Down To Earth (01-15 December, 2025)

The following topics are covered in the Down To Earth (01-15 December, 2025)

Promise and Paradox of Rooftop Solar Power

Context

- Despite the technological and environmental promise, the transition to rooftop solar has not scaled up as expected in India, because of the deep structural challenge of integrating solar energy into existing power systems.

Solar Power in India

- India has an ambitious goal of achieving 500 GW of renewable energy capacity by 2030, with 280 GW expected from solar.

- Within this, rooftop solar (RTS) — decentralized power generated on residential and commercial buildings — emerges as both a promise and a paradox.

- It faces systemic hurdles that challenge its scalability, while it promises democratized energy access and reduced carbon footprint.

Promise: Democratizing Energy Generation

- Decentralized Energy Access: According to the MNRE, rooftop solar installations empower consumers to become ‘prosumers’—both producers and consumers of energy.

- It reduces transmission losses and strengthens grid resilience.

- Environmental and Economic Benefits: A 1 kW rooftop solar system can offset around 1.2 tonnes of CO₂ per year, contributing substantially to India’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs).

- Furthermore, RTS offers long-term savings—reducing household electricity bills by 30–40%.

- Job Creation and Local Economies: MNRE reports indicate that every megawatt of rooftop solar installed creates around 24 direct jobs—far higher than centralized coal or hydro projects.

- It includes opportunities for local technicians, electricians, and maintenance services.

Paradox: Potential vs. Reality

- Lagging Behind Targets: Despite a target of 40 GW by 2022, as per Central Electricity Authority, only 11 GW has been achieved.

- The reasons are multifold—policy inconsistency, poor implementation, and limited consumer awareness.

- Financial Barriers: Even with government subsidies under schemes like the Grid Connected Rooftop Solar Programme (Phase II), upfront installation costs remain prohibitive for middle-class households.

- Financial institutions often perceive RTS loans as high-risk, limiting credit flow.

- Distribution Companies’ (DISCOMs) Reluctance: DISCOMs view rooftop solar as a threat to revenue.

- Reduced electricity consumption from grid-connected customers affects their financial stability, leading to delays in net-metering approvals and cumbersome bureaucratic procedures.

- Technological and Maintenance Challenges: Issues like poor panel quality, inefficient inverters, and lack of skilled maintenance services affect long-term system reliability—dampening public confidence in rooftop solar projects.

- Integration Challenge: As per the CEA, India’s power demand during evening hours (6 pm–11 pm) accounts for nearly 30% of daily consumption, precisely when solar power is unavailable.

- Without efficient storage or pricing mechanisms, this imbalance puts pressure on distribution companies (discoms).

Kerala’s Case Study

- The Kerala State Electricity Board (KSEB) has installed 1.5 GW of rooftop solar, covering 2% of households.

- It exposed the financial vulnerability of utilities while celebrated as a success.

- The Kerala State Electricity Regulatory Commission (KSERC) introduced new rules requiring mandatory battery storage for systems above 10 kW, scaling up over time to include smaller setups.

- It aims to ease grid pressure by encouraging local storage and peak-hour supply. However, it raises installation costs, potentially discouraging middle-class adoption.

- According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), distributed solar systems could meet up to 45% of global electricity demand by 2050—if integrated with smart grids and affordable storage.

- Without these, excess daytime generation and inadequate nighttime supply could destabilize national grids.

Building the Solar Future

- India and other nations need to rethink how electricity systems are designed to make rooftop solar truly transformative. Some key steps include:

- Grid Modernization: Smart meters and dynamic pricing to reflect real-time demand.

- Battery Incentives: Subsidies or tax rebates to reduce upfront storage costs.

- Peer-to-Peer Trading: Allowing local power exchange between solar homes and businesses.

- Decentralized Mini-Grids: Especially in rural areas without reliable grid connectivity.

- Tariff Reforms: Encouraging power use during daylight and disincentivizing heavy nighttime consumption.

India’s Climate Catastrophe: PLOS Climate

Context

- A recent study published in PLOS Climate warns that India is on track for catastrophic climate events, with multiple systems — atmospheric, oceanic, and cryospheric — undergoing alarming transformations.

Key Findings

- India’s average temperature has risen by 0.9°C between 2015–2024, compared to the 1901–1930 baseline.

- The frequency and duration of heatwaves have increased significantly, with most regions now experiencing 5–10 more ‘Warm Days’ per decade.

- 2024 alone witnessed more than 200 heatwave days across India, with states like Rajasthan, Gujarat, and Uttar Pradesh recording temperatures above 47°C.

- Urban heat islands have further exacerbated local warming due to unplanned construction and dwindling green cover.

- Monsoon in Disarray: The southwest monsoon, the backbone of Indian agriculture, is becoming erratic.

- Extreme precipitation events have intensified in central India and coastal Gujarat, while mean rainfall has declined across the Indo-Gangetic plains and the Northeast.

- 2023 saw record-breaking rainfall anomalies, with floods in Himachal Pradesh and droughts in Bihar within the same season — a paradox that reflects the growing instability of the monsoon system.

- Climate models now project a 6–8% rise in all-India mean monsoon rainfall by 2050, driven by increased moisture in a warmer atmosphere.

- Warming Oceans: The tropical Indian Ocean, which plays a critical role in shaping India’s climate, is heating at 0.12°C per decade — faster than the global average.

- The PLOS Climate paper projects that marine heatwaves could last for nearly 200 days annually by 2050, compared to just 20 days in the recent past.

- These heatwaves have already led to coral bleaching in the Lakshadweep and Andaman Islands and are disrupting monsoon circulation patterns.

- Melting Himalayas: The Hindu Kush Himalaya is warming at 0.28°C per decade, nearly twice the global rate.

- The study projects a 30–50% reduction in glacier volume by 2100, even under moderate warming scenarios (1.5–2°C).

- It has grave implications for water security — rivers such as the Ganga, Brahmaputra, and Indus, which sustain over 700 million people, depend heavily on glacial melt.

- Human and Economic Toll: India lost over 3,000 lives to extreme heat in the last five years, and the World Bank estimates climate-related losses could cost India up to 2.8% of its GDP annually by 2050.

- Urban centers face heat stress and air pollution, while rural communities grapple with crop failures and groundwater depletion.

- India’s food security is at risk, with wheat and rice yields projected to decline by 10–15% under current warming trends.

Way Forward

- An integrated approach combining climate-resilient agriculture, early warning systems, urban green planning, and renewable energy expansion.

- India’s updated National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC) must prioritize local adaptation, not just mitigation.

- Community-led water management and afforestation efforts — as seen in parts of Maharashtra and Rajasthan — show promise, but scaling them nationally remains a challenge.

India’s Draft Seeds Bill, 2025

Context

- Recently, the Union government’s Draft Seeds Bill, 2025 seeks to ‘modernize and digitize’ the seed sector, while farmer groups and seed keepers see it as a threat to traditional practices and community rights.

Background: Policy Context

- The Bill revises the long-pending Seeds Bill, 2019, which itself was meant to replace the Seeds Act of 1966.

- The 2025 draft aligns with the Centre’s push toward digital governance and agri-standardization, complementing schemes like Digital Agriculture Mission and PM Kisan Samriddhi Yojana.

- However, it is argued that such policies prioritize market efficiency over seed sovereignty and agrobiodiversity.

Key Provisions of the Bill

- Mandatory Seed Registration: All seed varieties—domestic or imported—must be registered with the Centre, except farmers’ traditional varieties and seeds produced exclusively for export.

- Value for Cultivation and Use (VCU) Testing: Only varieties passing VCU tests, which assess performance, yield, and adaptability, can be approved for sale.

- The bill mandates minimum standards for germination, purity, and seed quality.

- Dealer Registration: Seed dealers, producers, and distributors must obtain a state-issued registration certificate before engaging in seed trade, import, or export.

- Digital Traceability: Every seed container must carry a QR code generated through the Centre’s Seed Traceability Portal, ensuring end-to-end tracking and verification.

Concerns from the Ground

- Threat to Community Seed Systems: Farmer organizations warn that the Bill categorizes community seed groups, including Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs) and women’s seed collectives, as commercial entities, bringing them under the same regulatory obligations as corporate seed firms.

- Bias Toward Hybrid Varieties: VCU trials often favour uniform, high-input hybrid varieties typically produced by large agribusinesses.

- It marginalizes indigenous, open-pollinated, and climate-resilient varieties, which may perform well in diverse local conditions but not under standardized testing.

- Digital Divide and Compliance Burden: Mandatory digital reporting through the Seed Traceability Portal poses challenges for smallholder farmers and rural seed keepers with limited internet access or digital literacy.

- Rural seed producers fear exclusion from the formal system due to ‘digital-heavy compliance norms’.

- Lack of Farmer Representation: The Bill does not clearly specify mechanisms for farmer participation in the registration or testing process.

- Farmer unions demand local-level consultation and the inclusion of traditional knowledge holders in decision-making.

- Environmental and Economic Implications: India’s informal seed sector—dominated by farmer-to-farmer exchanges—supplies nearly 60% of all seeds used.

- Overregulation could disrupt these informal networks, potentially increasing dependence on commercial seed companies and narrowing the genetic base of cultivated crops.

- Moreover, the shift to centralized digital systems raises questions about data privacy, seed patenting, and corporate control over agricultural information.

Public Consultation and the Way Forward

- The Bill is open for public comment until December 11, 2025. Civil society organizations urge the government to:

- Exempt smallholder and community seed exchanges from licensing.

- Create region-specific VCU criteria for diverse agro-climatic conditions.

- Ensure digital inclusion through local-language interfaces and offline mechanisms.

- Establish a National Farmers’ Advisory Council to oversee seed governance.

Global Rise and Risks of Ultra-Processed Foods

Context

- According to a three-part series in The Lancet published recently, the ultra-processed food (UPF) corporations have embedded themselves deeply into scientific research, policy-making, and public health narratives—often under the guise of ‘stakeholders’.

What Are Ultra-Processed Foods (UPFs)?

- UPFs are industrial formulations made from cheap food-derived ingredients, additives, and preservatives. These include chips, biscuits, carbonated drinks, and ready-to-eat meals, often engineered for hyper-palatability and long shelf life.

- UPFs are designed to replace traditional diets and maximize profit margins, unlike minimally processed foods

- Such products dominate global markets due to aggressive marketing, convenience, and affordability, especially in low- and middle-income countries.

Health Consequences

- Scientific consensus increasingly links UPF consumption to chronic non-communicable diseases (NCDs), including:

- Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes;

- Hypertension and Cardiovascular Diseases;

- Chronic kidney disease;

- Gastrointestinal and metabolic disorders;

- Regular consumption of UPFs contributes to gut microbiome imbalance, promoting inflammation and metabolic dysfunction.

- Moreover, the hidden sugar, salt, and fat content often exceeds WHO-recommended limits.

India’s Emerging Challenge

- In India, UPFs are gaining rapid market share, particularly among urban and adolescent populations.

- About 68% rise in packaged snack consumption between 2011 and 2021, correlating with an increase in childhood obesity and early-onset diabetes.

- Experts warn that UPF industries are replicating tobacco-style tactics—funding misleading studies, sponsoring sporting events, and rebranding products as ‘healthier alternatives’.

Policy and Global Health Implications

- Independent research funding free from corporate influence;

- Front-of-pack warning labels for UPFs;

- Stricter regulation of food marketing to children;

- Fiscal policies (taxes/subsidies) to promote fresh foods;

- Governments need to resist industry lobbying and prioritize public health over profit to prevent UPFs from overwhelming food systems worldwide.

Reclaiming the Ravines: Chambal’s Badlands

Context

- The ravines of the Chambal River—spanning Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, and Uttar Pradesh are reshaping both the landscape and its fragile ecosystems.

Overview: Chambal Ravines

- The Chambal Ravines are a unique geomorphological feature formed by severe gully erosion along the Chambal River basin (a tributary of the Yamuna).

- The process is largely anthropo-geomorphic—human activity has intensified natural erosive forces.

- The ravines are a natural consequence of the semi-arid region’s geomorphology formed by centuries of water and wind erosion.

- From soil erosion due to unscientific agricultural practices, deforestation, and natural weathering of the alluvial plains.

- Steep slopes and the semi-arid climate accelerate runoff erosion, cutting deep gullies into the terrain.

Ecological Significance

- The ravines host patches of dry deciduous forest, grassland, and scrub habitats supporting Indian gazelle (chinkara), Indian fox, and mugger crocodiles near the riverine tracts.

- The National Chambal Sanctuary (est. 1979) protects species like the gharial, Gangetic dolphin, Indian Skimmer and red-crowned roofed turtle.

Socio-Economic Impact

- The ravines render large tracts unfit for cultivation, causing economic distress and migration among local communities.

- Historically, the Chambal valley was associated with dacoit activity, fostered by the rugged terrain and poor governance.

Government Initiatives

- Ravine Reclamation Projects (since 1980s) – coordinated by the Central Soil and Water Conservation Research and Training Institute (CSWCRTI).

- NITI Aayog’s 2020 Initiative – plan to convert ravines into productive agroforestry lands through a public-private partnership model.

- Madhya Pradesh Ravine Reclamation Project – aims to reclaim 60,000 hectares using bioengineering, check dams, and agroforestry.

Recent Developments (2020–2024)

- ISRO and NRSC mapping initiatives have classified ravine severity for targeted land restoration.

- Pilot projects in Morena and Bhind districts demonstrate successful carbon sequestration via tree plantations.

Challenges

- Continued illegal sand mining and deforestation.

- Fragmented policy coordination between central and state agencies.

- Lack of community participation in restoration programs.

COP30 in Belém: COP of Truth & Implementation

Context

- The UN’s 30th climate summit, COP30 in Belém, Brazil, was billed as the ‘COP of truth and implementation’, as it exposed deep fractures within the global climate regime and highlighted the growing irrelevance of a system struggling to keep pace with the worsening crisis.

A Warming World on the Brink

- Ahead of the summit, the WMO reported that 2025 is likely to be the second or third warmest year on record, extending the streak of extreme global heat.

- The UN Environment Programme’s ‘Emissions Gap Report’ warned that the world is heading for 2.8°C of warming, with the 1.5°C threshold likely to be breached within the next decade.

- Overshooting this limit is likely to trigger irreversible climate feedback — melting ice sheets, collapsing ecosystems, and unmanageable heatwaves.

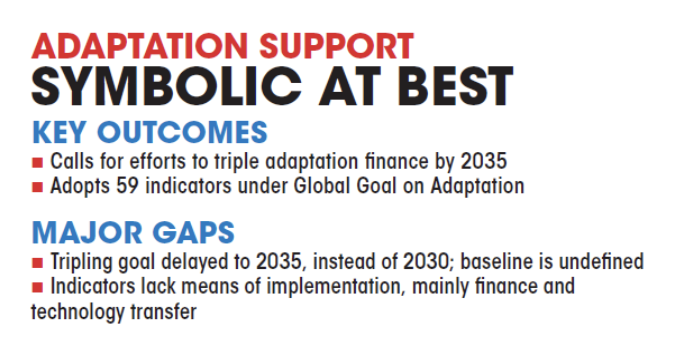

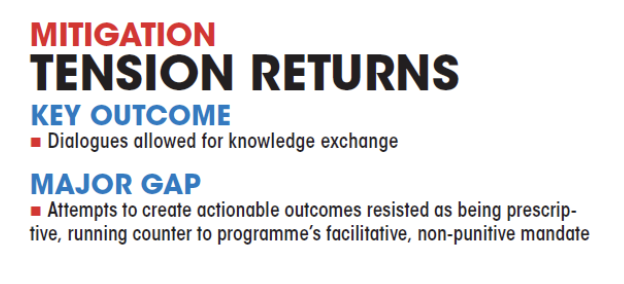

Belém Political Package: More Symbolism Than Substance

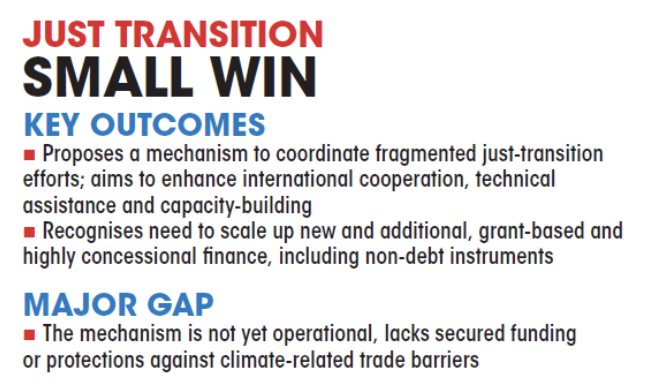

- The Brazilian presidency adopted the Belém Political Package, heralded as the core outcome of COP30. Its highlights included:

- A new mechanism for international cooperation on a just transition, aimed at balancing development and decarbonization.

- Vague commitments to triple adaptation finance by 2035.

- A new work programme under Article 9 of the Paris Agreement to track financial flows from developed to developing countries.

- But, crucially, no reference was made to phasing out fossil fuels—a glaring omission in a year when record wildfires and droughts underscored the urgency of transition.

- Brazil deferred the fossil fuel discussion to a later roadmap, mirroring the slow diplomacy described as ‘climate multilateralism caught in paralysis’.

Divided and Distrustful: North–South Rift Deepens

- The G77+China bloc — a coalition of 134 developing nations—emerged as a significant force, demanding accountability and finance.

- However, developed nations attempted to scapegoat large developing economies as ‘blockers’ of ambition, exposing what DTE called a ‘crisis of legitimacy in the COP process’.

- The developed world’s insistence on framing ambition without equity drew criticism.

- It is observed that ‘the Global North continues to posture as a climate leader while failing to meet its own pledges’, noting that many NDCs (nationally determined contributions) from developed countries remain insufficient or unimplemented.

- Meanwhile, countries like China and India—often targeted as obstructors—are in fact expanding renewable energy capacity at record pace.

- China leads globally in clean tech deployment, and India is set to exceed its 2030 solar targets by 2027.

Global Mutirão: A Symbolic ‘Collective Effort’

- Brazil’s presidency introduced the Global Mutirão Decision (‘mutirão’ meaning collective effort).

- It bundled unresolved developing-country demands outside the formal negotiation tracks. The four key issues addressed were:

- Climate finance from developed to developing nations.

- The 1.5°C implementation gap.

- Transparency under the Paris Agreement.

- Trade-related climate measures and their fairness.

Prime Priorities: Declarations & Mechanisms During COP30

- Integrated Forum on Climate Change and Trade: To create a permanent, politically supported space for countries to address increasingly contentious intersections between trade policies and climate action.

- Declaration on Information Integrity on Climate Change: To uphold integrity of public information, protect scientists and journalists and counter spread of false narratives undermining climate action.

- Launch of Ocean Taskforce: To build on Blue Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) Challenge, which encourages countries to set ocean protection targets when updating NDCs, and integrate oceans into a global mechanism accelerating adoption of marine solutions in national climate plans.

- Belém 4x Pledge on Sustainable Fuels: To provide political support and promote international cooperation to increase at least fourfold the use of sustainable fuels by 2035, from 2024 levels, through implementation of policies.

- Resilient Agriculture Investment for net-Zero land degradation accelerator: To restore degraded farmland and mobilise finance.

- It is designed to help governments map degraded land, identify viable restoration projects and build financing tools for private capital.

- Belém Health Action Plan: World’s first international climate adaptation framework dedicated entirely to health.

- It provides a roadmap for countries to confront escalating climate-related health threats, from heatwaves and vector-borne diseases to disruption of food and water systems.

- Belém Declaration on Hunger, Poverty, and Human-Centered Climate Action: To call for a pivotal shift in how the international community addresses the climate crisis, recognising that, while climate change affects everyone, its devastating impacts fall disproportionately on the world’s poorest communities.

- Declaration for a Global Transport Effort: To align the transport sector, the second-largest emitting sector, with the 1.5°C goal.

- The declaration calls for a global transport effort to achieve by 2035, a 25% drop in overall energy demand from transport, and shift one-third of transport energy to sustainable biofuels and renewable sources, with differentiated pathways.

- Tropical Forest Forever Facility: To provide longterm, self-financing support for tropical forest conservation.

- It was launched with US $5.5 billion in commitments, with a long-term goal of raising $125 billion.

- At least 20% of all payments will flow directly to Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities.

- Transport decarbonization in India, Mexico and Europe:

- India aims to deploy 15,000 zero-emission trucks, 1,500 electric vehicle charging infrastructure units, and 78 MW renewable energy supply capacity by 2030;

- Mexico aims to deploy over 17,000 zero-emission vehicles by 2030; and

- Europe aims to deliver a European transport decarbonisation action strategy.

- Plan to Accelerate Minerals for the Transition and Circularity: To overcome primary challenges to the clean energy transition: improving supply chain data quality, coordinating to expand electricity grids, embedding circularity and resilience into supply chains, and enabling developing economies to move up the clean power value chain through investment and skills partnerships.

- Farmers’ Initiative for Resilient and Sustainable Transformations: To reduce methane and nitrous oxide emissions from the agriculture sector, two potent greenhouse gases that together account for 40% of human-emitted methane and 75% of nitrous oxide.

- Belém Gender Action Plan: To ensure women and girls are placed at the centre of climate policies with new provisions on health, violence and protection for women environmental defenders.

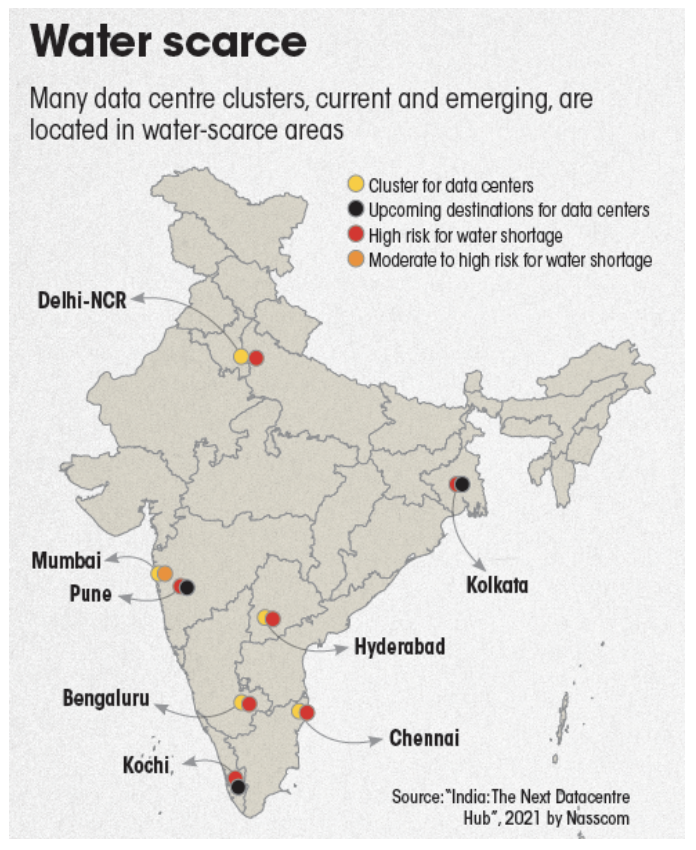

India’s Data Centre & Hidden Water Crisis

Context

- India is setting up large-scale data centres in water-scarce regions as it races to expand its digital capabilities, raising alarms about the long-term sustainability of India’s digital growth.

More About News

- India is rapidly positioning itself as a global hub for data centres—the backbone infrastructure powering the world’s digital operations.

- These facilities store and process vast amounts of data generated by online activities, artificial intelligence (AI) systems, and cloud services.

- However, behind this technological leap lies a pressing environmental challenge: the immense water requirement for cooling servers and maintaining system efficiency.

India’s Emerging Data Centre Hub

- The 1990s saw the birth of data centres, but the rise of cloud computing, internet penetration, and AI workloads has exponentially increased their demand.

- McKinsey & Company (2024) projects that by 2030, 70% of new data centre capacity will cater to AI-related operations.

- According to a Deloitte report (2025), India now hosts around 150 operational data centres across major Tier-1 cities, with a combined IT load capacity of 1,200–1,300 MW.

- The report predicts India will record the highest capacity addition in the Asia-Pacific region between 2024 and 2026, outpacing countries like Japan and Singapore.

- India’s advantages—lower operational costs, skilled workforce, and strategic location—make it a global favourite. But these benefits mask a growing environmental cost.

Data Centres and Their Thirst for Water

- A data centre houses high-performance servers, routers, and storage systems, all of which generate substantial heat during operation.

- Most facilities use water-based cooling systems, drawing from groundwater or surface water sources to prevent overheating.

- A 1 MW data centre with water-based cooling typically consumes about 26 million litres of water annually.

- Yotta’s facility, with a capacity of 30 MW, could potentially use 780 million litres per year—enough to meet the annual domestic water needs of around 15,830 urban residents.

- Although Yotta claims to use air-based cooling technology, limiting water use to 6 million litres per year, its total approved limit stands at 43 million litres annually.

Hidden Cost: Water Stress and Environmental Impact

- India ranks among the top 25 most water-stressed countries, as per the World Resources Institute’s Aqueduct Water Risk Atlas.

- Their concentration in already water-stressed areas could exacerbate regional water crises, with data centres being heavy water consumers.

- A 2025 Planet Tracker analysis found that 50 data centres in India are located in ‘extremely high’ water-stressed regions, second only to Indonesia in Asia.

- The water footprint of these facilities varies by climate, size, and technology, but collectively, they pose a substantial risk to groundwater sustainability.

Environmental Clearance and Oversight Gaps

- Data centre projects in Uttar Pradesh require environmental clearance from the State-level Environmental Impact Assessment Authority (SEIAA), based on recommendations from the State-level Expert Appraisal Committee (SEAC).

- Yotta received clearance in 2020, conditional upon obtaining groundwater extraction permission from the Central Ground Water Authority (CGWA).

- However, officials have not confirmed whether such permission was granted, and the company maintains that no borewells have been dug.

- Furthermore, Yotta has not published an Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) report, despite growing calls for corporate transparency in sustainability practices.

Local Impacts and the Road Ahead

- Investigations in Bengaluru and Gautam Buddha Nagar, two of India’s major IT hubs, reveal growing tensions between technological progress and local water security.

- Residents face the daily reality of declining groundwater levels and insufficient water access, while companies highlight innovation and economic growth.

- India’s digital expansion could deepen existing inequalities and environmental degradation, without stronger environmental regulation, transparency, and water-efficient technologies.

Data Centre Cooling Technologies

- Evaporative Cooling (Efficient but Water-Intensive): It uses water to remove heat from servers, offering high energy efficiency.

- However, it requires constant water replenishment, particularly in hot or arid regions, making it less sustainable where water scarcity is prevalent.

- In cities like Bengaluru or Noida, where freshwater resources are already strained, the dependence of evaporative systems on continuous water supply raises significant environmental concerns.

- Air-Cooled Chillers: They dissipate heat using large fans. These systems consume little to no water, making them attractive in water-stressed regions.

- However, they demand considerably more electricity than water-based systems, which can negate their environmental benefits if the power grid is heavily reliant on fossil fuels.

- Liquid Cooling Technologies: It involves submerging servers and chips in a special dielectric (nonconductive) fluid, which absorbs heat directly from components.

- The fluid then transfers heat to a heat exchanger, where it is cooled before recirculating.

- Immersion cooling delivers significant energy savings and uses far less water than either evaporative or air-based systems.

- Although it entails higher upfront costs, it offers long-term benefits in efficiency, reliability, and environmental sustainability.

Reviving Punjab’s Borewells For Flood Mitigation and Groundwater Replenishment

Context

- The state of Punjab in India needs to shift from short-term recovery to long-term flood management, as it faced the worst flood in four decades due to the southwest monsoon in 2025.

Punjab’s Borewells & Agricultural Role

- It has 1.4 million abandoned borewells that became central to Punjab’s agricultural landscape during the Green Revolution of the 1960s.

- The number of borewells multiplied rapidly—especially after 1997–98, when water tables stood around 12 metres, as farmers switched to groundwater irrigation.

- However, decades of over-extraction have since pushed groundwater levels down to depths of 150 metres or more, rendering many borewells defunct.

Turning a Threat into an Opportunity

- Research by the ICAR–Indian Institute of Soil and Water Conservation (IISWC) demonstrates that abandoned borewells can be revived into effective underground recharge systems with minor modifications.

- It begins with a hydrogeological assessment to verify the borewell’s depth, water quality, and structural condition.

- Once deemed safe, the borewell is cleaned, flushed, and refitted with slotted PVC pipes to facilitate filtration and infiltration.

- Recharge Pit Design: A recharge shaft is then constructed following the Indian Standard IS 15797:2008.

- The shaft’s filter media—a layered combination of coarse sand, gravel, and pebbles—ensures that only clean water percolates downward.

- A recharge pit surrounds the borewell, lined with brick, stone, or reinforced concrete. Rainwater runoff passes through a silt trap or settling chamber before entering the borewell, preventing clogging.

- The design includes safety features such as protective grills and annual disinfection. Routine maintenance—particularly desilting before each monsoon and cleaning the filter media every two to three years—ensures optimal performance.

Proven Models of Success: Case Studies

- Gujarat: In Navagam village, Panchmahal district, ICAR-IISWC’s installation of runoff filters (2017–20) increased the average groundwater table by 1.84 metres.

- The improved availability expanded the irrigated area by 12 hectares and enhanced crop yields—cotton productivity rose by 0.8 tonnes per hectare, and maize by 0.6 tonnes per hectare.

- Farmers’ incomes increased by ₹16,000 per hectare, with return-to-cost ratios ranging between 1.65 and 2.89.

- Karnataka: In Maramannahali village, Chitradurga district, a farmer transformed a low-yielding borewell into a recharge system and adopted drip irrigation.

- Annual income jumped from ₹53,500 in 2016–17 to ₹1.75 lakh in 2020–21, because of improved water availability and cultivation of high-yielding tomato and chilli varieties.

Blueprint for Punjab’s Water Future

- Punjab has the unique opportunity to turn a liability into a lifeline, with 1.4 million unused borewells. Large-scale conversion of abandoned borewells into recharge units could help:

- Absorb floodwaters during heavy monsoons, reducing surface runoff.

- Replenish depleted aquifers, supporting long-term water security.

- Lower public spending on flood infrastructure and groundwater extraction.

- Enhance agricultural resilience by stabilizing irrigation sources.

- If implemented through village-level programs, with technical support from ICAR-IISWC and state agencies, this approach could redefine climate adaptation in the Punjab plains—turning every abandoned borewell into a portal of renewal.

Mission Food, Fodder, and Water (FFW) Project

Context

- Kerala's forest department plants fruit and fodder trees to ease human-wildlife tensions.

About the Mission Food, Fodder, and Water (FFW) Project

- It is envisioned as a multi-sectoral rural resilience initiative launched to address three interconnected crises—food insecurity, fodder scarcity, and water stress.

- It builds upon the Jal Shakti Abhiyan (2019), National Fodder Mission (2012–2018), and National Food Security Mission (NFSM), integrating their outcomes under a single operational vision of climate-adaptive resource management.

Key Objectives

- Ensure Ecological Balance: Replenish natural food and water sources within forests and buffer zones.

- Prevent Human-Wildlife Encroachment: Reduce crop raiding, livestock attacks, and resource competition.

- Promote Coexistence: Support local communities through compensation and sustainable livelihood programs.

- Restore Forest Ecology: Improve degraded forest patches to sustain native herbivores.

Components of the Mission

- Food Security Component: Promotion of climate-resilient crops (millets, pulses, and oilseeds).

- Introduction of biofertilizers and micro-irrigation to boost yields.

- Integration of kitchen gardens and nutri-gardens in rural schools and Anganwadis.

- Fodder Security Component: Expansion of fodder banks and silage units under cooperative models.

- Revival of common grazing lands through reseeding and rotational grazing.

- Linking livestock missions with dairy productivity and veterinary care.

- Water Conservation Component: Construction of check dams, farm ponds, and percolation tanks.

- Revival of traditional water bodies like baolis, talabs, and johads.

- Emphasis on rainwater harvesting and aquifer recharge through community labour.

Policy Linkages

- United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation), SDG 13 (Climate Action), and SDG 15 (Life on Land).

- India’s National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC)—specifically the National Mission for Sustainable Agriculture (NMSA) and National Water Mission (NWM).

Iceland Declares AMOC Collapse a National Security Threat

Context

- Recently, Iceland declared the potential collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) as a direct threat to its national security and existence.

About Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC)

- It is a large system of ocean currents that transports warm, salty water from the tropics northward and returns cooler, deeper water southward, often referred to as the ‘climate engine’ of the Atlantic Ocean.

- It governs the movement of warm and cold water across vast oceanic distances, influencing weather patterns, sea levels, and global temperatures.

- It is driven by differences in temperature (thermal) and salinity (haline) — hence the term thermohaline circulation.

- The most well-known component of the AMOC is the Gulf Stream, which carries warm water from the Gulf of Mexico across the North Atlantic toward Europe.

Why does the AMOC Matter?

- Regulate regional temperatures, particularly keeping northern Europe’s climate milder.

- Distribute ocean nutrients, supporting marine ecosystems and fisheries.

- Stabilize weather patterns, reducing the frequency of extreme events.

- Control sea levels, especially along the eastern coast of North America.

Signs of Weakening

- In recent decades, scientists have observed signs that the AMOC is slowing down. Key indicators include:

- Accelerating Greenland ice melt, which adds freshwater to the North Atlantic and disrupts salinity.

- Rising ocean temperatures, which alter density gradients and reduce water sinking.

- Shifts in Atlantic sea-surface patterns, observed through satellite and ocean buoy data.

- A study in Nature Climate Change (2021) suggested that the AMOC is now at its weakest point in over a millennium, signaling a potential tipping point.

Consequences of an AMOC Collapse

- A complete or partial collapse of the AMOC could trigger severe and irreversible climate changes, including:

- Harsher winters and shorter growing seasons in Europe.

- Rising sea levels along the U.S. East Coast due to redistribution of ocean mass.

- Disruption of monsoon systems, affecting billions of people in Africa and Asia.

- Shifts in marine biodiversity and collapse of key fisheries.

- These cascading impacts could destabilize economies, ecosystems, and even geopolitical relations.

Mount Semeru Erupts Again

Context

- Indonesia’s Mount Semeru, the country’s highest volcano at 3,676 metres, erupted 10 times recently, forcing emergency evacuations of over 1,000 residents, including 170 stranded climbers.

About Semeru’s Volatile History

- Mount Semeru, located in East Java, is part of the Pacific Ring of Fire, a seismically active belt known for frequent earthquakes and volcanic eruptions.

- Indonesia hosts over 120 active volcanoes, making it one of the most volcanically active regions globally.

- The climate patterns like La Niña often exacerbate volcanic risks in Indonesia by increasing rainfall, heightening the likelihood of secondary disasters such as lahars and landslides.

Environmental Consequences

- Ash emissions from Semeru’s plume are expected to influence local air quality and climate patterns in the short term.

- Fine ash particles can contaminate water sources and damage crops, posing challenges for local farmers.

Expansion of PMFBY From 2026

Context

- Recently, the Government has announced a significant expansion of the Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY).

About the PMFBY Expansion

- Crop losses due to wild animal attacks aim to be covered as a localised risk, and inundation of paddy due to rainfall and waterlogging starting from the 2026 Kharif season — which was excluded in 2018 — has been reinstated.

Addressing Long-Standing Farmer Concerns

- Farmers from states such as Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, and Chhattisgarh have consistently raised concerns over crop damage by wild animals like nilgai, wild boars, and elephants, which have led to substantial economic losses.

- However, such damages were not previously covered under PMFBY, leaving affected farmers without any financial safety net.

- The inclusion of wild animal attacks as a compensable risk under the scheme reflects the government’s recognition of this growing human-wildlife conflict issue, especially in forest-fringe and rainfed regions.

Reinstating Paddy Inundation Coverage

- The inundation of paddy fields due to excessive rainfall or waterlogging was removed from the PMFBY coverage in 2018 to streamline claims and reduce insurer liabilities.

- However, recent years have seen increasing instances of flash floods and unseasonal rains—particularly in eastern India—leading to massive paddy crop destruction.

- States like Bihar, Assam, and West Bengal, paddy farmers frequently face losses from waterlogging, with limited recovery mechanisms.

- The reinstatement of this clause is expected to provide much-needed financial relief and stability to millions of small and marginal farmers.

Himalayan Black Bears

Context

- Recently, the Uttarakhand Forest Department issued the state’s first-ever shoot-at-sight orders for Himalayan black bears, following a surge of violent encounters.

About Himalayan Black Bears (Ursus Thibetanus Laniger)

- These are a subspecies of the Asiatic black bear, facing increasing threats from climate change, habitat loss, and human-wildlife conflict.

- IUCN Status: Vulnerable (as part of the broader Asiatic black bear species)

- WPA 1972 Status: Schedule I

- Habitat: Found in the Himalayan regions of India, Nepal, Bhutan, and parts of China and Pakistan, typically inhabiting temperate broadleaf forests and alpine scrub zones between 1,200–3,300 meters.

Conservation Concerns

- Climate Change Disruption: Rising temperatures are altering the bears’ natural hibernation cycles.

- In Uttarakhand, India, warmer winters have led to bears remaining active year-round, increasing the likelihood of human encounters.

- Human-Wildlife Conflict: In 2025, Uttarakhand reported 71 black bear attacks in just three months, resulting in six human deaths and the loss of 60 livestock.

- It led to controversial shoot-at-sight orders in Pauri district.

- Habitat Fragmentation: Expanding human settlements, deforestation, and infrastructure development are shrinking the bears’ natural range, forcing them into closer proximity with people.

Conservation Measures

- Protected Areas: Many populations reside within national parks and wildlife sanctuaries, such as Dachigam National Park (Jammu & Kashmir) and Great Himalayan National Park (Himachal Pradesh).

- Community Engagement: Conservationists advocate for coexistence strategies, including awareness campaigns, compensation for livestock loss, and bear-proof waste management in villages.

‘Brain Fever’ Cases in Kerala and Karnataka

Context

- Recently, the Health departments in Kerala and Karnataka issued urgent public advisories, following a sudden rise in cases of amoebic meningoencephalitis (AME)—a rare but deadly brain infection often dubbed ‘brain fever’.

About the Amoebic Meningoencephalitis (Brain Fever)

- Amoebic meningoencephalitis is caused by Naegleria fowleri, a free-living amoeba found in warm freshwater sources like ponds, lakes, and rivers.

- The amoeba enters the human body through the nasal passage when contaminated water is inhaled, typically during bathing or swimming.

- Once in the brain, it destroys brain tissue, causing swelling and inflammation.

- Symptoms usually appear within 1–12 days and include severe headache, high fever, nausea and vomiting, stiff neck, confusion, seizures, or hallucinations.

- The disease progresses rapidly and is almost always fatal if not detected early.

Red Sanders Export Quota

Context

- Recently, the Directorate General of Foreign Trade (DGFT) raised India’s export quota of red sanders (Pterocarpus santalinus) from 1,180 tonnes to 1,290 tonnes, effective until March 31, 2027.

About Red Sanders

- Red sanders is a highly valued hardwood species native to the Eastern Ghats of southern India.

- Its rich red hue makes it prized for luxury furniture, musical instruments, and natural dyes.

- Red sanders has faced decades of illegal logging and smuggling, especially from Andhra Pradesh’s Seshachalam Hills.

- The wood’s high demand in East Asian markets — particularly China and Japan — has fueled a black market trade worth hundreds of crores.

- MoEFCC, in 2019, reiterated that only legally sourced and certified stock could be exported, typically from government-seized or naturally fallen trees.

- IUCN Red List: ‘Endangered’

- CITES: Appendix II

Recalling Vanashakti Judgement of Supreme Court

Context

- Recently, a three-judge bench of the Supreme Court has recalled its May 2025 ruling, popularly known as the Vanashakti Judgement, emphasizing the sanctity of the ‘prior environmental clearance’ process under the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986, declaring post-facto approvals legally untenable.

Background of the Vanashakti Judgment

- The Vanashakti judgment originated from a series of writ petitions filed by the environmental NGO Vanashakti against the Union of India, challenging the legality of granting post-facto environmental clearances.

- It means approvals granted after a project has already commenced operations without prior environmental clearance.

- In its original ruling, the Supreme Court had barred the practice of post-facto clearances, emphasizing that such approvals defeat the purpose of environmental laws and undermine the EIA process.

- The judgment was seen as a significant step toward strengthening environmental accountability and upholding the precautionary principle.

Implications and Reactions

- Environmental Concerns: The recall weakens environmental safeguards and sets a dangerous precedent by allowing violators to regularize illegal projects retroactively.

- Legal Debate: The case has reignited discussions about the separation of powers between the judiciary and the executive, and the role of courts in enforcing environmental norms.

- Policy Uncertainty: The reversal may create ambiguity in environmental regulation enforcement, potentially emboldening non-compliance among industrial actors.

Framing Uniform National Organ Transplant Policy

Context

- Recently, the Supreme Court of India has directed the Union Government to formulate a uniform national policy for organ transplantation and emphasized the need for a centralized mechanism to oversee ethical, transparent, and equitable distribution of organs across the country.

Court’s Directives

- The Centre to create a national-level regulatory framework for organ procurement and distribution.

- All states and Union Territories to establish state-level agencies aligned with the national framework.

- Uniform laws and procedures for organ donation, registration, and transplant approval to prevent regional disparities.

Need for a Uniform Policy

- Currently, organ transplantation in India operates under the Transplantation of Human Organs and Tissues Act (THOTA), 1994, but its implementation varies across states.

- It has led to fragmented registries, bureaucratic hurdles, and inequitable access—particularly for economically weaker patients and those in rural areas.

- The Supreme Court observed that while states like Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, and Kerala have well-established systems, other regions lag due to inadequate infrastructure and coordination.

Data and Concerns Highlighted

- India faces a severe organ shortage: only about 10,000 kidneys and 1,000 livers are transplanted annually against a demand of nearly 2 lakh.

- The cadaveric donation rate remains under 0.5 per million population, among the lowest globally.

- Lack of awareness, misinformation, and poor hospital coordination hinder donation rates.

- A centralized waitlist system like that of the U.S. (UNOS) is absent, leading to uneven organ allocation.

Towards a Transparent National System

- Integration of the National Organ and Tissue Transplant Organisation (NOTTO) with regional and state networks.

- Mandatory digital tracking systems for donor and recipient matching.

- Public awareness campaigns to boost voluntary organ donation.

- Collaboration between public and private hospitals under common ethical standards.

Way Forward

- The Supreme Court’s intervention is expected to pave the way for a cohesive national framework—ensuring organs are distributed based on medical urgency, not geography or privilege.

- A truly national approach must blend policy reform, technology, and ethical oversight to build public trust and save countless lives.

Kendu Leaf Dispute in Odisha

Context

- A recent dispute over the trade and transport of kendu leaves in Odisha has reignited debates over the interpretation and implementation of the Forest Rights Act (FRA), 2006.

- It underscores the persistent tension between the state forest department’s monopoly and the forest-dwelling communities’ rights to manage and sell minor forest produce (MFPs).

Core of the Dispute

- At the heart of the dispute lies the Odisha Kendu Leaves (Control of Trade) Act, 1961, which vests exclusive trading rights in the state government.

- Under this law, the Odisha Forest Development Corporation (OFDC) controls collection, processing, and sale of kendu leaves — a high-value non-timber forest product used in bidi (traditional cigarette) manufacturing.

- However, Gram Sabhas and tribal cooperatives in several districts have accused the state of violating the community forest resource (CFR) rights guaranteed under the FRA.

- These communities argue that the monopoly of OFDC negates their economic autonomy and contravenes Section 3(1)(c) of the FRA, which recognizes the right of forest dwellers to own, use, and dispose of minor forest produce.

Socioeconomic Stakes

- Kendu leaves represent a crucial livelihood source for over 800,000 tribal families in Odisha.

- Studies demonstrate that kendu leaf collection contributes up to 40–60% of annual income in forest-dependent villages during the lean agricultural season.

- The delayed payments and low procurement rates fixed by OFDC have worsened economic distress.

- By contrast, in states like Chhattisgarh and Maharashtra, where Gram Sabhas directly manage kendu leaf trade post-FRA, income levels have improved significantly.

State vs. Community

- State Position: The Odisha Forest Department argues that centralized trade ensures quality control, worker safety, and stable revenue for welfare schemes.

- Community Perspective: Tribal federations, argue this structure undermines local self-governance.

- They contend that Gram Sabhas, not state corporations, should decide trade modalities as per FRA guidelines.

- It has led to protests and legal petitions, with communities demanding repeal of the 1961 Act or its alignment with FRA provisions.

Policy Gaps and the Way Forward

- Devolution of trade rights to Gram Sabhas through state notifications.

- Transparent price fixation and decentralized procurement mechanisms.

- Abolition or amendment of the Odisha Kendu Leaves (Control of Trade) Act, 1961.

- Creation of joint forest management committees integrating traditional institutions.

Cystic Fibrosis (CF)

Context

- Cystic Fibrosis (CF) has long symbolized the gap between medical innovation and accessibility.

- While treatments like Trikafta revolutionized patient outcomes, their staggering cost — around US $325,300 per patient per year — placed them beyond the reach of most.

About Cystic Fibrosis (CF)

- It is a rare genetic disorder caused by mutations in the CFTR gene, leading to thick mucus buildup in lungs, pancreas, and other organs. It severely impacts respiratory and digestive systems.

- Approximately 162,000–188,000 people live with CF across 94 countries, though only 12% currently receive triple combination therapy due to affordability issues.

- The condition is more prevalent in Western populations but is increasingly being recognized in India due to better genetic and clinical awareness.

- The price barrier is catastrophic — particularly given that CF life expectancy remains under 20 years without proper treatment for low and middle income nations.

Why Bangladesh?

- Bangladesh, as a Least Developed Country (LDC), remains exempt from the WTO’s TRIPS (Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights) agreement until 2026.

- It allows Bangladeshi firms to legally produce patented drugs for domestic and export use to other LDCs, bypassing expensive licensing restrictions.

- Bangladesh exports to 150+ countries, including several in Europe and North America, producing 97% of its own drug requirements.

- It remains the only LDC to fully capitalize on TRIPS flexibilities to develop a globally competitive pharma ecosystem — one marked by stringent regulatory oversight, efficient manufacturing, and ethical marketing practices.

Why Not India?

- India, long dubbed the ‘pharmacy of the world’, might seem the natural partner for such a venture.

- But its adherence to TRIPS and its complex, fragmented regulatory framework limit flexibility.

- Indian manufacturers often depend on voluntary licensing from multinational corporations — arrangements that favor the patent-holders and restrict geographic reach.

- Furthermore, India’s credibility has been dented by recent safety scandals, including toxic cough syrups linked to child deaths in The Gambia, Uzbekistan, and within India itself — attributes to ‘regulatory chaos’ and lack of coordination between central and state drug authorities.

- By contrast, Bangladesh’s centralized and disciplined regulatory structure offers a model of order and compliance, balancing innovation with public health priorities.

Subjective Questions for Practise

Q1. Examine the key provisions of India’s Draft Seeds Bill, 2025. How does the Bill aim to balance the interests of farmers, seed companies, and the government, and what challenges might arise in its implementation?

Q2. Discuss the global rise in the consumption of ultra-processed foods and evaluate the associated health, economic, and environmental risks.

Q3. Evaluate the environmental sustainability of India’s rapidly expanding data centre industry, with a focus on its hidden water consumption. How can India balance digital infrastructure growth with its looming water crisis?

QUICK LINKS