration of Orans as Community Reserves under the Wild Life Protection Act, 1972.

- Protection under the Forest Rights Act (FRA), 2006, allowing local communities the right to conserve and manage Community Forest Resources (CFRs).

Challenges in FRA Implementation

- Despite legal provisions, the implementation of CFR rights remains weak:

- Only 48.95% of claims under FRA have been granted.

- Rajasthan has issued just 3,000 titles out of 5,000 claims.

- States like Kerala, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Tamil Nadu, and others have not granted any CFR rights.

- Forest departments often resist community claims, undermining FRA’s core principles.

Community Stewardship vs Bureaucratic Control

- Orans demonstrate effective community-led natural resource management.

- However, formal recognition often brings top-down bureaucratic hurdles, diluting community control. For conservation efforts to be meaningful, there must be a balance between legal formalisation and community autonomy.

Urgency of Bottom-Up Conservation

- Between 2008-09 and 2022-23, over 17,000 forest diversion projects involving 0.3 million hectares were approved under FCA. Such trends threaten ecosystems like Orans unless community-driven, bottom-up frameworks are prioritised.

Conclusion: A Paradigm Shift in Forest Governance

- The Supreme Court’s judgement is a watershed moment in recognising community-centric conservation.

- Its success now hinges on effective ground-level implementation, community participation, and harmonisation of traditional wisdom with legal protection.

Rethinking India’s Poverty Metrics

Context

- India’s last official poverty estimate was conducted using the 2011-12 consumption expenditure survey.

- Since then, there has been no governmentreleased update, leaving a data vacuum on the nation’s actual poverty levels.

About

- India’s poverty estimates are now based on the 2023 Consumption Expenditure Survey, which adopted a revised methodology.

- The World Bank’s updated global poverty line suggests a dramatic decline in extreme poverty— from 27.1% in 2011–12 to 5.3% in 2024.

- The new global poverty line — $3 per person per day (based on 2021 purchasing power parity; earlier at $2.15) — is based on the median national poverty line of 23 low-income countries, including Burkina Faso, where two-thirds of the population live below it.

India’s Poverty Decline in Numbers

- Poverty in India dropped from 27.1% (2011-12) to 5.3% (2022-23). It implies that 171 million people have exited extreme poverty in a decade.

- As of 2024, 54.6 million Indians still live on less than $3/day.

- India’s decline has skewed global poverty figures, making South Asia the only region to show improvement.

India’s Global Impact

- India’s reduction in poverty significantly affects global statistics. Despite the rise in the global poor— from 713 million to 838 million under the new threshold—South Asia was the only region to record a decline, driven entirely by India.

- It underscores India's outsized influence in global poverty trends, being home to the largest absolute number of poor people.

Methodological Concerns

- No official national poverty line update since 2011– 12.

- Individual economists have used the new survey to claim unprecedented poverty reduction, but these estimates remain unacknowledged by the Union government.

- The government now relies on multidimensional poverty data from NITI Aayog, which measures deprivation rather than income.

Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB)

Context

- Farmers across the European Union are voicing growing concern over Mercosur bloc and Ukraine for influx of cheap agricultural imports.

About CPCB

- It is a statutory body under the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, established in 1974 under the Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act.

- It was later entrusted with responsibilities under the Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1981, and the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986.

Core Functions

- Water & Air Quality Monitoring: CPCB operates nationwide networks to monitor pollution levels in rivers, lakes, and urban air.

- Standard Setting: Develops environmental standards for industries, waste management, and emissions.

- Technical Advisory: Provides scientific input to the central government and coordinates with State Pollution Control Boards (SPCBs).

- Legal Enforcement: Issues directions under environmental laws and supports litigation in pollution-related cases.

- Public Awareness & Training: Organizes campaigns, publishes reports, and trains stakeholders in pollution control practices.

Monitoring Programs

- National Air Quality Monitoring Programme (NAMP): Tracks pollutants like SO₂, NO₂, PM10 across 262 cities.

- Water Quality Network: Covers 200 rivers, 60 lakes, and 321 groundwater stations under programs like MINARS and GEMS.

Recent Initiatives by CPCB

- Revised Industrial Classification (2025): Introduced the ‘Classification-2025’ framework to reclassify 419 industrial sectors based on updated Pollution Index (PI) scores.

- Added a new Blue Category for essential environmental services like Compressed Biogas (CBG) plants and biomining operations.

- It helps streamline regulatory oversight and tailor pollution control measures more effectively.

- Digital Tools & Public Engagement: Launched the Sameer App for real-time air quality updates, empowering citizens to monitor pollution levels.

- Released a Compendium of Eco-Alternatives to banned single-use plastics, promoting sustainable consumption.

- Eco-City Program: Expanded the Eco-City initiative to improve urban environments through better waste management, green infrastructure, and pollution control.

- Environmental Monitoring & Capacity Building: Strengthened national networks for air and water quality monitoring across 800+ stations.

- Rolled out new guidelines for recognizing environmental laboratories, enhancing scientific rigor in pollution assessment.

- Support for Sustainable Products: Implemented the Ecomark Scheme under the LiFE (Lifestyle for Environment) mission to certify eco-friendly products in partnership with the Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS).

Major Challenges Faced by CPCB

- Severe Staff Shortages: Over 50% of sanctioned posts in CPCB and State Pollution Control Boards (SPCBs) are vacant.

- States like Bihar and Jharkhand report vacancy rates of over 70%, crippling enforcement and monitoring capacity.

- Short tenures of Chairpersons and Member Secretaries hinder long-term planning.

- Inadequate Funding: CPCB is heavily reliant on government grants, with limited autonomy to raise funds.

- Budget constraints affect pollution monitoring infrastructure, research, and public outreach.

- Limited Technical Capacity: Many staff lack specialized training in environmental science and pollution control technologies.

- CPCB struggles to keep pace with emerging pollutants and complex industrial processes.

- Weak Coordination with SPCBs: CPCB and SPCBs often operate in silos, leading to inconsistent enforcement across states.

- Weak Coordination with SPCBs: CPCB and SPCBs often operate in silos, leading to inconsistent enforcement across states.

- Judicial Overreach & Policy Gaps: Courts sometimes bypass CPCB’s authority, creating tension between legal and executive mandates.

- Amendments to laws like the Water Act have sparked concerns over diluted enforcement powers.

- Transparency & Reporting Issues: CPCB’s annual reports haven’t been publicly available since 2020– 21, raising concerns about accountability.

- Data gaps hinder informed policymaking and public trust.

- Infrastructure Deficiencies: Monitoring stations are unevenly distributed and often outdated.

- Satellite and real-time data integration is still in early stages.

Construction and Demolition (C&D) Waste Rules 2025

Context

- Recently, the government has introduced the Construction and Demolition (C&D) Waste Rules 2025 to manage India’s construction waste.

About the C&D Waste

- India generates more than 150 million tonnes of C&D waste annually—but only a fraction is processed.

- C&D Waste Rules (2025) are the revised rules, building upon the foundation laid in 2016, seek to tighten oversight and streamline the reuse of construction debris.

- The Rules will come into force from April 1, 2026.

Key Features of C&D Waste Rules (2025)

- It makes bulk C&D waste generators or producers responsible for recycling and reuse of the waste.

- Mandatory waste segregation at source for projects over 300 square meters;

- GPS tracking of C&D waste vehicles to monitor disposal and prevent illegal dumping;

- Incentives for recycled materials, including tax benefits for use in infrastructure projects;

- Penalties for non-compliance, with stricter enforcement mechanisms and fines;

Why Do Building Codes Need a Revision?

- Lack of mandatory use of recycled aggregates in structural applications

- No national standard for eco-friendly demolition practices

- Limited integration of lifecycle assessments in design approvals

- Inadequate push for deconstruction over demolition

Urgency of Circular Construction

- Market skepticism around recycled products

- Logistical hurdles in waste transport

- Absence of procurement mandates in public works

Toward a Sustainable Future

- Amending building codes to mandate recycled content in concrete, bricks, and road base layers

- Training architects and engineers in green construction practices

- Public procurement policies favoring eco-friendly designs

- Incentivizing deconstruction methods that allow material recovery

Global Hunger Hotspots

Context

- Recently, the FAO and WFP of the United Nations identified 18 hunger hotspots in 22 countries because of convergence of armed conflict, climate shocks, economic instability, and displacement.

Hotspots of Highest Concern

- According to the FAO-WFP Hunger Hotspots Report, five regions are at ‘highest concern’ due to catastrophic hunger levels and imminent risk of famine:

- Sudan

- South Sudan

- Burkina Faso

- Haiti

- Mali

- Sudan, South Sudan, and Burkina Faso, are in Africa, are experiencing acute food insecurity driven by internal conflict, population displacement, and disrupted agricultural systems.

Drivers of Hunger

- Conflict: Armed violence is the leading cause of food insecurity in 12 of the 13 most critical hotspots.

- Climate Extremes: Floods, droughts, and erratic rainfall are devastating crops and livelihoods, especially in South Sudan and Haiti.

- Economic Shocks: Inflation, currency collapse, and trade disruptions are reducing purchasing power and access to food across regions.

Funding Shortfalls and Access Constraints

- Despite the urgency, humanitarian operations are severely underfunded. The UN estimates $12.2 billion is needed for food aid, but only 9% has been secured.

- Aid delivery is also hampered by security risks, bureaucratic barriers, and damaged infrastructure, leaving millions without assistance.

A Call to Global Action

- UN leaders have issued a ‘red alert’, urging the international community to:

- Scale up emergency food assistance;

- Invest in resilient agriculture and local food systems;

- Advocate for peacebuilding and conflict resolution;

- Ensure unrestricted humanitarian access

Guidelines on Disposal of Expired And Unused Medicines

Context

- Recently, the Central Drugs Standard Control Organization (CDSCO), India’s drug regulator, has released new guidelines for the safe disposal of expired and unused medicines.

Key Features of the New Guidelines

- It introduces a ‘Flush List’ for specific potent opioids, recommending they be flushed to prevent poisoning.

- It promotes environmentally sound methods such as encapsulation, inertisation and incineration.

- Segregation at Source: Pharmacies, hospitals, and households need to separate expired and unused medicines from general waste.

- Return-to-Pharmacy Programs: Consumers are encouraged to return unused drugs to designated collection centers.

- Prohibited Disposal Methods: Flushing medicines down toilets or drains is strictly discouraged.

- Authorized Disposal Channels: Only licensed biomedical waste handlers can incinerate or chemically neutralize pharmaceutical waste.

- Labeling Requirements: Expired medicines must be clearly marked and stored in tamper-proof containers before disposal.

Why Disposal Guidelines Matter?

- India generates thousands of tonnes of pharmaceutical waste annually, much of which ends up in landfills, water bodies, or is burned—posing serious risks to ecosystems and human health.

- Antibiotics, painkillers, and hormonal drugs leach into soil and water, contributing to antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and contaminating food chains.

- Improper disposal has led to trace pharmaceuticals in groundwater, affecting aquatic life and potentially entering drinking water supplies.

What’s Next?

- Public awareness campaigns to educate consumers;

- Training for pharmacists and healthcare workers;

- Integration with Swachh Bharat and AMR strategies;

- Digital tracking systems for pharmaceutical waste

Capping Mgnregs Spending

Context

- Recently, the government considered budgetary caps on the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS).

About the MGNREGS

- It guarantees 100 days of wage employment to rural households, and in tribal regions, it often serves as the primary source of income during lean agricultural seasons.

- Tribal populations — especially in forested and remote areas — depend on the scheme for wages, food security, debt reduction, and social empowerment.

- In states like Jharkhand, Odisha, Chhattisgarh, and Madhya Pradesh, tribal workers make up a significant share of MGNREGS beneficiaries.

- The scheme supports community assets like water harvesting structures and forest paths, which are vital for tribal livelihoods.

Budget Caps

- Reduced work availability, forcing tribal families to migrate or fall into poverty;

- Delayed wage payments, which already plague the system and disproportionately affect marginalized groups;

- Exclusion from planning and implementation, as tribal voices are often underrepresented in local governance.

Way Forward

- Strengthening implementation through timely payments and better transparency;

- Expanding work types to include forest-based activities and ecological restoration;

- Ensuring tribal participation in planning and monitoring processes.

Banks Pledged $869BN to Fossil Fuel Firms in 2024

Context

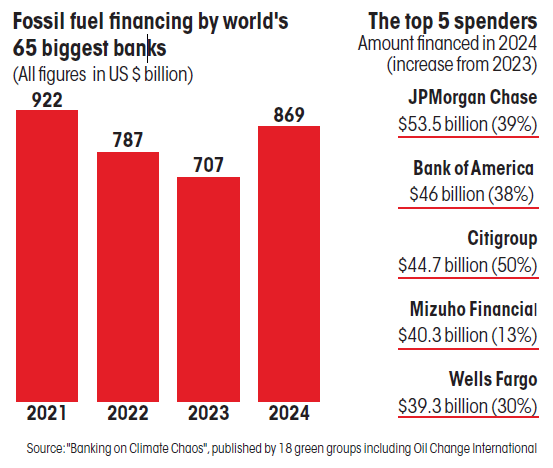

- According to a report, the world’s biggest banks poured a staggering $869 billion into fossil fuel companies in 2024, despite mounting climate warnings and global net-zero commitments.

Scale of Fossil Fuel Financing

- The report reveals that 60 of the world’s largest banks continued to fund oil, gas, and coal projects at near pre-pandemic levels.

- It includes financing for exploration, extraction, pipeline construction, and liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals.

- Top financiers include JPMorgan Chase, Citi, Bank of America, and Barclays.

- $142 billion went to companies expanding fossil fuel operations, directly contradicting climate pledges made under the Paris Agreement.

Regional Breakdown

- North American banks accounted for nearly half of the total fossil fuel financing.

- European banks, while reducing coal exposure, increased funding for LNG and offshore oil.

- Asian banks, particularly in China and Japan, ramped up support for coal-fired power and mining.

Calls for Accountability

- Mandatory climate disclosures and stress tests for fossil fuel exposure;

- Divestment campaigns targeting pension funds and institutional investors;

- Policy reforms to align banking practices with national climate goals

Green India Mission (2021-30)

Context

- Recently, the MoEF&CC has released a revised Green India Mission (2021-30), focusing on restoring vulnerable landscapes such as the Aravallis, Western Ghats, and the Indian Himalayan region.

Objectives of Green India Mission (2021–2030)

- To increase forest and tree cover to create a carbon sink of 3.39 billion tonnes, adopting a microecosystem approach.

- Increase forest/tree cover on 5 million hectares of forest and non-forest land.

- Enhance ecosystem services, including biodiversity, hydrology, and carbon sequestration.

- Boost livelihoods for 3 million forest-dependent households.

- Achieve annual CO₂ sequestration of 50–60 million tonnes by 2030.

Strategic Shifts in the 2021–30 Framework

- Aravallis and Western Ghats;

- Mangroves and Himalayan regions;

- Arid zones and degraded grasslands

Sub-Missions Driving Impact

- Enhanced Forest Quality and Ecosystem Services:

- Restoration of open forests and degraded ecosystems;

- Biodiversity conservation and hydrological improvements;

- Increase in Forest and Tree Cover:

- Afforestation in scrublands, ravines, and urban areas;

- Agroforestry and social forestry expansion

- Livelihood Diversification for Forest Communities:

- Skill development and income generation;

- Promotion of sustainable forest-based enterprises;

Implementation & Monitoring

- Joint Forest Management Committees (JFMCs) will lead local execution;

- GIS-based monitoring and National Afforestation Dashboard will track progress;

- Third-party audits and social audits ensure transparency;

- Integrated Nursery and Research Centres will supply quality planting stock.

Ground-Level Ozone

Context

- Recently, the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) revealed that ground-level ozone breached national safety limits nearly every day in the National Capital Region (NCR) between March and May 2025.

About the Ground-Level Ozone

- It is often dubbed the ‘bad ozone’, is a secondary pollutant formed when oxides of nitrogen (NOₓ) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) react in the presence of sunlight.

- High temperatures and stagnant air exacerbate ozone formation, especially in densely populated urban areas.

- It is a toxic component of urban smog — posing serious risks to human health and ecosystems, unlike stratospheric ozone, which shields us from harmful UV rays.

- Major Sources: Vehicle emissions; Industrial processes; Petrol pumps and solvent use; Biomass and waste burning.

Health and Environmental Impacts

- Respiratory distress: Coughing, throat irritation, and reduced lung function;

- Aggravation of chronic diseases: Asthma, bronchitis, and heart conditions;

- Long-term exposure: May cause permanent lung damage and increased sensitivity to allergens

Government Measures

- BS-VI Vehicle Norms: Reduced NOₓ emissions by up to 85% in heavy-duty vehicles.

- Electric Mobility Push: Under PM-E Drive, promoting zero-emission transport.

- Industrial Emission Standards: Revised for sectors like pharmaceuticals, paint, and thermal power.

- Vapour Recovery Systems (VRS): Installed at petrol pumps to reduce VOC emissions.

- National Clean Air Programme (NCAP): Targets 130 non-attainment cities with city-specific action plans.

A980: Extreme Helium (Ehe) Star

Context

- Recently, the Scientists at the Indian Institute of Astrophysics (IIA), Bengaluru, have identified a rare Extreme Helium (EHe) star named A980—located in the constellation Ophiuchus, 25,800 light-years away.

About A980 (EHe Stars)

- It was discovered by IIA, Bengaluru using the Hanle Echelle Spectrograph on the Himalayan Chandra Telescope.

- It was initially thought to be a hydrogen-deficient carbon star, but its spectral fingerprint revealed that it is singly-ionized germanium (Ge II)—a metallic element never before detected in EHe stars.

- Germanium abundance in A980 is eight times higher than in the Sun;

- First-ever detection of Ge II lines in an EHe star’s optical spectrum;

- Suggests active s-process nucleosynthesis, where atomic nuclei slowly capture neutrons to form heavier elements;

How Do EHe Stars Form?

- EHe stars are incredibly rare — only a few dozen have been identified. They are believed to form through the merger of two white dwarfs:

- One carbon-oxygen white dwarf;

- One helium-rich white dwarf

Draft Guidelines for Discarded Solar PV Modules

Context

- Recently, the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) released draft guidelines for safe storage, handling and transport of discarded solar PV

modules. - It was issued under the E-Waste Rules, 2022, they aim to manage rising solar waste as India’s installed solar capacity crosses 110 GW.

Why Solar Waste Needs Urgent Attention?

- India is projected to generate over 1.8 million tonnes of solar waste by 2030, as installations from the past decade begin to reach their end-of-life.

- These modules — containing glass, silicon, metals, and toxic materials — pose risks to soil, water, and public health, without proper disposal mechanisms.

Key Provisions in the Draft Guidelines

- Mandatory Registration: Manufacturers and producers must register on a centralized portal and maintain inventory of solar PV waste.

- Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR): Producers are accountable for collecting and recycling discarded modules through authorized channels.

- Storage Protocols: Waste must be stored safely until 2034–35, following standards set by the CPCB.

- Annual Returns: Entities must file annual reports detailing waste generation and disposal practices.

- Certified Recyclers: Only licensed recyclers can process solar waste, with mandated recovery of materials like glass, silver, and silicon.

Challenges Ahead

- Lack of infrastructure for large-scale recycling;

- Low awareness among consumers and installers;

- High cost of recycling compared to landfilling;

- Need for clear standards on recycled material use in new modules

Research and Innovation Push

- MNRE has identified solar PV recycling as a priority under its RE-RTD (Renewable Energy Research and Technology Development) program.

- Several research proposals have been received to develop cost-effective recycling technologies and recover critical materials.

Toward a Greener Solar Future

- Incentivize recycling through tax benefits and procurement mandates;

- Build regional recycling hubs and logistics networks;

- Promote eco-design and modular panels for easier disassembly

Un Ocean Conference (Unoc)

Context

- Recently, the third United Nations Ocean Conference (UNOC3), held in Nice, France, to address the urgent need for ocean conservation.

About the UN Ocean Conference (UNOC)

- It is a high-level global summit aimed at accelerating action to conserve and sustainably use the ocean, in line with Sustainable Development Goal 14 (SDG 14).

Purpose and Goals

- Supports implementation of SDG 14, which focuses on protecting marine ecosystems, reducing pollution, and promoting sustainable fisheries.

- Mobilizes governments, civil society, scientists, Indigenous communities, and the private sector to address ocean-related challenges.

- Encourages voluntary commitments, policy frameworks, and partnerships to restore ocean health.

Key Themes

- High Seas Treaty: 50 ratifications so far, nearing the 60 needed for enforcement.

- Marine Protected Areas: Countries like French Polynesia pledged vast new reserves (world’s largest marine protected area).

- Deep-Sea Mining: Macron’s declaration ‘the abyss is not for sale’ echoed calls for a moratorium.

- Coral Reefs & Biodiversity: New pledges and funding to protect climate-resilient reefs.

Key Pledges At UNOC3

- Adoption of the Nice Ocean Action Plan, titled ‘Our Ocean, Our Future: United for Urgent Action’.

- European Commission: €1 billion for ocean conservation and sustainable fishing.

- Germany: €100 million for clearing underwater munitions.

- Indonesia & World Bank: Launch of a Coral Bond to fund reef conservation.

Funding Challenges

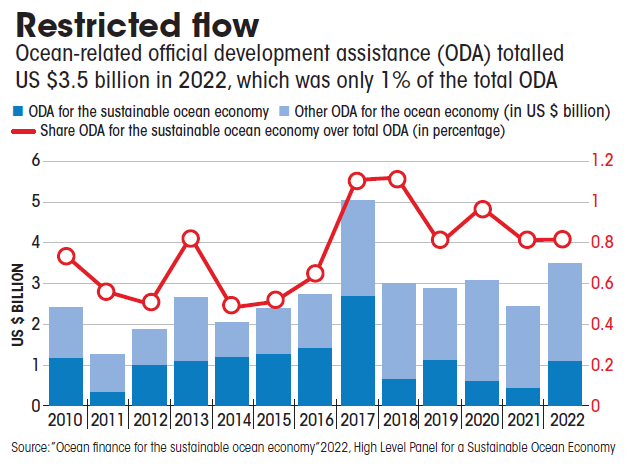

- SDG 14 is the least funded of all global goals, needing $175 billion annually by 2030.

- The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework’s 30x30 target — protecting 30% of marine and coastal areas by 2030—also faces a $14.6 billion annual shortfall.

- Despite pledges, actual funding remains far below targets.

- Innovative finance tools like blue bonds, debt-fornature swaps, and parametric insurance were discussed, but concerns persist over scalability and equity.

Looking Ahead

- The next UN Ocean Conference is scheduled for 2028, co-hosted by Chile and South Korea.

- With the 2030 deadline approaching, the pressure is on to turn pledges into real-world impact.

Global Fund for Coral Reefs (Gfcr)

Context

- The urgency of the Global Fund for Coral Reefs has grown in light of recent mass bleaching events and alarming biodiversity losses.

About the GFCR

- It was launched in 2020, as the world’s first blended finance instrument dedicated exclusively to coral reef conservation.

- It aims to leverage up to $3 billion in public and private finance by 2030 to protect at least 3 million hectares of coral reefs globally.

- It operates through two mechanisms:

- UN Grant Fund: Provides catalytic funding for reef-positive initiatives.

- Equity Investment Fund: Supports sustainable businesses that benefit reef ecosystems.

Recent Funding

- $25 million in new grants for resilience efforts across 23 nations.

- Egyptian Red Sea Initiative: A landmark blended finance program aiming to mobilize $50 million for reef conservation.

- New Zealand’s $10 million pledge at COP16, setting a precedent for donor engagement.

Concerns

- According to the Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network, 14% of the world’s coral reefs were lost between 2009 and 2018, an area larger than the Great Barrier Reef.

- In 2024, the fourth global mass bleaching event was declared, with 80% of reefs worldwide experiencing severe stress due to rising ocean temperatures.

- These ecosystems support 25% of all marine species and provide livelihoods for over 1 billion people, making their decline a humanitarian and ecological emergency.

Subjective Questions for Practise

Q1. What are the major causes of rising sovereign debt in developing countries? How it impacts the ability to respond to climate change and achieve sustainable development goals.

Q2. Evaluate the effectiveness of existing wildlife protection laws in India and propose reforms necessary to strengthen conservation efforts.

Q3. Critically examine the limitations of India’s current poverty measurement methods. How might updated national poverty metrics influence policy planning and social welfare outcomes?

QUICK LINKS