Down To Earth (01-15 January 2026)

The following topics are covered in the Down To Earth (01-15 January, 2026)

Eco-Anxiety: Emotional Crisis of a Changing Planet

Context

- In 2024, UNEP released Navigating New Horizons: A Global Foresight Report on Planetary Health and Human Wellbeing highlighting the world’s youth are facing a growing emotional and psychological crisis known as eco-anxiety or climate grief.

What Is Eco-Anxiety?

- Eco-anxiety refers to chronic fear, stress, or grief related to environmental damage and climate change. It can show up as:

- Persistent worry about the future;

- Feelings of helplessness or guilt;

- Anger at institutions or older generations;

- Grief for ecosystems, animals, or lost futures;

- Importantly, eco-anxiety is not a mental disorder. It is a natural response to the environmental crisis, especially among younger generations who feel the future is uncertain.

Why Is Eco-Anxiety Increasing?

- Constant exposure to alarming news via social media and 24/7 headlines;

- Lack of control over large-scale political and economic decisions;

- Moral pressure to live ‘perfectly sustainable’ lives;

- Unclear futures, especially around jobs, homes, and family planning;

- When threats feel global, invisible, and slow-moving, the brain struggles to process them, leading to chronic stress rather than short bursts of fear.

Evidence of a Generation’s Distress

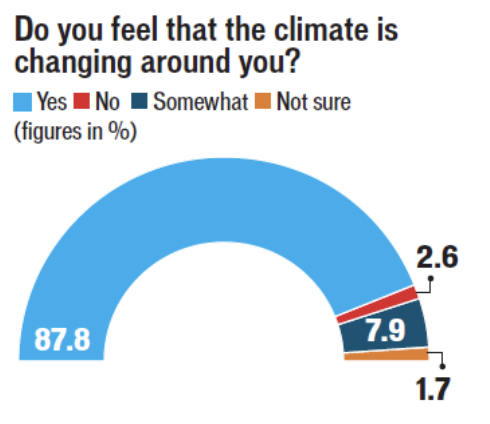

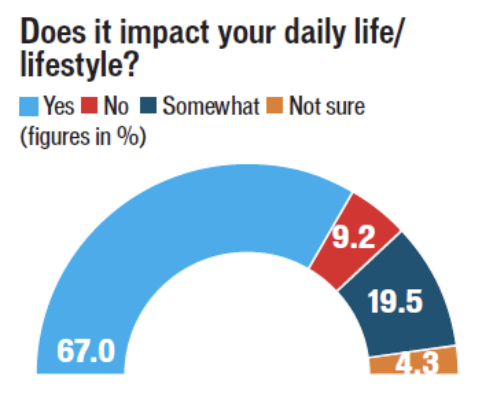

- A survey among over 300 people aged 16–25 years reveals how deeply eco-anxiety has taken root.

- 88% said they feel the climate is changing around them.

- 67% reported that these changes already affect their daily lives and habits.

- This generation, born into an era of climatic instability, may have never experienced what earlier generations called a ‘normal’ climate.

Living Through a Changed Climate

- Erich Fischer of ETH Zurich likened the climate’s behavior to ‘an athlete on steroids’.

- Data from Climate Central further show that anyone born after February 1986 has never experienced a month with normal global temperatures, every single month has been warmer than average.

What Young People Notice

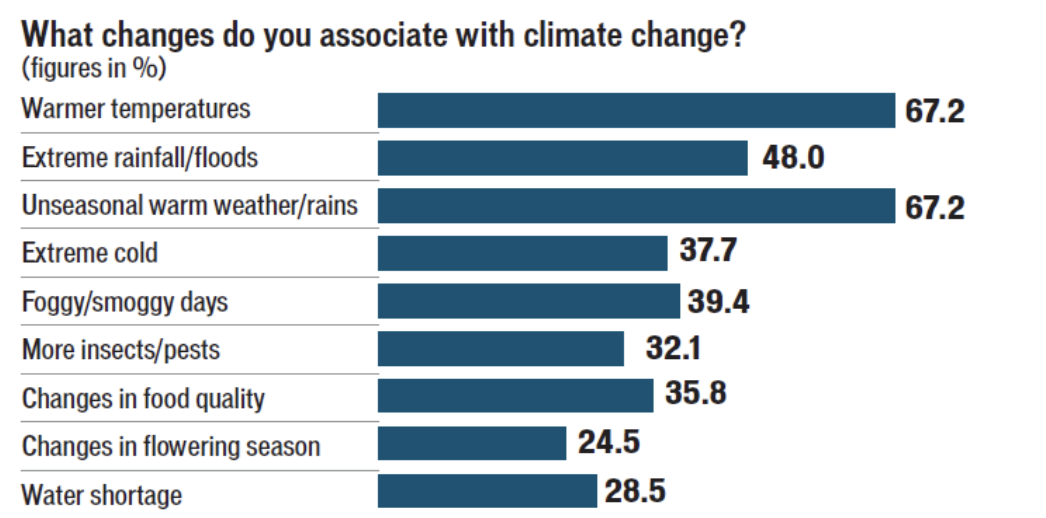

- Survey identified nine common manifestations of climate change as observed by youth:

- Warmer temperatures and unseasonal heat/rainfall recognized by more than two-thirds.

- Smog and fog were cited by 40%.

- Changes in food quality noted by 36%.

- Extreme cold mentioned by 38%.

- Rising insects and pests experienced by 32%.

- These symptoms reflect how climate change permeates everyday experiences from weather patterns to food and health.

Inequality in Impact

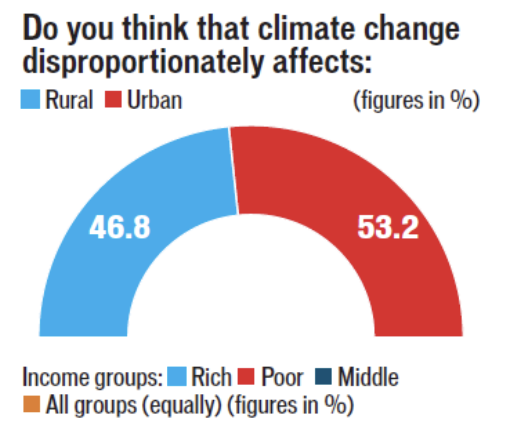

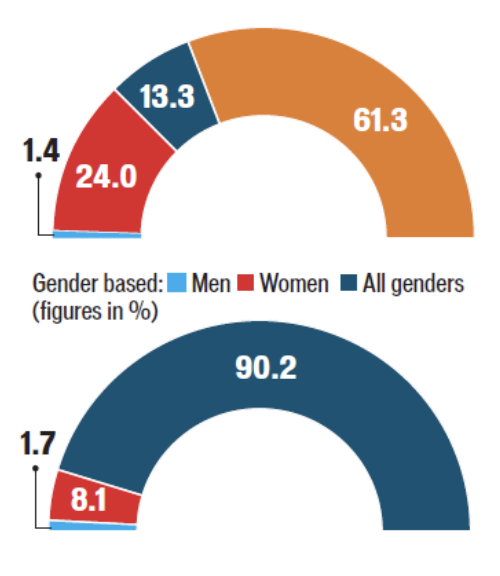

- While 61% of respondents believed that climate change affects all social classes equally, others disagreed asserting that the poor bear the brunt of environmental degradation.

- On gender differences, nearly 90% said the impacts are felt equally by men and women, suggesting a shared sense of vulnerability.

Emotional Landscape

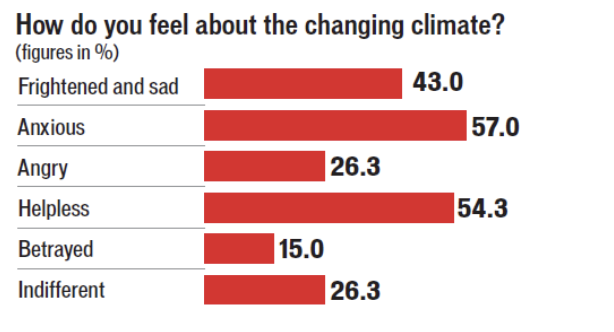

- The emotional cost is profound. When asked about their feelings toward climate change:

- 57% felt anxious;

- 54% felt helpless;

- 43% felt frightened or sad;

- Many also reported feeling angry or betrayed;

- These findings underline that eco-anxiety is not a fringe emotion, it is a widespread psychological response to a global threat.

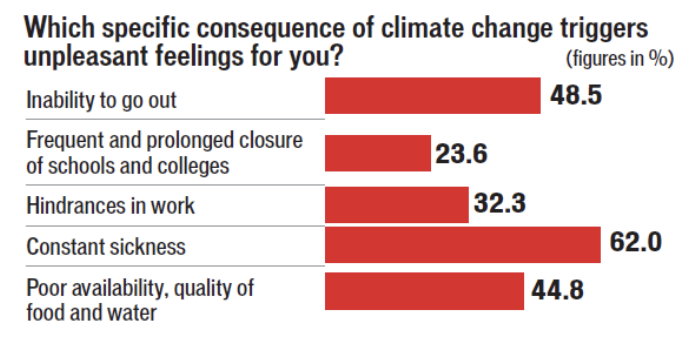

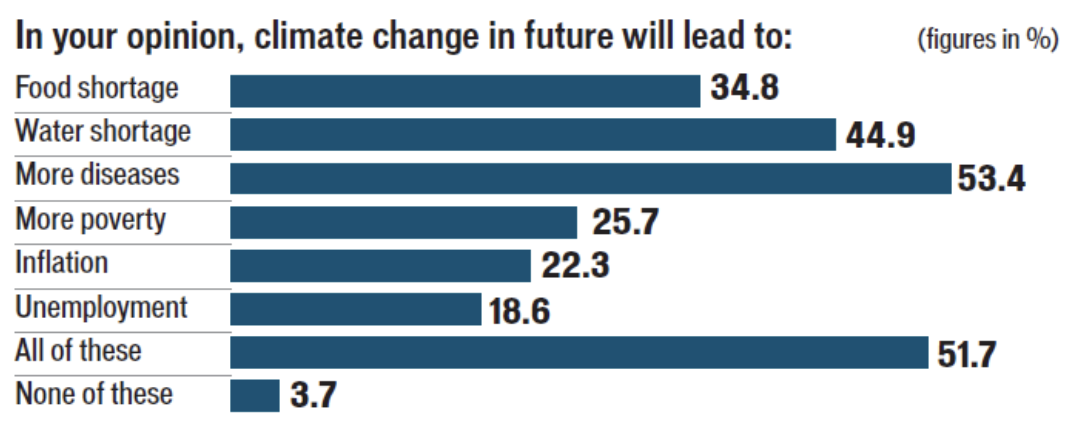

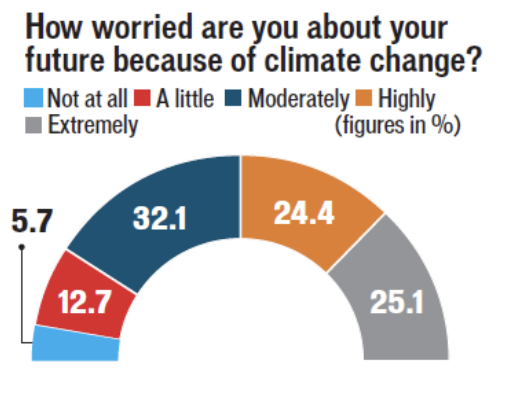

Fears for the Future

- 53% expect climate change to increase diseases.

- 45% foresee water shortages.

- One-third anticipate food crises.

- About 94% expressed worry about their future, while half described government action as ‘disappointing’.

Conclusion

- Eco-anxiety is not merely a personal issue; it is a societal signal. The distress felt by today’s youth mirrors the urgency of our planetary crisis.

- As UNEP’s 2024 report emphasizes, addressing this emotional catastrophe requires not only stronger environmental policies but also mental health support for a generation inheriting a rapidly changing world.

Waste, Infrastructure, and Eco-Anxiety on the Edge of an Expanding City

Context

- Urban India faces a complex intersection of waste generation, infrastructural strain, and climate-linked psychological stress.

- Recent studies reveal that unregulated urban expansion and poor environmental governance have intensified eco-anxiety, particularly among peri-urban communities and youth.

About

- India’s urban population reached 510 million in 2024, projected to exceed 650 million by 2036 (Census of India, 2024).

- It has blurred the boundaries between rural and urban zones, creating ‘urban edges’ that lack the governance, infrastructure, and ecological planning found in city cores.

- Recent research identifies these peripheral zones as hotspots of climate-induced psychological vulnerability, driven by unmanaged waste, pollution, and infrastructural neglect.

Urban Expansion and Infrastructural Inequality

- Growth of Peri-Urban Zones: Peri-urban areas such as Gurugram’s Sohna belt, Bengaluru’s Whitefield periphery, and Hyderabad’s Gachibowli fringe have seen exponential growth.

- However, 47% of new housing in these regions lacks basic waste disposal infrastructure.

- It results in mixed waste dumping, open burning, and contamination of water sources.

- These practices cause rising public health anxiety and stress symptoms consistent with eco-anxiety frameworks.

- Infrastructural Deficit: A 2025 NITI Aayog survey found that urban peripheries receive less than one-third of the municipal waste management budget per capita compared to central urban wards.

- In cities like Delhi, the Ghazipur landfill (65 meters high in 2025) symbolizes infrastructural collapse. Fire incidents at landfills, now occurring every 10–14 days, expose residents to methane and PM2.5 levels exceeding 400 µg/m³ during peak summer months.

Waste, Ecology, and Psychological Strain

- New Waste Economy: India now produces 74 million tonnes of solid waste annually (CPCB, 2025), up from 62 million in 2022.

- Only 28% is scientifically processed. The remainder accumulates in peripheral dumping sites like Bhandewadi (Nagpur), Okhla (Delhi), and Perungudi (Chennai).

- Residents living within 3 km of such dumps show two times higher risk of chronic anxiety and respiratory distress, a correlation linked to perceived environmental hopelessness.

- Waste Workers and Environmental Precarity: Informal waste pickers face compounding stressors: toxic exposure, stigma, and exclusion from formal municipal systems.

- These ‘eco-precarious livelihoods’ reflect a psychological toll rooted in systemic neglect rather than direct climate events, a form of ‘slow eco-anxiety’.

Eco-Anxiety in India

- Prevalence and Patterns: About 42% of Indian youth aged 16–24 experience moderate to severe eco-anxiety.

- Rates are higher among young women (54%) and residents of flood-prone urban slums (62%).

- The ‘environmental helplessness’ as a major psychological pattern among urban youth witnessing infrastructural collapse and pollution.

- Psychological Edge of the Expanding City: Climate anxiety in South Asian cities often centers around ‘infrastructural betrayal’, a feeling that governance systems have failed to protect citizens from ecological harm.

- Peripheral populations in cities like Delhi NCR, Chennai, and Pune show symptoms of chronic worry, fatigue, and disengagement from civic participation.

Policy, Infrastructure, and Emotional Resilience

- Integrating Peripheries into Waste Governance: Urban governance reforms recommend ward-level waste management autonomy, prioritizing decentralized composting and inclusion of informal workers.

- Sustainability frameworks must integrate mental health and ecological literacy, recognizing eco-anxiety as a legitimate public health issue.

- Circular Economy and SDG Alignment: New waste management strategies align with UN SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities) and SDG 13 (Climate Action). Cities like Indore and Surat have piloted Zero Waste Zones, cutting landfill dependency by 35% since 2023.

- However, urban fringes lag behind, requiring both infrastructural upgrades and psychosocial resilience training to address eco-anxiety.

Climate Change & Impact on Sports

Context

- Climate change is no longer a distant environmental issue, it is a present-day reality reshaping many aspects of human life, including sports.

- From grassroots community games to elite international competitions, rising temperatures, extreme weather events, and environmental degradation are increasingly influencing how, when, and where sports are played.

Rising Temperatures and Athlete Health

- One of the most immediate effects of climate change on sports is increasing heat.

- Heat stress and dehydration raise the risk of heat exhaustion and heatstroke.

- Endurance sports such as marathons, cycling, tennis, and football are particularly vulnerable.

- Athletes may experience reduced performance, slower recovery, and higher injury risk.

Extreme Weather Disrupting Competitions

- Climate change is increasing the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, including storms, floods, droughts, and wildfires.

- Common disruptions include:

- Flooded stadiums and pitches causing match cancellations;

- Storm damage to sports infrastructure;

- Poor air quality from wildfire smoke affecting outdoor events

- These disruptions create financial losses, scheduling chaos, and safety concerns for athletes and spectators alike.

Changing Playing Conditions and Performance

- Climate change alters the environment in which sports are played, affecting performance in subtle but important ways:

- Hotter air reduces endurance capacity

- Wind pattern changes influence sports like golf, sailing, and athletics

- Water temperature changes affect swimming, rowing, and open-water events

- Athletes now train for climate adaptability, not just physical skill.

Economic and Social Impacts

- Higher insurance costs for events and venues;

- Increased maintenance and repair expenses;

- Loss of revenue from canceled or relocated events;

- At the community level, climate change can reduce access to sport, particularly in vulnerable regions where facilities are damaged or unsafe.

Sports as Part of the Climate Solution

- While sports are affected by climate change, they also play a powerful role in climate action.

- Positive steps include:

- Building energy-efficient stadiums

- Reducing travel emissions

- Eliminating single-use plastics

- Promoting public awareness through athlete advocacy

- Because sports have massive global audiences, they are uniquely positioned to influence public behavior and attitudes toward sustainability.

Future of Sports in a Warming World

- Adapting to climate change is no longer optional for sports organizations. The future will likely involve:

- Climate-resilient infrastructure;

- Flexible scheduling models;

- New rules and safety standards;

- Stronger collaboration between sports bodies, scientists, and policymakers;

- The challenge is significant, but so is the opportunity—for sports to lead by example.

Oraon Adivasi Tribe of Jharkhand & Destruction of Nature

Context

- The Jharkhand plateau has long been known as the land of forests. For centuries, its dense sal forests, rivers, and hills have been home to many Adivasi (indigenous) communities.

- Among them, the Oraon tribe (aka Kurukh) stand out for their deep spiritual, cultural, and economic relationship with nature.

About Oraon Tribe

- The Oraons are traditionally settled cultivators and forest dwellers. Their worldview sees humans as part of nature, not masters over it.

- Forests are not merely resources; they are sacred living spaces.

- Key aspects of Oraon life connected to nature include:

- Agriculture: Rain-fed farming using indigenous seeds and traditional knowledge.

- Forests: Source of food, fuel, medicine, and livelihood.

- Water bodies: Rivers and ponds are central to daily life and rituals.

- Sacred groves (Sarna): Worship sites protected by strict customary laws.

- Their main festival, Sarhul, celebrates the marriage of the Earth and the Sun, symbolizing renewal of forests and life.

- Cutting trees or polluting water is traditionally considered a moral and spiritual offense.

Traditional Ecological Knowledge

- The Oraons possess generations of ecological wisdom:

- Use of herbal medicines derived from forest plants;

- Rotational farming to prevent soil exhaustion;

- Protection of biodiversity through sacred forest patches;

- This sustainable lifestyle allowed humans, animals, and forests to coexist harmoniously for centuries.

Destruction of Nature in Jharkhand

- In recent decades, Jharkhand has become a hub for mining and industrial projects due to its rich reserves of coal, iron ore, and bauxite. While these activities contribute to national economic growth, they have devastated local ecosystems.

- Major causes of environmental destruction:

- Mining and quarrying: Large-scale deforestation and land degradation;

- Industrial pollution: Contamination of rivers and groundwater;

- Commercial logging: Loss of sal forests and wildlife habitats;

- Dams and infrastructure projects: Displacement of villages;

- These changes have directly affected Oraon livelihoods, food security, and health.

Impact on the Oraon Community

- Loss of Forests: Forests that once provided fruits, firewood, medicines, and grazing land are disappearing.

- With them vanish traditional knowledge systems and cultural practices.

- Displacement and Migration: Many Oraon families are forced to leave ancestral lands due to mining projects.

- Displacement often leads to poverty, loss of identity, and migration to cities as unskilled laborers.

- Cultural Erosion: When sacred groves are destroyed, rituals like Sarhul lose their meaning. The younger generation, disconnected from land and forests, risks losing language, songs, and traditions.

- Health and Nutrition Crisis: Polluted water, reduced forest foods, and exposure to industrial waste have increased malnutrition and disease among Oraon communities.

Resistance and Environmental Movements

- Despite these challenges, the Oraons have not remained silent. They have been at the forefront of forest and land rights movements in Jharkhand, often invoking traditional laws and constitutional protections like the Forest Rights Act 2006.

- Village councils, women’s groups, and youth organizations continue to fight for:

- Protection of forests and sacred groves;

- Community control over natural resources;

- Sustainable development that respects indigenous rights;

Shift to Sustainable Materials Is Inevitable: Banofi Leather Leads the Change with Banana Fibre-Based Innovation

Context

- Banofi Leather (Banana fibre-based products) uses banana waste to produce vegan leather and has partnered with major fashion brands.

Rise of Sustainable Alternatives in Fashion

- The search for sustainable materials has become imperative with over 92 billion tonnes of textile waste generated annually and leather tanning identified as one of the most polluting industries.

- Among the most promising innovations is Banofi Leather, a vegan leather made from banana stem waste, a byproduct of the world’s fourth-largest agricultural crop.

- It offers a cruelty-free, low-carbon, and biodegradable alternative to animal leather.

Environmental Urgency for Change

- Traditional leather production contributes to 13% of the fashion sector’s total carbon emissions.

- Tanning processes release toxic chromium compounds into waterways.

- As consumers increasingly demand ethical and eco-friendly products, the global vegan leather market, valued at USD 73.38 billion in 2023, is projected to reach USD 92.36 billion by 2028.

- Plant-based leathers, including those derived from pineapple (Piñatex), cactus (Desserto), and banana (Banofi), are gaining traction among both luxury and fast-fashion brands.

What Is Banofi Leather?

- Banofi Leather, developed in India, upcycles banana stem waste, typically discarded after fruit harvesting into durable, flexible sheets that mimic the texture and resilience of animal hide.

- Production Process:

- Extraction of banana fibre from discarded stems.

- Processing using eco-friendly binders and natural resins.

- Finishing into fabric sheets with minimal water and energy use.

- The production of Banofi leather reduces water consumption by 85% and CO₂ emissions by up to 90% compared to traditional leather.

Industry Adoption and Global Collaborations

- Banofi Leather has partnered with major fashion labels to integrate banana-based vegan leather into accessories and apparel.

- Recent reports highlight collaborations with luxury footwear, sustainable handbags, and apparel designers in Europe and Asia.

- In 2024, Banofi was featured in the Sustainability Directory as one of the top five startups revolutionizing eco-materials in fashion.

- The company’s circular model supports local banana farmers, enhancing rural livelihoods while preventing millions of tonnes of agricultural waste.

Consumer Behaviour and the Gen Z Effect

- A study on urban Indian consumers found that 67% of Gen Z buyers prefer brands using bio-based materials, citing ethical sourcing and environmental preservation as key motivators.

- Banofi’s narrative, combining sustainability, innovation, and social impact aligns perfectly with this generational demand.

Economic and Social Implications

- Each tonne of banana stem waste converted into Banofi leather prevents 2.5 tonnes of CO₂ emissions and provides additional income for farmers.

- It aligns with India’s national sustainability goals and the UN SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production.

Future Outlook: Toward a Circular Fashion Economy

- As material science advances, innovations like Banofi leather could replace up to 25% of conventional leather by 2030.

- Continuous R&D, combined with brand collaborations and government incentives, could make banana-based leather mainstream within the next decade.

Pollution: Turning Ordinary Living into an Expensive Exercise in Survival

Context

- Clean air and water have become premium commodities, once a free and basic human right.

About

- According to the World Bank (2024), environmental degradation now costs low- and middle-income countries up to 8% of GDP annually due to healthcare costs, productivity loss, and premature deaths.

- Pollution, whether in the air we breathe, the food we eat, or the water we drink has silently inflated the cost of living, transforming daily existence into a survival struggle.

Air Pollution and the Cost of Health

- Recent data reveals that chronic exposure to PM2.5 pollution increases healthcare expenditures by up to 20% in urban households.

- Similarly, a study found that respiratory illnesses among schoolchildren were three times higher in polluted zones, leading to elevated family medical spending and absenteeism costs.

- Air purifiers, face masks, and air-quality apps have now become essentials, adding to daily household expenses.

- The global air purifier market grew by 12.4% in 2025 (OECD report).

- Cities like Delhi, Beijing, and Lagos recorded air quality index (AQI) values over 300 for more than 120 days in 2024, making filtered air a privilege, not a guarantee.

Water Scarcity and Toxicity

- A study reported that over 2 billion people lack access to clean water, forcing many to rely on bottled alternatives.

- Water purification costs in urban areas of Nepal, India, and Sub-Saharan Africa have risen by 35–60% due to industrial pollution.

- WHO (2024) estimates that polluted water contributes to 1.4 million deaths annually.

- In Nigeria, rising fossil fuel use and wastewater contamination led to a 40% increase in household utility expenses.

- As clean rivers turn toxic, families spend more on bottled water, filtration systems, and health treatments for waterborne diseases, costs that disproportionately affect the poor.

Economic Erosion: Pollution and Housing Costs

- Environmental pollution doesn’t just threaten health—it reshapes real estate markets.

- Pollution in Chinese cities reduces housing rents by 15–30% in affected areas, while pushing cleaner suburban zones into higher price brackets.

- Ironically, those who can least afford it end up living in the most polluted neighborhoods, a vicious cycle of environmental and economic inequality.

Agricultural Fallout

- A study demonstrated that soil contamination from pesticides and heavy metals reduces crop yields by up to 18%, inflating food prices.

- Additionally, microplastic pollution is now present in over 90% of global table salt (UNEP, 2024), increasing long-term health risks and dietary costs through medical dependence.

- Organic produce has become a necessity for safe consumption, yet remains financially inaccessible for many.

Pollution and Psychological Costs

- A study found that exposure to urban air pollution correlates with higher levels of anxiety and depression.

- It has led to rising mental health treatment costs and increased demand for green spaces and eco-tourism as psychological refuges.

- In polluted cities, tranquility itself has become commodified—manifesting in the booming wellness and eco-retreat industries.

New Class Divide

- Pollution has created a new socioeconomic hierarchy: those who can afford clean air, water, and organic food versus those who cannot.

- Pollution negatively correlates with the Quality of Life Index, especially among low-income groups.

- For millions, surviving pollution means paying for health insurance, filtration devices, energy-efficient homes, and green-certified transport, all of which widen economic gaps globally.

Pathways Forward

- Governments need to integrate pollution reduction with economic policy, to reverse this costly trajectory.

- Green finance initiatives can fund sustainable urban infrastructure.

- Low-carbon transport systems like Kampala’s electric BRT can reduce dependency on fossil fuels.

- Eco-innovation in agriculture and urban planning must be subsidized to make sustainable living affordable.

Uninhabitable Heat, Drought, and Extreme Weather

Context

- It seems unfair to bring an innocent life into a world sliding towards uninhabitable heat, drought and extreme weather

Ethical Dilemma of Birth in a Warming World

- As climate change accelerates, with 2025 marking one of the hottest years on record, a growing number of young adults are rethinking the morality and practicality of having children.

- Extreme heat, droughts, and climate disasters now threaten the very habitability of large regions of the planet.

- It has given rise to what sociologists call ‘reproductive climate anxiety’, where people question whether it is fair or even ethical, to bring new life into a collapsing biosphere.

A Planet Nearing Critical Heat Thresholds

- According to the One Earth, 2025 report, global surface temperatures are now averaging 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, with projections suggesting an overshoot beyond 2°C by 2040 if emissions remain unchecked.

- The Asian Development Bank’s 2025 Heat Study found that extreme heat exposure has tripled since 1980, with regions in South Asia and the Middle East already facing ‘lethal wet-bulb temperatures’, conditions under which human survival is impossible beyond several hours.

- One-third of humanity could experience 45°C heat regularly by 2070.

- Drought duration has increased by 29% since 2000, devastating crops and groundwater.

- The World Bank’s ‘Water in a Heated World’ (2024) report warns that freshwater availability will fall by half in key basins like the Indus and Nile before 2050.

- These trends suggest not just discomfort, but uninhabitability for many regions within a single generation.

Psychological and Ethical Dimensions

- 70% of young people (ages 16–25) report feeling ‘very worried’ about climate change, and 39% say they are hesitant to have children.

- Psychologists now classify this concern as eco-reproductive anxiety, a blend of fear, grief, and guilt regarding future generations.

- Women in climate-affected regions express heightened trauma, as drought and displacement disrupt reproductive health and autonomy.

- The fairness question thus becomes not merely philosophical, it is deeply psychological, affecting family planning decisions globally.

Harsh Realities

- India’s heat index reached a record 60°C in May 2024, killing over 2,000 agricultural workers.

- Horn of Africa droughts (2020–2025) displaced 5 million people, creating new ‘climate orphans’ (UNHCR, 2025).

- Australia’s ‘uninhabitable zones’ are expanding due to lethal heat and bushfires.

- Pacific islands are facing total submersion, forcing intergenerational relocation.

Farms, Food Systems, and Food Habits

Context

- Modern food systems, driven by industrial agriculture, global supply chains, and hyper-consumerism, have widened the gap between people and the land that sustains them.

- According to the FAO (2025), global food production now contributes to over one-third of greenhouse gas emissions, while 30% of all food produced is wasted. It comes at a grave ecological and cultural cost.

Evolution of Modern Food Systems

- From Subsistence to Industrial Agriculture: Traditional farming practices were local, diverse, and regenerative.

- However, post-1950s industrialization shifted focus toward monocultures, mechanization, and chemical fertilizers.

- The EU’s food system has become one of the least sustainable sectors, with nutrient depletion and soil erosion accelerating despite policy efforts like the Farm to Fork Strategy.

- Global Supply Chains and Hidden Costs: The global food web today moves goods across thousands of miles before they reach our plates.

- The consumers often lack awareness of these hidden environmental and ethical costs, perpetuating unsustainable demand cycles.

Environmental Consequences of Detachment

- Soil and Biodiversity Loss: The UNCCD (2024) warns that over 24 billion tons of fertile soil are lost annually due to intensive farming.

- Monoculture cropping has driven the extinction of local crop varieties, reducing biodiversity by an estimated 75% since 1900.

- Water Scarcity and Pollution: Agriculture consumes 70% of global freshwater, and chemical runoff contributes to ‘dead zones’ in major aquatic systems such as the Gulf of Mexico.

- The World Resources Institute (2024) found that one-third of rivers in agricultural regions now contain unsafe nitrate levels.

- Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Livestock farming remains a major emitter, responsible for 14.5% of all human-induced GHGs (FAO, 2025).

- The global shift to meat-heavy diets has intensified methane emissions, making diet reform a crucial component of climate action.

Human and Cultural Impact

- Loss of Food Traditions: Urbanization and globalization have eroded regional cuisines and local food knowledge.

- The ‘fast-food culture’ not only affects nutrition but also severs intergenerational connections to farming wisdom and traditional preparation methods.

- Health Consequences: Industrialized diets high in processed foods have triggered a global nutrition crisis where obesity coexists with malnutrition.

- The Lancet Global Health Report (2024) revealed that over 2.3 billion adults are overweight or obese, while 800 million remain undernourished reflecting a deep imbalance in global food equity.

Emerging Solutions: Reconnecting with the Land

- Regenerative Agriculture Movement: Regenerative practices such as crop rotation, composting, and agroforestry are regaining ground.

- These methods restore soil health and sequester carbon.

- A 2025 Nature Food analysis showed that regenerative farms can reduce emissions by 30% and increase biodiversity by 50% compared to industrial monocultures.

- Urban and Local Food Systems: Urban agriculture and local food networks, from rooftop gardens to farmers’ markets, help reforge direct relationships between consumers and producers.

- The FAO’s 2024 ‘City Food Initiative’ estimates that urban farms could supply up to 20% of city vegetable needs, promoting food security and awareness.

- Conscious Consumption: The rise of ‘farm-to-fork’ movements, zero-waste lifestyles, and plant-based diets indicate a cultural reawakening.

- Apps like Too Good To Go and Imperfect Foods are examples of technology reconnecting ethics and appetite.

Cascading Effects of Species Disappears From a Land

Context

- When a species disappears from a land, the loss extends far beyond the species itself.

About

- The disappearance of a species from an ecosystem represents more than the loss of a single organism as it initiates a cascade of ecological, economic, and cultural repercussions.

- Recent research underscores that biodiversity decline disrupts food webs, alters nutrient cycles, and weakens ecosystem resilience against climate change.

- According to the IPBES Global Biodiversity Report (2024), an estimated one million species are at risk of extinction, and many local extinctions are already reshaping ecosystems worldwide.

Ecological Web: Interconnectedness of Life

- Trophic Cascades and Food Web Instability: When a species vanishes, the delicate balance of the food web collapses.

- A study found that local extinction of pollinators in Himalayan regions led to a 32% decline in alpine plant regeneration, illustrating how the loss of one group triggers widespread ecological decline.

- Predators, herbivores, and decomposers all rely on complex interdependencies, the disappearance of even a single keystone species can send shockwaves through the entire system.

- Keystone Effect: Species such as wolves, bees, or mangroves act as ‘keystones’ and their removal destabilizes entire ecosystems.

Cultural and Economic Consequences

- Livelihoods at Risk: Species loss jeopardizes human economies. The global decline of beneficial insects has cost agriculture over $577 billion annually in lost pollination services.

- Communities dependent on fisheries, forest products, or ecotourism face social and economic collapse following species disappearance.

- Cultural Erosion: Indigenous communities suffer cultural loss when species that form the core of traditional knowledge and spiritual identity vanish.

- The disappearance of medicinal plant species from Amazonian regions has erased centuries of ethnobotanical wisdom.

Hidden Cascades: Soil, Climate, and Water Systems

- Soil Degradation: Species extinctions disrupt microbial and fungal symbioses, degrading soil fertility.

- Studies published in Nature Ecology & Evolution (2024) highlight that soil biodiversity loss correlates directly with declining carbon sequestration capacity, reducing ecosystem climate resilience.

- Hydrological Impacts: Wetland species extinctions, such as the decline of amphibians and aquatic plants, disturb water purification systems.

- The World Water Development Report (2024) found that watersheds losing native aquatic species show a 40% decrease in natural filtration efficiency.

Recent Global Trends and Data

- UNEP (2024) reported that 68% of vertebrate populations have declined since 1970.

- Insects are declining by 2% annually, risking collapse of pollination networks.

- Forest biodiversity loss has reduced global carbon storage by 7 billion tons annually.

- Coral reef extinction is projected to affect 500 million people relying on marine biodiversity.

- Local bird extinctions in European grasslands have reduced natural pest control by 26%.

Pathways to Recovery

- Restoring Ecological Networks: Rewilding initiatives like reintroducing lost species like bison or wolves have shown promise.

- The European Rewilding Network (2025) reported measurable recovery in soil and water quality following species reintroduction

- Technological and Policy Innovations: DNA barcoding, habitat restoration drones, and AI-based monitoring are emerging tools.

- The Global Biodiversity Framework calls for protecting 30% of Earth’s land and oceans by 2030, integrating community-based conservation and technology.

Subjective Questions for Practise

Q1. In what ways has eco-anxiety influenced your perception of the future, and how do you believe individuals and communities can transform this emotional response into meaningful environmental action?

Q2. How is climate change reshaping the way sports are played, organized, and experienced, and what responsibilities do athletes, organizations, and fans have in addressing these challenges?

Q3. How do modern food systems influence our personal food habits, and what role can sustainable farming play in reshaping our relationship with food?

QUICK LINKS